“When the Leeds workshop started there was very little challenging animation being done and as a result there was always an excited audience waiting to see what the next films would be.”

—Gillian Lacey

No discussion about the history of women in British animation would be complete without a mention of Gillian Lacey. Although her filmography is not particularly expansive, and her more recent work has moved away from cartooning, hers is nonetheless one of the strongest feminist voices to have been heard within UK animation.

No discussion about the history of women in British animation would be complete without a mention of Gillian Lacey. Although her filmography is not particularly expansive, and her more recent work has moved away from cartooning, hers is nonetheless one of the strongest feminist voices to have been heard within UK animation.

Gillian Lacey entered the animation world as a beneficiary of the British Film Institute’s Experimental Film Fund, which occasionally financed animated projects from outside the commercial mainstream. On a budget of £500, she put together a short film named Wanderings of Ulick Joyce, which was loosely based on a story by Irish author Flann O’Brien and completed in 1968. Although she had never previously animated, Lacey’s work on this short so impressed George Dunning’s studio TVC that she was recruited to work on its feature Yellow Submarine.

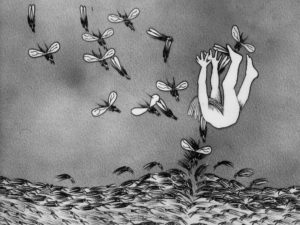

Lacey then went on to work for Halas & Batchelor. The most prominent animation studio in Britain at the time, Halas & Batchelor aimed to balance its output between populist productions (such as Disney-like features and Hanna-Barbera-like TV cartoons) alongside more experimental pieces. In the latter category was the six-part Condition of Man series from 1971, overseen by John Halas and Geoff Dunbar. Lacey contributed to the series by animating a short entitled Up, in which a gender-neutral character climbs a tower of humans while trying to reach a lotus flower at the top.

Lacey’s next short for Halas & Batchelor, also from 1971, was a two-minute piece called If By Chance we should Meet. This film is now lost due to print deterioration, but a synopsis is available on Lacey’s website: “A man and a woman meet and fall in love. However while she dreams of their merging together, he dreams of being swallowed up by her. A parasitic plant grows over them and they become skeletons inside it. One walks off. The other is left desolate.”

Working in the animation industry was not something that satisfied Gillian Lacey. After a seven-year stint as a teacher in London, she moved to Leeds; in the pages of Jayne Pilling’s 1992 book Women & Animation: A Compendium, she describes how this move coincided with a decision to focus upon politically-engaged films. “I worked for many years in commercial animation before moving north,” she writes, “but could no longer find meaning in the world of TV series and adverts. Living in Leeds, it slowly dawned on me that I could use my animation skills in a more political way.”

And so, Lacey teamed up with three other women to start the Nursery Film Group in 1976; their initial aim was to make a propaganda short calling for the government to invest in nurseries, hence their choice of name. Besides Lacey herself, the only person in the group to have prior experience in animation was Jenni Carter, but the other members brought additional knowledge of education, social sciences, and theatre to the table.

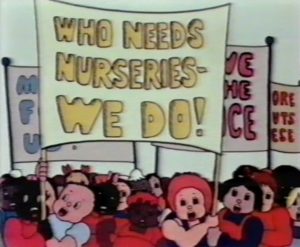

Backed by an array of charitable organisations, the group completed its film Who Needs Nurseries? We Do! in 1978. Designer Jenni Carter lent the short an aesthetic consistent with the cheap-and-cheerful style common to didactic cartoons on both sides of the Atlantic, from the British public information films of Richard Taylor to Schoolhouse Rock! in America. The film was screened at the 1979 Cambridge Animation Festival and later shown on Channel 4’s World of Animation strand in the 1980s.

The cartoon starts off with a male news reporter interviewing members of the public on the subject of childcare. First, he stops a passing man – who, as a football supporter, fits into a masculine stereotype. “It’s the woman’s job, isn’t it?” says the man. “Little kiddie needs its mother’s love, yeah.” The reporter visits a supermarket and meets the man’s wife, who is struggling to keep three unruly children together. When the conversation turns to nurseries, the woman expresses skepticism: “I feel sorry for those kids, being looked after by strangers – they need a mother’s love at their age.”

While the interview is taking place, the woman’s tiny daughter sneaks off to see some of her fellow toddlers. Together, the kids have a community meeting on the topic of nurseries. One of the children, Cecil, speaks up: “It’s your duty to stay at home ‘til you’re old enough to go to school, any fool knows that,” he says. “A child’s place is at home with its mother. My daddy told me, so there.” “Ha! I bet he only says that because he doesn’t have the trouble of looking after you,” replies one of the girls.

