“I’m a feminist, I get angry, but I think humour’s a great weapon. I like using humour to say things.”

—Joanna Quinn

Joanna Quinn was an avid cartoonist from an early age: when she was just 14 years old she took her portfolio to Britain’s premiere comic, The Beano. Although the powers that be did not give her a job, they did send her off with the valuable advice to study at art school. And so she enrolled first at Goldsmiths College and later at Middlesex Polytechnic, where she dabbled in photography, life drawing, and animation.

Although she tried out traditional cartoon animation with a short called Superdog (later described by Clare Kitson, in her book British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor, as being “extraordinarily accomplished for a beginner”) Quinn would find her calling when she tried mixing animation with the technique of life drawing.

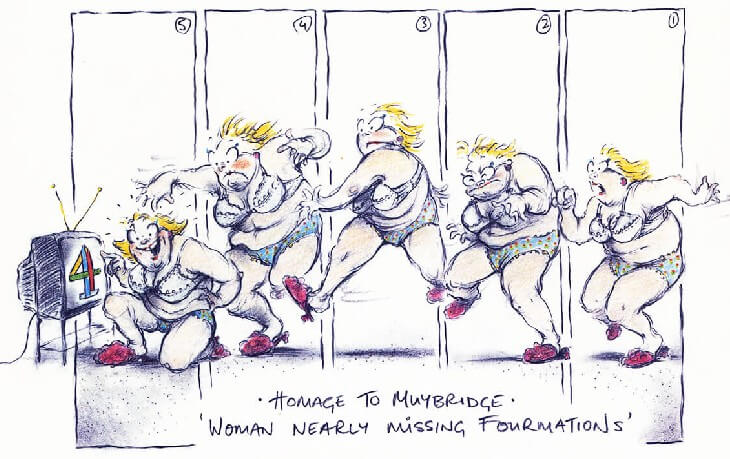

The combination was evident in Quinn’s final film as a student, Girls Night Out, which remained incomplete at the time of her graduation in 1985, but by all accounts remained an impressive piece of work. After moving to Wales, she was able to persuade both the Welsh channel S4C and England’s Channel 4 to fund the completion of Girls Night Out as a professional short.

The film tells the comedic tale of a factory worker named Beryl who escapes from her apathetic husband on her birthday to attend a pub party. There, she and her friends gawp at a male stripper, and she ends up taking his leopard-print thong home with her. The final scene has Beryl hanging the thong on a coat-rack like a trophy while her oblivious husband continues to scowl at the television.

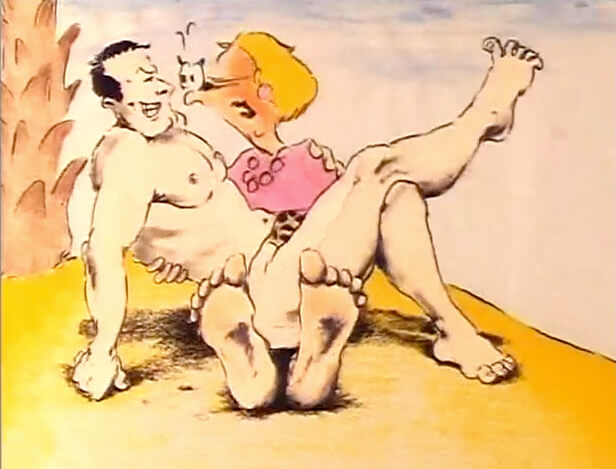

Girls Night Out is, in part, a love-letter to animation conventions: throughout the short, Quinn appears to be running through a checklist of familiar cartoon iconography. In the scene that establishes Beryl’s sexual frustration, her fantasies are portrayed using a traditional thought-balloon over her head; inside is a desert island (with a single palm tree, naturally) where a smooth-talking Tarzan engages her in furious love-making – depicted using the kind of dust-cloud typically associated with fight scenes. The climax with the stripper, meanwhile, has obvious similarities to Tex Avery’s classic short Red Hot Riding Hood, in which a male wolf watches a sexualised Little Red Riding Hood performing on stage.

