Continuing a series that celebrates the fifty-fifth anniversary of Night of the Living Dead with a look at the classic zombie film and its many follow-ups.

Any film will have a few production oversights, in the case of Night of the Living Dead, a small error had a major impact. The original title Night of the Flesh Eaters was scrapped on the grounds that it had been taken by another film, and so the crew prepared a new title card for the renamed Night of the Living Dead. In this hasty switch, they also inadvertently removed all of the copyright information from the film’s print. Upon release, Night of the Living Dead went immediately into the public domain: anyone could release a copy, and the actual creators saw the merest fraction of its revenue.

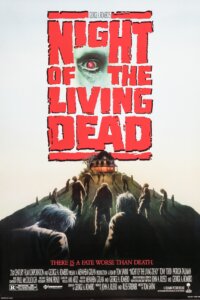

Still smarting from this screw-up decades down the line, George A. Romero and his sometime collaborators John Russo and Russell Streiner came up with a way of rectifying matters: by making Night of the Living Dead again. The remake came out in 1990, scripted by Romero with Russo and Streiner producing. That the new film was an effort to reclaim what had been lost through the 1968 copyright oversight is no secret, being established in the “making-of” featurette on the remake’s DVD release.

While no film remake is entirely necessary, and this remake is a particularly clear product of profit-driven rather than creative concerns, Romero also had aesthetic reasons for their interest in a second try at Night of the Living Dead. Viewed as part of a trilogy with Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead, Night was clearly the odd-one-out, with its black-and-white cinematography, fresh-faced zombies and lack of Tom Savini gore effects. There is, after all, a reason why Dawn, rather than Night, became regarded as the fountainhead of splatter cinema.

With their remake, Romero and company had the chance to put together a Night of the Living Dead that truly belonged to the Savini era of horror cinema – indeed, Savini ended up directing the project, making his debut as a feature director (he had previously helmed some episodes of the TV series Tales from the Darkside). If the original Night of the Living Dead marked the end of the Famous Monsters of Filmland era, this remake could be tailor-made for the Fangoria generation.

Alas, the project did not go smoothly for Savini. In a 2004 interview with Film Monthly, he spoke about the trouble he ran into from both censors and producers (although he was discrete enough to avoid specifying which of the multiple producers gave him grief):

It was the worst nightmare of my life. […] My problem with the remake and the reason I call it a nightmare is because, you know, I had lots of ideas. I had some eight hundred story boards and the whole movie was actually shot on paper. See, George Romero wasn’t there. George was off in Florida writing The Dark Half. I got stuck with these two idiot producers that didn’t know anything and their careers prove it and, you know, I didn’t want to make their bad movie for them. You know my hands were just slapped all over the place. I couldn’t do a lot of stuff. The movie is about forty percent of what I intended. It would be a much better movie if I had got to put in all the stuff I really wanted to do. Then the MPAA hit us hard.

Savini’s version of events is easy to believe, as the Night of the Living Dead remake has many of the symptoms that come with a confused creative process. Watching the film’s early stretches is akin to being stuck in a pub with a drunkard trying and failing to recite a familiar anecdote: it hits the beats from the original, yet gets into a complete muddle.

Once again, we start with siblings Barbara and Johnny arriving at a graveyard, where Johnny points to a passer-by while teasing Barbara. But this time, the passer-by is not a zombie; instead, he appears to be a confused old man with some sort of head injury (his presence is never fully explained). Only after this bizarre twist does a real zombie lunge out to attack Johnny. It is hard to argue that Romero and Russo’s iconic opening is in any way improved by these changes.

Despite such early stumbles, the film becomes more watchable when the plot progresses, although some of this is little more than the Pavlovian appeal of seeing familiar elements fall into place. One by one, characters from the original film turn up to join Barbara – Ben, Tom, Judy, the Coopers – and, although recast, have generally changed little since 1968. While there were opportunities to shake up the characters and their arcs (what if it were the little girl Karen rather than Barbara who fled the graveyard at the start? What if Ben, rather than Mr. Cooper, had a wife and child?) these are largely ignored.

With one major exception.

Played by Patricia Tallman, the Barbara of 1990 is a completely different character from the traumatised, passive Barbara of 1968. With her short hair, tank top and shotgun, she is tailored to an audience that had come to accept women-of-action like Ellen Ripely in the Alien films, a character type that barely existed when the original Night of the Living Dead was made. She is allowed to alternate with Ben as the sensible one of the group; and while Ben and Mr. Cooper argue about whether upstairs or downstairs are the best hiding places, it is Barbara who points out that heading outside, past the slow-moving zombies, is also a viable option.