The kids come to agree that they would be better off in nurseries when their mothers are too busy to look after them. The only trouble is that there are not enough nurseries to go around, as demonstrated by a set of on-screen statistics. Were the government to fund additional nurseries, however, this problem would be solved.

The cartoon ends by cutting back to the news reporter. Having interviewed the two parents, he concludes that state-funded nurseries are a waste of money. But his words are drowned out by the singing of the children, who march in front of him carrying pro-nursery banners and placards. The motif of (male) authority and media figures being drowned out by activists would become a recurring one in the films that Gillian Lacey worked on.

By the time Who Needs Nurseries? was released, the Nursery Film Group had developed into Leeds Animation Workshop. Lacey and her collaborators continued their work, operating in a back-to-back house that they had converted into an animation studio. Despite their differing professional backgrounds they shared a set of ideals: they agreed that the Workshop would be an all-woman team; that the animators would be given equal pay; and that their films would be made as a collective, with none of the animators being given individual credit. They also adopted an aesthetic principle based around, in Lacey’s words, “use of style that is accessible to a wide audience combined with the creation of cartoon women who do not have huge tits and eyelashes.”

In 1980 Leeds Animation Workshop made its second film, Risky Business, about hazards in the workplace. Instructional animation on this topic was nothing new by then, but Risky Business stands out due to its activist slant: It argues that the best way for a worker to avoid hazards is to go to the authorities and demand better working conditions. In 1981 came Pretend You’ll Survive, an anti-nuclear film parodying the “Protect and Survive” public information campaign of the ’70s and ’80s — a campaign that received widespread ridicule for its ludicrous advice on surviving a nuclear war by, amongst other options, lying in a ditch with one’s head covered.

Pretend You’ll Survive begins with a woman watching television, and seeing various images flicker on the screen; whenever an image relating to warfare or nuclear catastrophe appears, a cartoon arm emerges from the set and daubs the screen with whitewash, leaving only images of domestic tranquillity. In desperation, the woman heads over to the window and looks out to see a gigantic skeleton striding the world, sowing nuclear symbols like seeds. Distrust of the media, as seen in Who Needs Nurseries?, turns up once again.

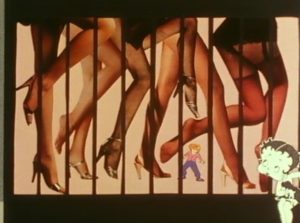

With its fourth film in 1983, Give Us a Smile, Leeds Animation Workshop mounted its most scathing attack on the establishment. The film depicts a woman being heckled and catcalled by male passersby as she walks about town; for the dialogue in this sequence, the Workshop’s members collected anecdotes from numerous women, meaning that the various catcalls (“Nice bum!” “Give us a smile!” “Can I have a lick of your lolly?”) are taken from real life. The woman’s physical surroundings are, likewise, a collage of everyday sexism: shops are plastered with sexualised advertisements or covers to pornographic magazines, while the other townspeople are clipped from cartoons depicting sexy female characters, often being harassed by male figures.

The main character sits on a bench and reads a newspaper, which turns out to be an assortment of real-life headlines reporting on women being raped or murdered by men. She sings about her emotional response to all of this: “Why do the things that they say/Have to dominate my day?/Every window that I see/Tries to tell me how to be!”

She then walks past a series of paintings that illustrate the Madonna-whore dichotomy. The first is an artistic nude; the second the Virgin Mary; the third Fiona Butler in the iconic “Tennis Girl” poster; the fourth an illustration of a sentimentalised little girl. A pair of godlike fingers pick the woman up and place her into the pictures, posing her to match the two-dimensional characters.

All of this is intercut with live-action sequences set in a police station; again, the dialogue is taken from personal anecdotes collected by the filmmakers. Male officers ask a series of probing questions of rape survivors: “What were you wearing at the time?” “Did you have your hair up or down?” “Did you smile at him first?” “What were you doing out on your own at 11 o’clock at night?” These become increasingly personal: “Were you having a period at the time?” “But you didn’t scream for help, did you?” “Do you have daydreams of being overpowered?”

When the animated protagonist arrives at her home, she turns on the television and is greeted by a bevy of scantily-clad dancing girls. Thrown into a rage, she opens up her television set to reveal a miniature studio inside, and sweeps away the male crew members with her hand. The television picture changes to an advert-like sequence where a group of women sing a jingle: “Time to change the programme/Time to change the song/Now you’ll see us smiling/But don’t you get it wrong/We’re making our pictures/We’ll dance to our own tune/So everyone get ready/’Cause there’ll be some action soon!”