However, at the same time, Quinn turns conventions on their head by using an unapologetically female perspective. The male gaze is conspicuously absent, with dumpy, bespectacled Beryl a world away from such prettified heroines as Betty Boop and Minnie Mouse. Her most obvious predecessor is Flo, the long-suffering housewife from Reg Smythe’s comic strip Andy Capp; but instead of being the straight-partner in the story of a drunken wife-beater, Beryl is the star of her cartoon and the character the audience is expected to relate to.

Beryl’s appeal as a character can, perhaps, be attributed to the fact that she was drawn from life, being modeled off of two women known by Quinn. One was a canteen lady who worked at Middlesex Polytechnic during the film’s conception and served as Beryl’s original voice actress (she was later replaced in the finished film by professional actress Myfanwy Talog.) The other model was Quinn’s mother, a single parent who “was always struggling to pay the bills, but always laughing,” according to her daughter.

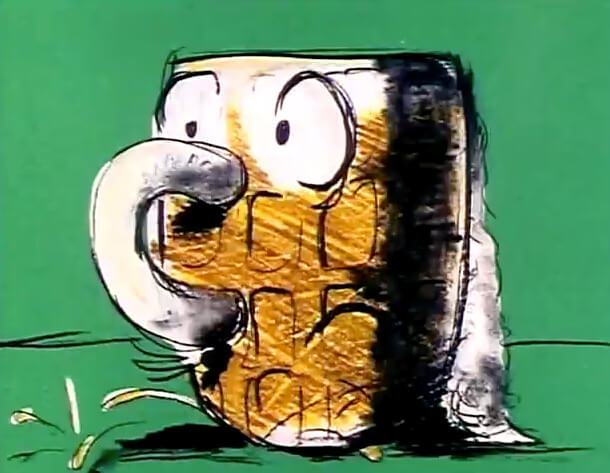

Quinn’s use of gender role-reversal is most evident in the sequence with the stripper. Many cartoons have shown male characters gawping at sexualised women, but Quinn portrays a sexualised man being leered at by a roomful of women. One of the many sight gags has a tankard of beer suddenly sprout eyes as it stares at the stripper; while this kind of anthropomorphism is commonplace in cartoons, Quinn adds a twist by avoiding conventional gendered iconography. As the tankard is watching a male stripper, the audience can infer that the tankard character is female; yet it lacks eyelashes or any other standard cartoon shorthand for femininity. Instead, it is shown “sweating” foam in what can be read as a female counterpart to the familiar gag of the erection take, where the entire body of a male character stiffens during arousal.

The film demonstrates Quinn’s joint interests in animation and life drawing. Although the characters are made up of loose, broad strokes of the pencil, the strength of their underlying forms is clear. When those forms start distorting for comic effect, the results are all the more striking.

Prior to being aired on Channel 4 in 1988, the film was screened at the 1987 Annecy International Animation Film Festival, where it won three prizes. Visiting animation festivals was something of a mixed experience for Quinn, as she discussed when interviewed for Jayne Pilling’s 1992 book Women & Animation. “It’s as if time hasn’t really moved on for a lot of these men; there’s that old school of sexist jokes about women’s bodies,” she said. “I think women’s films tend to be more personal… seeing women’s animation at festivals – it’s a lot fresher.”

While Girls Night Out was being completed, Quinn teamed up with Les Mills – who had helped with the sound on her short – to form Beryl Productions. In 1990,Beryl Productions released a sequel to Girls Night Out, animated by Quinn and written by Mills: Body Beautiful.

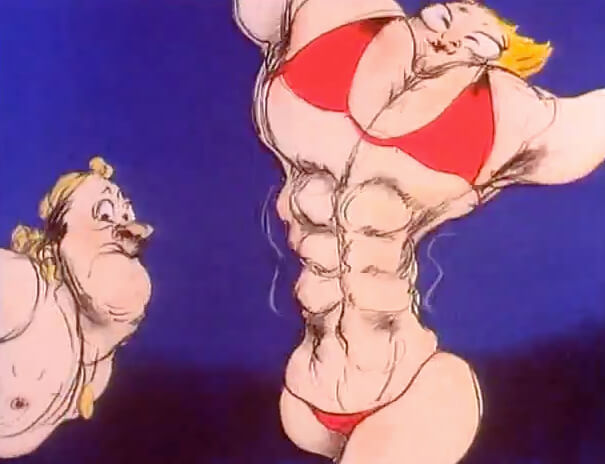

Body Beautiful gives Beryl an antagonist in factory co-worker Vince. A caricature of macho masculinity – hairy chest, medallion, blonde bubble-perm mullet – Vince brags about his sexual desirability and openly mocks Beryl for her weight. Beryl tries to slim down by dieting, but ends up eating junk food on the sly; she then begins a fitness regimen, only to find that it has no discernible effect on her appearance.