The knock-on effects of Barbara’s new persona can be seen across a few other members of the cast. Judy, never a particularly well-defined character, is given Barbara’s old role of screaming in panic; she is also established as a member of the family that owned the farmhouse, giving her the additional trauma of seeing her zombified neighbours gunned down. To suit the new gun-toting heroine, Mr. Cooper’s role as violent antagonist is elevated; regrettably, his new material comes at the expense of his daughter, whose name has oddly been changed from Karen to Sarah. The harrowing scene of the little girl killing her own mother is wasted, being moved to an earlier point in the narrative and thereby drained of its impact.

Like its protagonist, the Night of the Living Dead remake pulls itself together as it goes along, and aside from the occasional relapse succeeds in shaking off its early confusion. While there is room to question whether our action heroine benefits from being inserted into the plot of Night of the Living Dead, “Ripley versus the zombies” is a fetching premise, perhaps even a necessary one during the rise of third-wave feminism.

The remake’s Barbara could never suffer the fate of her sixties counterpart, left helpless while zombies swarm in through the door. In the script’s single biggest deviation from the original film, she makes it out of the house and ends up with a zombie-hunting militia. The next morning, Barbara looks on at the disturbing sight of hooting and hollering gunmen using lynched zombies as target practice. “They’re us,” she remarks. “We’re them and they’re us.” This is a Night of the Living Dead that truly feels like a prequel to Dawn of the Dead.

It has to be admitted that the remake has not aged particularly well. The 1968 original, both groundbreaking and a monochrome throwback, is timeless; the 1990 version is a relic of its period. At the same time, however, the updated Night of the Living Dead could have been much worse.

As if to illustrate this point, “much worse” was embodied by a film that came out the following year: Night of the Day of the Dawn of the Son of the Bride of the Return of the Revenge of the Terror of the Attack of the Evil, Mutant, Alien, Flesh Eating, Hellbound, Zombified Living Dead Part 2: In Shocking 2-D. This was the project of James Riffel (working under the pseudonym Lowell Mason) and, like the remake, owed its existence to the original film’s public domain status. With no issues of copyright to face, Riffel was able to take Night of the Living Dead and add his own comedy voiceover, creating a feature-length parody on a shoestring.

As the director explained when interviewed for Mark White’s book Mad Movies with the LA Connection, the film grew out of an unreleased student project (hence the “Part 2” in the title) but took on a life of its own:

As a joke, I ended up listing the forty-five-word title in Variety’s ‘Films in Production’ section. It immediately received major publicity solely based on the title. Radio DJs were talking about it, it appeared in the New York Times film section, it was mentioned on MTV and someone even told me that Johnny Carson mentioned it on The Tonight Show. […] I made the original version in 1991 and distributed it myself through Palmer Video – a chain of roughly one hundred video stores based in New Jersey – and other ‘mom and pop’ shops across the U.S. I made 500 copies.

Mystery Science Theater 3000 – which had started shortly beforehand, in 1988 – used the same basic premise as this gag movie, and found cult success. But Mystery Science Theater always knew how to vary its format: replacement dialogue of the sort seen in Night of the Day of the Dawn was only one item in the repertoire.

James Riffel’s take on Night of the Living Dead wears out its welcome about twenty-five minutes in. It relies heavily on obvious stereotypes; the Graveyard Ghoul is characterised as a camp gay man, Ben becomes a jive-talker who spontaneously devises rap lyrics, Tom is a surfer-dude and so on. (Mr. Cooper, now a KKK member with a fetish for women’s underwear, is at least given two stereotypical traits to work with, which is more than most of the cast).

There are some running gags that had potential, like the notion that the zombies are created by overwork at 9-5 jobs or Mrs. Cooper being repeatedly reminded of when and how she will die, but these are swamped by ironic racism and detailed descriptions of bowel movements. Night of the Living Bread, a 1990 student film by Kevin S. O’Brien, is based around a single joke but nonetheless packs more wit into its eight-minute runtime than Night of the Day of the Dawn manages in an hour and a half.

While both the official and unofficial Night of the Living Dead reworkings are now dated, they retain some shared interest as evidence of the original film’s dual identity. On the one hand, it stands as the starting point of a franchise personally overseen by one of horror’s greatest auteurs, George A. Romero. On the other, Night of the Living Dead is a public-domain cultural artifact that belongs to the world. In theory, for better or worse, anyone can make their own Night of the Living Dead.

Next: Splatterpunks not dead…