The woman then goes out once again, this time with renewed vigour. Men continue to heckle her; she responds by grabbing their words, which appear onscreen, and throwing them back into the men’s faces. The background women cribbed from saucy cartoons spring to life and shake off their male harassers. Female hands appear and deface the sexualised advertising images.

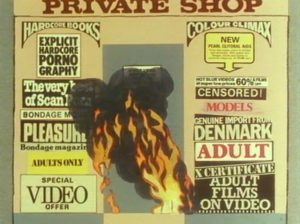

In one of the live action sequences, a male judge (whose dialogue is credited to the real-life Judge Sutcliffe) throws aspersions on women who report rape: “It is well known that women, in particular, and small boys, are liable to be untruthful and invent stories. It is dangerous to convict on the uncorroborated evidence of a woman. Rape is a charge that is easy to make and hard to prove.” But his words are drowned out by the voices of outraged women, while the live action men fade into absurd cartoons. The film ends with a pornography shop catching fire and burning to cinders.

This image is not purely symbolic. In the years running up to the film’s release, Leeds had seen a spate of arson attacks on porn shops; a group known as “Angry Women” took credit for these crimes. Finn Mackay, writing in the 2014 book Understanding Gender Based Violence: National and International Contexts, summarises this nebulous organisation:

“This appears to have been an informal, unstructured network of individual feminist activists and small groups, who were engaged in what is known as non-violent direct action, or NVDA, particularly against the pornography and prostitution industries which, it will be recalled, were new sites of feminist analysis […] ‘Angry Women’ became a moniker for a variety of NVDA carried out across the country, particularly in large metropolitan cities, and most dramatically in Leeds. It was in Leeds that ‘Angry Women’ took action against pornography by committing 18 acts of arson against so-called ‘sex shops’ between 1981 and 1983. No adjacent property was ever damaged in any of the actions, nobody was ever harmed, and to this day nobody has ever been linked to or charged with the offences.”

Give Us a Smile implicitly endorses these arson attacks. In the feminist TV ad watched by the protagonist, the onscreen women hold up a a pencil, a paintbrush and a can of spray paint – presumably for use in the defacement of sexualised adverts, as seen shortly afterwards – along with a box of matches. At the end of the sequence a hand emerges from the TV screen and offers each of these objects in turn to the main character. Later on, the protagonist looks on with approval at various newspaper headlines, amongst them “‘Angry women’ responsible for sex shop fire” and “Fire guts porn shop.”

To fully understand the context behind this extremism, it should be remembered that Leeds was one of the locations in which women were murdered by Peter Sutcliffe, the serial killer known in the press as the Yorkshire Ripper. Thirteen women lost their lives to Sutcliffe between 1975 to 1980, and radical feminist organisations such as Reclaim the Night and the Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group blamed on patriarchal society. This argument turns up in Give Us a Smile: while at home, the protagonist turns on the radio and hears a male announcer advising women to stay at home after night. She then dances with joy when this voice is replaced with a female announcer advising men to stay home after night instead.

The Give Us a Smile VHS was accompanied by a booklet expanding upon its subject matter. Amongst other things, the booklet argues for the banning of pornography, citing the urban myth of porn involving “the actual murder of a woman on film, as in the American so-called ‘snuff’ movies” as one reason that the adult industry is dangerous. As the product of a rather austere second-wave feminism, Give Us a Smile stands in sharp contrast to the more sex-positive animation that Thalma Goldman Cohen was producing during the 1970s and 80s. At around the same time that Gillian Lacey was helping to set up Leeds Animation Workshop, critics debated whether Goldman Cohen’s Amateur Night – in which dumpy, unglamorised cartoon women perform stripteases – was misogynistic or pro-feminist. One can only imagine what Give Us a Smile’s put-upon protagonist would have made of that film.

Give Us a Smile was the last Leeds Animation Workshop film to count Gillian Lacey amongst its creators. Lacey began to feel frustration at the restrictive nature of the group that she had co-founded, as she explains in Women & Animation:

“My vision of the workshop was to expand the group, to have visiting animators from whom we could learn new skills, to have movement within it, working on individual projects, taking on placements, expanding into live action. The others felt they were not ready for that. They felt that all the necessary skills were there within the group and that animation should remain the focus. So I left.”

Lacey has sometimes been portrayed as the driving force behind Leeds Animation Workshop, although this does a disservice to the other members of the group – as evidenced by the fact that the Workshop is still in operation today, decades after Lacey’s departure, with a more refined technique.