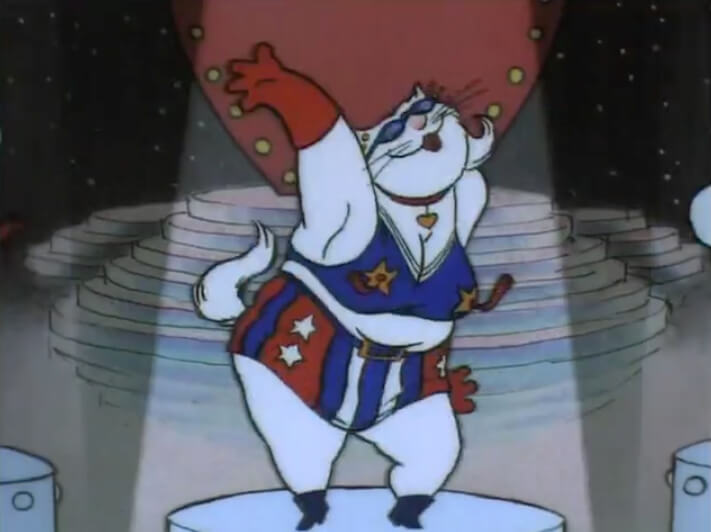

The climax takes place in a “body beautiful” contest held by the factory, with the staff showing off their figures. Beryl’s female co-workers perform a ballet, while Vince and the other men flex their muscles on stage (shades of the male stripper from Girls Night Out). Finally, the contest receives a surprise last-minute entrant – Beryl. Striding on stage in a bikini, Beryl performs a rap about her newly-developed self-esteem. The whole audience – including Beryl’s grumpy husband – is impressed, and Vince slinks away in shame as she is pronounced the winner.

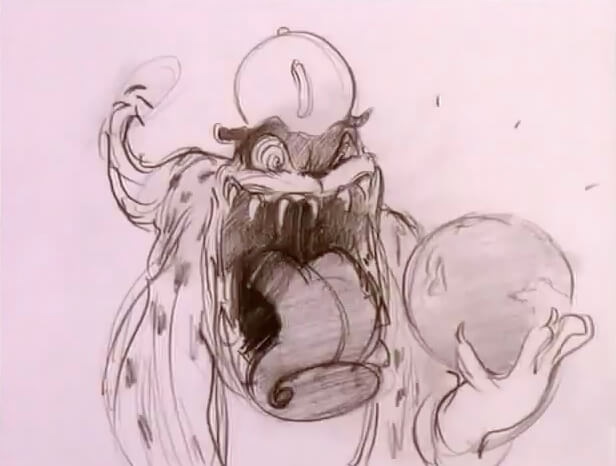

Body Beautiful takes the cartoonish distortions of Girls Night Out to a whole new level, with Beryl’s on-stage battle against Vince containing as many bodily transformations as a typical fight between Popeye and Bluto. The portly heroine stretches, morphs, and literally yanks the smile off Vince’s face; she changes into a slim, shapely woman, and also into a hulk of muscle – at which point her abs turn into honking trumpets.

Quinn certainly had a strong character on her hands with Beryl, who had the potential to become feminist animation’s answer to Homer Simpson. A television series was an obvious next step, but Quinn was reluctant to explore this avenue. “There’s a bit of interest in doing a Beryl [TV] series”, she told Pilling. “She’d be an obvious choice because she’s such a good character and you could really build something around her. But I have a slight fear that once that happens it’s ‘Bye Beryl’ – I’ll lose her. She’ll end up all horrible… banana fingers with stripes on… Mickey Mouse hands done by loads of inbetweeners.”

Didier Brunner, a French film producer later involved with such classics of Gallic animation as Triplets of Belleville and Kirikou and the Sorceress, noticed Quinn’s work and hired her to work on a project entitled Cabarets. This was a series of short films, made by animators from across Europe, celebrating the work of painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and screened as part of a 1992 exhibition. Quinn’s short was Elles, which takes its inspiration from a series of pictures showing brothel workers made by Toulouse-Lautrec circa 1896 – particularly “The Sofa,” depicting a lesbian couple. Quinn has fun imagining what may have gone on behind the scenes: when the artist is out of the room, the two models dance, feast and smooch, before rushing back into their poses as they hear his footsteps approaching.

With her next film, Britannia (1993), Quinn mixed cartoon slapstick with sharp satire of British imperialism. The short opens with a bulldog, somewhat resembling Spike from the Tom & Jerry cartoons, waking up to find itself astride a map of Britain. The upper-class accent of its owner (identified in the credits as Britannia, Britain’s traditional personification) chirps orders from offscreen. Following the commands of its mistress, the bulldog claws at Scotland and Wales before nailing a Union Jack over Ireland.

The world suddenly shrinks, and the bulldog is left playing not only with the United Kingdom but with the entire globe. Meanwhile, its unseen owner ceases to give orders, leaving the dog master of its new domain. It treats the globe as a chew-toy and stares in bewilderment as tiny people scurry away in fear. Continuing to play around, the dog pulls a set of objects out of the globe: first, a teapot, which it wears as an absurd crown; then the regal robe of a king, which it yanks out from a pair of Indian women; next, a heap of coins that it pours straight into its mouth. Along the way, the dog transforms into a series of caricatures: an oligarch with a pound coin for a monocle; a bishop holding a globe spiked with crosses; Queen Victoria.

The bulldog, once a gormless mutt, takes on an increasingly demonic appearance as it continues to plunder the globe; in turn, the cartoon’s acerbic humour becomes thoroughly macabre. The giant dog reaches into a peaceful African village and lifts out the residents in a string, before wearing them as a necklace. One of the people tries to flee, only to be impaled and eaten by the dog.

Then the tiny globe suddenly grows, while the bulldog shrinks down into a small, prettified Shih Tzu. For the first time, we see the dog’s owner: not mighty Britannia, but a nondescript woman in a skirt and blouse. The final scene has the owner taking the tiny dog on a walk through a modern, multi-cultural Britain, both characters disappearing into a crowd of Black and Asian passers-by. The end credits are accompanied by a rousing rendition of “Rule Britannia,” which ends up as a discordant approximation of the Looney Tunes theme. That’s all, folks!

Quinn’s career then moved in a more mainstream direction. Producer John Coates, who had been involved with Channel 4’s successful adaptations of picture books by Raymond Briggs, hired her to direct a 1996 half-hour family special. Entitled Famous Fred, the film was again adapted from a picture book: Fred, by Posy Simmonds.

It was a good match. Simmonds was an early influence on Quinn’s work, and it is hard to miss the common ground in their approaches. They each balance the painterly with the cartoonish, and show delight in capturing the smaller details of everyday settings and people. In her Women & Animation interview, Quinn praises Simmonds’ work: “it’s not feminist in that brow-beating way. I’m a feminist, I get angry, but I think humour’s a great weapon. I like using humour to say things.” That said, feminism is not a particularly noticeable theme in Famous Fred, the tale of a larger-than-life male character.

The story begins with two children mourning the death of their cat, Fred. Sneaking out into the garden one night, they find an array of well-dressed cats holding a funeral for the departed pet. It turns out that Fred was not, as the children believed, “the laziest cat in the world.” He was actually the feline equivalent of Elvis, and entertained countless fans by performing rock numbers from atop the fence. The film’s voice cast is an interesting range of talent, with comedian Lenny Henry voicing Fred, respected stage actor Tom Courteney playing Fred’s guinea-pig manager, and Quinn herself voicing the kids’ mum.

Although Quinn is credited as a director on all of her films, she cites Famous Fred as the one project where she acted as a director, being in charge of a team of animators. Her distinctive style was often subsumed by that of her collaborators, along with that of Posy Simmonds. Quinn has admitted that imitating the styles of other artists is not her forte, but the results here are actually quite interesting.