Clare Kitson argues in her 2008 book British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor that the early Leeds Animation Workshop films are “rather unsubtle and propagandist… very much products of their time.” Lacey, in her 1992 retrospective on the group’s work, makes a similar point: “it is perhaps time to make a critique of the socialist/feminist imagery used in both animated and live action work in the last few years,” she says. “Audiences can feel patronised by films that fail to acknowledge their ability to ‘read’ meaning.” As she continues:

“Although there is still an audience for ‘propaganda’ animation in what has become the Leeds workshop’s house style, I think that in opposition we need to keep up not only with the issues but with the means of conveying them.”

Lacey had already shown that she was prepared to put her money where her mouth was. In the 1980s she assembled a team of feminist animators and cartoonists – including Monique Renault, Marjut Rimminen, and Christine Roche – and pitched a series of auteur shorts to Channel 4. Entitled Blind Justice, the four-part series was to focus upon discrimination against women in the legal establishment, a subject that Lacey had researched while working on Give Us a Smile. Channel 4 agreed to fund the series, which was completed in 1987.

Lacey’s main contribution to the series was a short entitled Murders Most Foul, which shows a greater degree of consistency and precision than the early Leeds Animation Workshop films. In the 2005 documentary series Animation Nation, she described how she came to conceive of this short:

“I chose to do this one about murder, because I just felt so outraged at some of the judgments that I’d come across, and that way in which the women were seen as to blame, and men were often given quite light sentences. I used the style of melodrama because there is a sense of theatre in court procedures for me. There’s a kind of absurdity about it.”

The film blends the courtroom with the theatre: near the start, a judge introduces the trial as “a melodrama in fancy dress.” The defendant is a man charged with murdering his wife; he pleads not guilty, and receives the full support of the court. Meanwhile, the dead woman’s ghost and a pinkish female angel watch from above, jeering with sarcastic derision at the man’s version of events. While the murderer outlines his narrative, the onscreen animation shows the woman’s side of the story. He portrays himself as a long-suffering, hen-pecked husband; she depicts him as drunken, violent, and guilty of marital rape.

The flashback ends with the woman entering a same-sex relationship; this is shown to be healthy and fulfilling, although the male judges express disgust. The murderer is eventually let off, having served a ten-week jail sentence, while one male member of the court waves a banner reading “YOU CAN GET AWAY WITH IT YOU KNOW BOYS.” Disgusted, the two women decide to speak up. Just as the reporter in Who Needs Nurseries? was drowned out by singing children, and just as the judge in Give Us a Smile was drowned out by outraged women, the courtroom in Murders Most Foul is disrupted by the dissenting voices of the female ghost and angel.

Amongst the other three films in the series is Someone Must be Trusted by the satirical cartoonist Christine Roche. Due to Roche’s lack of hands-on experience in animation, she collaborated closely with Lacey in making the short. Most of the animation is Lacey’s work, while the storyboard and designs were handled by Roche, whose distinctive drawing style is evident throughout the film.

Named after a comment by Lord Denning (“Someone must be trusted; let it be the judges”), the film is divided into three segments. The first, “The Family Wage”, involves a black woman who finds that she is paid less than her white male co-worker; she writes a letter to an industrial tribunal, which ultimately rejects her case. “I’ve got a family to support,” says the male worker, oblivious to the fact that the woman has two children in tow. In the second part, “Virgin or Whore”, a woman is raped while hitchhiking. She takes her case before the court, which is portrayed as a distorted, gothic landscape ruled over by gargoyle-like judges. “She ought to think herself lucky,” remarks one of the leering male justices; “no-one’s ever tried to rape me.” The case is dismissed on the grounds that the woman was hitchhiking at night while wearing jeans, and therefore “asking for it.” The final sequence, “Fallen From Grace”, is a spoof opera about a woman charged with murdering her husband.

Following its completion, Blind Justice was screened at festivals but struggled to find a place on the channel that produced it. “[S]ome at Channel 4 felt one or two of the individual films were behind the times in their approach to feminist issues, a bit heavy-handed perhaps,” wrote Clare Kitson in her book. The series was eventually aired as part of the 1990 Women Call the Shots season – but as the BBC had aired an unrelated series called Blind Justice in the interim, it had to be renamed In Justice to avoid confusion.

Lacey initially hoped that the auteurs behind Blind Justice would continue to produce similar work as part of a group called Smoothcloud. However, certain members had different plans for the future, while Lacey herself suffered from health problems. Amongst the medical issues faced by Lacey at this point in her life was claustrophobia, a subject that she decided to tackle in her next foray into animation.