The two children, along with the guinea pig, appear to have jumped right out of Simmonds’ illustrations. Meanwhile, Quinn’s style is evident in the birthday party sequence, where the briefly-glimpsed partygoers appear to have arrived via Girls Night Out – the scene even has a cameo from Beryl. Fred himself comes across as a co-creation, with a design lifted directly from the book but an animating spirit that is unmistakably that of Joanna Quinn. In some ways he recalls the bulldog from Britannia, with fond parody of rock stardom replacing coarse satire of imperialism. As a caricature of a macho sex-god, he also has something in common with Body Beautiful‘s Vince, although the end result is far more lovable.

Quinn’s next major project was another collaboration, albeit of a very different sort. In 1998 S4C and the BBC followed up their earlier Shakespeare: The Animated Tales with The Canterbury Tales, an animated series where various studios in Britain and Russia adapted Geoffrey Chaucer’s poem. Moscow’s Christmas Films handled the bridging sequences depicting the pilgrim storytellers, while the other studios used a range of different styles to bring the pilgrims’ stories to life. Joanna Quinn and Beryl Productions were tasked with animating “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.”

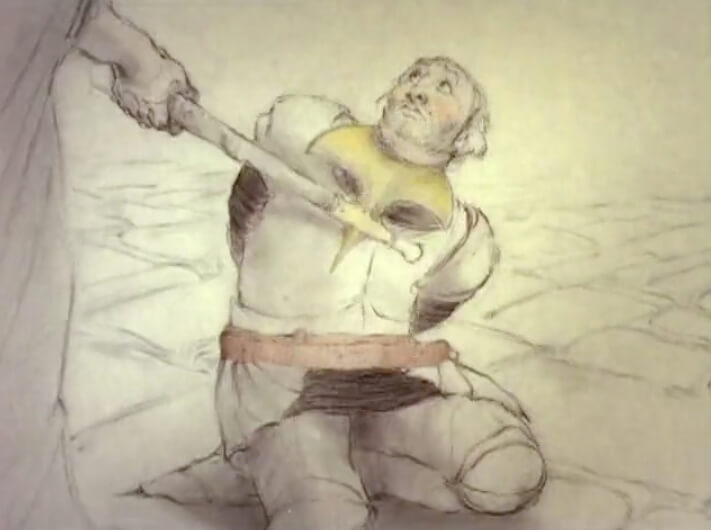

The story begins with an Arthurian knight raping a maiden. For this crime, he is taken before Queen Guinevere. She threatens him with execution, but offers to spare his life if he can find a satisfactory answer to a specific question: what is it a woman most desires?

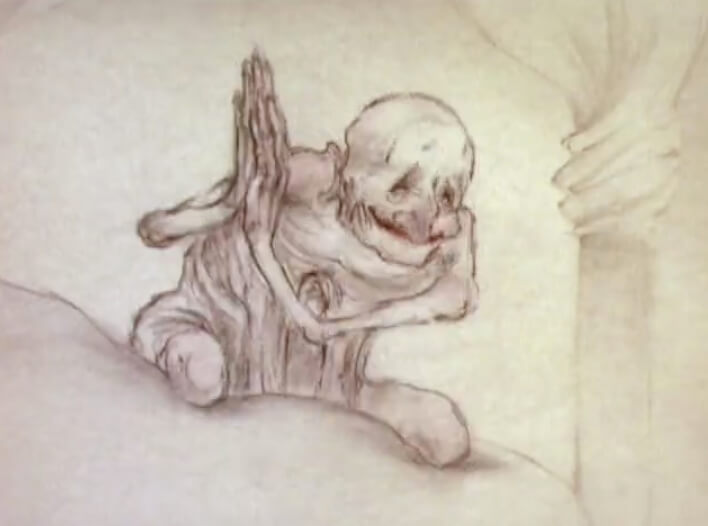

The knight speaks to a succession of men, but each gives him a different answer to the question. Finally, he comes to a mysterious and ugly old woman living in the forest. She tells him that what a woman desires most is her husband’s subservience. Guinevere and her court accept this answer and let the knight go free, but he is now faced with another concern: he must now repay the hag by marrying her.

The hag, it turns out, can alter her appearance. She can remain an ugly old woman, which will mean that her new husband will never be troubled by romantic rivals. On the other hand, she can turn into a youthful beauty – and sleep with as many other men as she chooses. The knight, in despair, tells the hag to choose whichever option suits her best. She announces that she shall be both beautiful and faithful, and the couple consummate their marriage.

A viewer familiar with Quinn’s earlier work may expect the film to parody Arthurian legend, perhaps approaching its material in the same way that Chuck Jones’ What’s Opera, Doc? handled Wagnerian opera. Instead, she treats her subject matter with a great deal of respect. Instead of her usual cartooning, she uses a more realistic style that ends up evoking the spirit of fantasy illustrators such as Arthur Rackham. That said, she also subverts a number of conventions along the way.

King Arthur is mentioned but never shown, making Guinevere the main authority; Quinn’s character animation is a joy to behold as the monarch strides, sneers, and generally shows her utter contempt for the pitiful knight brought before her. The rape victim, while given neither dialogue nor even a name, is more than a mere plot device: she is present through the courtly scenes, a flower in her hand serving to reflect her emotional state. The hag is not a wicked witch but a trickster figure, and a sympathetic one, rejected by the man she saved purely because of her appearance. Some of these elements are found in the source, but in each case Quinn succeeds in bringing a strongly feminist interpretation to the screen.

Quinn’s final change to the text comes at the very end. She disliked how Chaucer rewarded the knight with a beautiful wife: “I just couldn’t leave it like that, it was so wrong,” Quinn told us. And so, she depicts the hag returning to her wizened guise and cackling as the knight – unable to see her true form – embraces her. “She had revenge, because otherwise he didn’t get his punishment.”

During this period, Quinn also began working on TV adverts. Amongst other things, she was responsible for a long-running series of Charmin toilet paper commercials, which lasted from 1999 to 2011. Various different animals appeared in these ads but the grizzly bear was the most popular, and even starred in a 2003 picture book called The Adventures of Charmin the Bear; veteran children’s author David McKee penned the stories while Quinn provided illustrations.

The money that Joanna Quinn received for promoting toilet roll came in handy when she came to revisit that idea that had given her such an ambivalent response years before: a Beryl series.

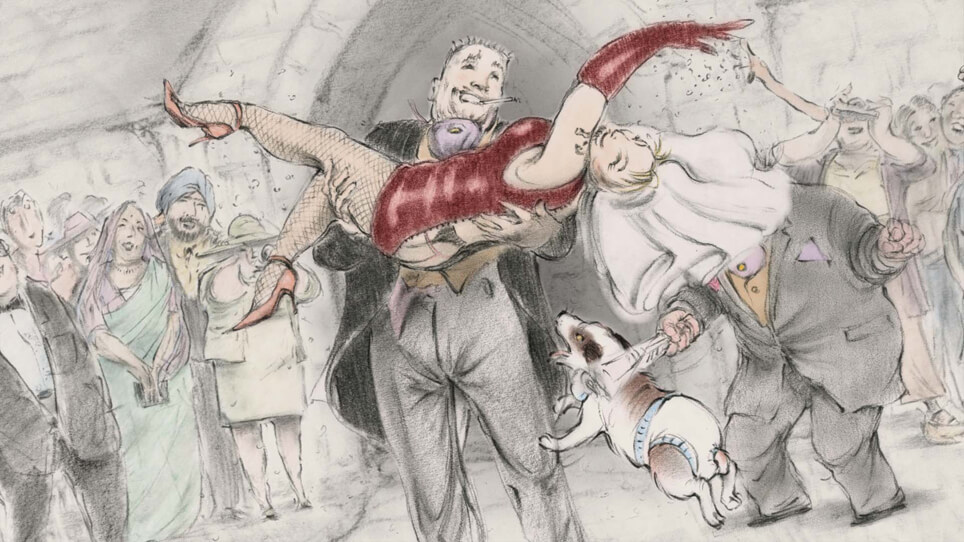

Quinn’s proposal for a series of Beryl shorts entitled Dreams & Desires was turned down by Channel 4, which had greatly lowered its commitment to animation since the days of Girls Night Out. Undeterred, Quinn — still working in collaboration with Les Mills — set about using advertising fees to fund the project This resulted in the 2006 short Dreams and Desires: Family Ties, in which Beryl takes her digital video camera to a friend’s wedding. She dreams of becoming the next Eisenstein or Riefenstahl, but ends up causing mayhem: amongst other things, one of her filmmaking tricks involves strapping her camera to the back of an over-excited dog.