While working as a teacher, Lacey met an animation student named Darren Walsh. Walsh had been working with a technique known as pixilation – a form of stop-motion animation in which actors, rather than conventional models, move frame-by-frame before a camera to create a juddering, surreal effect. Walsh’s variation on the practice involves placing the actors inside grotesque animated masks. Years later he would put this technique to comedic use in Angry Kid, an online series made with Wallace & Gromit creators Aardman Animations. Given the laddish sensibilities of his own work, Darren Walsh may seem an unlikely collaborator for the British animation’s staunchest feminist; and yet, their team-up resulted in a striking short film that mixes animation with documentary.

Completed in 1995, Gotta Get Out was written and directed by Lacey and focuses on a claustrophobic woman, played by Alison Steadman, whose experiences are based on Lacey’s own. Most of the film is live action and shot in a first-person perspective. When the protagonist enters an enclosed space such as an aeroplane or lift, she has a panic attack; at these points Walsh’s pixilation comes into play, and everyday figures – flight attendants, fellow passengers – morph into nightmarish visions.

By this time Lacey had started to move away from animation. In 1992 she had made the short live-action documentary Capoeira Quickstep, in which she examines the impact of Brazilian dance in Britain and re-evaluates her personal misconceptions about Latin American culture. This interest in dance would inform much of Lacey’s subsequent live-action work: she teamed up with various dancers and choreographers to create the short films Dancing Inside (1999), Dancing Under the Dustcover (2000), Horizone (2001), Under/line (2001) and Play: On the Beach With the Ballets Russes (2008).

But the spirit of the animator remained in her work. Gotta Get Out had demonstrated how animation and similar techniques could be used in conjunction with live action to portray subjective experience and internal emotional states; this was an avenue that Gillian Lacey continued to pursue.

Her 1996 documentary Album, part of BBC2’s Picture This strand, is a based around a turn-of-the-century photograph album that Lacey found in the 1960s. The film follows her as she visits the Yorkshire locations depicted in the album, encountering relatives of the photographs’ subjects. On her blog, Lacey outlines how she used digital imaging techniques as a substitute for more conventional documentary language, once again showing dissatisfaction with mainstream media practice:

“I intensely dislike the style of documentary where a person with memories is walked round a building or site that has been significant and says ‘I remember when’ ‘this is where such and such happened’. It conjures up little for the viewer who was not there and does not have the memory in their head. I used some of the photos from the album and as closely as possible took shots of the same places now. I then faded the one into the other (this is easy now but digital technology was in its infancy when I made the film). This evoked places then and now without the need of verbal explanation. Apart from that I used landscape and buildings to show an atmosphere rather than being tied to specifics.”

In 1998 Channel 4 ran a season of programming about abortion, which had been legalised in the UK thirty years earlier. Gillian Lacey contributed to this season alongside Marjut Rimminen, one of the directors of Blind Justice, by working on a four-part series entitled Mixed Feelings. Each film in the series interviews a woman who has had an abortion; the live-action is accompanied by visual effects, including animation, to illustrate the emotions of the interviewees. “The look of the series has become very widely used since then,” comments Lacey on her website.

Lacey’s subsequent work with the moving image has expanded to include performing arts. She teamed up with sculptor and Holocaust survivor Maurice Blik for the 2008 performance piece Second Breath, where onscreen images mingled with live music to create an audio-visual interpretation of Blik’s life and work. As with Gotta Get Out, Second Breath saw Lacey work alongside one of her former animation pupils – this time Gemma Carrington, who adapted photographs from Blik’s childhood into moving images.

Lacey’s most recent film is My 60’s Diary, which she uploaded onto Vimeo in 2016. This is based around a diary that she kept while living in a hippy commune for three months in 1969; a video collage, it mixes readings from the diary with Lacey’s photographs and sketches from the same period.

The filmography of Gillian Lacey shows a definite restlessness. In her decades of work she has shifted from technique to technique and from collaborator to collaborator; starting with mainstream animation, she moved into feminist agitprop, and then broadened into experimental live action.

Her work and career were both shaped, above all, by dissatisfaction: dissatisfaction with commercial animation; dissatisfaction with the alternative offered by animation collectives; dissatisfaction with mainstream documentary practice; and dissatisfaction with various aspects of society. Throughout her time in film, Gillian Lacey has shown the ability to adapt to her circumstances, taking this discontent and channelling it towards creative work that is innovative and vital.