As impressive as Girls Night Out and Body Beautiful were, Family Ties was, by a considerable margin, the most technically accomplished of the Beryl shorts thus far. Being framed as Beryl’s video, the film is shown largely from a first-person perspective; angles change wildly within a single shot, and some sequences have fully-animated backgrounds as Beryl fumbles with her camera. The events on-screen are unbridled mayhem, but the film itself is astonishing in its precision.

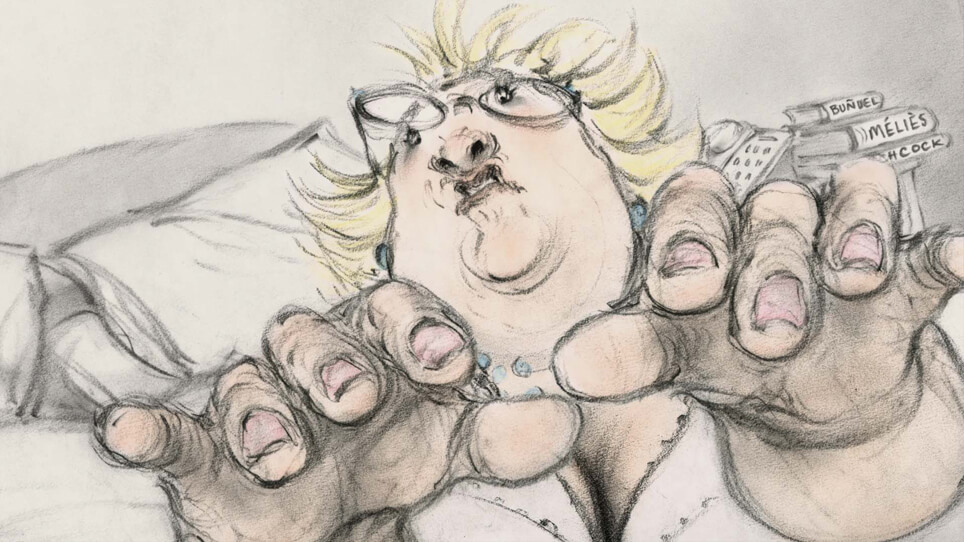

After obtaining support from a longtime animation benefactor located across the Atlantic, the National Film Board of Canada, Quinn and Mills moved on to the second Dreams and Desires short — although the series label had been dropped by the time the film was released in 2021. Entitled Affairs of the Art, the story this time sees Beryl confronting her regrets about never having gone to art school during her youth. Her obsessive attempts to create an artistic masterpiece (with her naked husband as model) are used as a framing device as she reminisces about some of the other obsessions that have appeared in her family: her grandmother was preoccupied with pickling; her son graduated from pigeon-fancier to trainspotter; and her sister Bev has harboured a raft of bizarre obsessions.

It is Bev rather than Beryl who turns out to be the main character this time. A series of flashbacks follow her passions from the animal maltreatment of her childhood, to the communism of her teenage years, and finally to the wholesale plastic surgery of her Californian adulthood. Affairs of the Art has the blackest humour of all the Beryl cartoons, with much of its queasy comedy deriving from death (both human and animal). It is also the quirkiest short of the lot. One memorable scene is a parody of Raymond Briggs’ The Snowman, with Bev being flown through the skies not by a frosty friend but by the reanimated corpse of Vladimir Lenin, uniting her twin preoccupations of communism and taxidermy.

The short turned out to be another hit, and at the time of writing is in the running for an Oscar. Beryl’s artistic ambitions may not have gone far, but she has cemented Joanna Quinn’s reputation as a major talent in modern animation.

Note: This is an updated version of an article that was originally posted at MsEnScene.com in 2018.