Thank you for joining us once again as WWAC continues its trip through the 2021 Hugo Award finalists with reviews of two more stories in the Best Novelette category…

“The Pill” by Meg Elison

The main character of “The Pill” is an unnamed teenage girl who, like her parents and brother, is fat. The shape of her family quite literally changes with the arrival of a new diet pill. The mother is the first to try it while it is still at an experimental phase; the results are disturbing for the household – the others being forced to listen as she screams in the bathroom – but the pill is a success and her pounds drop by the dozen. The daughter, however, is still unsure about this miracle weight-loss method, the workings of which she describes in graphic detail:

It was the same in that first trial as it is now: you take the Pill and you shit out your fat cells. In huge, yellow, unmanageable flows at first. That’s why they scream so much. Imagine shitting fifty pounds of yourself at a go. Now, people go to special spas where they have crematoiletaries that burn the fat down. […] Toward the end, Mom (and everyone like her) shit out all their extra skin, too.

The pill catches on with the public and the girl’s other family members decide to try it. Not all of them survive, however. It turns out that the pill has potentially fatal side effects: one in ten people who take it will die. Even as fat people begin slimming en masse around the world, the story’s protagonist is faced with a question: does she hate her body enough to take the risk?

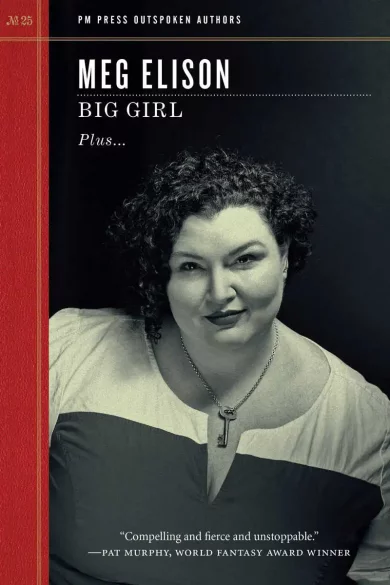

The term “body horror” is widely applied to fiction portraying various types of corporeal violation, from straightforward injury to fantastical mutations. “The Pill”, from Meg Elison’s collection Big Girl, could be termed a story of body horror; but if so, this is body horror of a distinctly psychological type. The story has an element of conventional body horror, as when we learn exactly what happens to the unlucky one-tenth of pill-poppers (“They ended up slumped on a toilet, blood vessels burst in their eyes, hearts blown out by the strain of converting hundreds of pounds of body mass to waste”) but more emphasis is placed upon the characters’ attitudes towards bodies.

Cultural revulsion at the bodies of fat people is central to the story. Even the protagonist partakes in it, salving her self-esteem by reassuring herself that she is, if nothing else, less fat than her brother Andrew:

He’s way fatter than me, so I feel like I’m allowed to be disgusted by some of his habits. Andrew can’t sit or stand without making a guttural, bovine noise. I’ve seen crumbs trapped in the folds of his neck. I used to work really hard not to be one of Those Fat People. I was obsessively clean, took impeccable care of my skin. I never showed my upper arms or my thighs, no matter what the occasion. I acted like being fat was impolite, like burping, and the best thing to do was conceal it behind the back of my hand and then always, always beg somebody’s pardon. I didn’t know anything back then.

Of course, such attitudes are turned on their heads with the arrival of the miracle cure for excess baggage. The phenomenon of fat people suddenly becoming thin prompts a varied range of reactions from the world, allowing “The Pill” to take its share of satirical swipes. Once the mother slims down, the father becomes anxious that she might grow unfaithful to him (“because fat girls don’t fuck, I guess?” muses their daughter). Meanwhile, the daughter’s amateur movie-making group proposes a short film about her eating food in a cage while people stare (“I didn’t know how that would get anything meaningful across, and they didn’t know how not to be thin assholes. So we dropped the idea.”)

A significant detail is that those who take the pill (and survive) are granted not just slim bodies, but identical slim bodies – lending them an uncanny, clone-like quality. At the start of the story, the protagonist stands out because her society views her body as wrong and unnatural; by the end, she stands out because she is one of the few people not to have given themselves an unnatural, artificial body. This could have been a simplistic parable about body image, but Meg Elison adds layer upon layer of honest feeling to the story’s skeleton.

“The Pill” is peppered with sharp emotional insights: in the very first paragraph, the protagonist speculates that her mother signed up for the university study (ultimately leading her to take the still-experimental pill) because the researchers “would ask her questions about herself and listen carefully when she answered. Nobody else did that.” The story is very humorous – but the humour is laced with sadness, anxiety, and elements of outright horror.

A story with a simple premise can work if all of the pieces fit together. In “The Pill” we find a well-drawn set of characters, an astute vision of their surrounding society, and a central plot device that sends just the right set of ripples through it all. The result is a story that, while not always pleasant to read, remains intelligent and humane throughout.

“Monster” by Naomi Kritzer

The plot of “Monster” is divided into two threads taking place at different times. The past-tense strand sees protagonist Cecily Grantz meeting a boy named Andrew in high school during the eighties, after which a relationship forms between the two. The present-tense portion of the story, meanwhile, introduces us to a grown-up Cecily – now a professor of genetics – as she takes a trip to China to meet Andrew once more. As the two strands grow and develop, they are united by a single narrative: the dark story of Cecil’s falling out with Andrew and her equally dark reasons for seeking reunion.

The novelette has a lot to say about bullying and the rule of the misfit. Teenage Cecily is a nerd, something which – as her adult-self mentions while narrating – was the opposite of cool in the eighties, rather than a variety of it as today. Her friendship with Andrew and his girlfriend opens up a new social circle for her, allowing her to no longer be a misfit; or, at least, to join a group of united misfits. But this happy story of a nerdy girl finding acceptance has an undercurrent of creeping unease, one that becomes apparent when Cecily runs unto Andrew’s ex-girlfriend:

“You know he has a dead rabbit in his freezer? Or did. He was going to dissect it.”

Nadine clearly expected a response, but my main question was, was she saying he killed the rabbit or did he just find a dead one, because . . . I mean, we cut up animals in advanced biology. They were from a supply house, of course, not picked up off the street, but . . . I didn’t know how disturbed to be about the whole idea.

“He wanted me to watch,” Nadine added.

“Ugh,” I said, sympathetically.

“He talked about wanting to know what everything looks like on the inside. Everything. Just . . . I don’t know, Cecily. Be careful, I guess.”

“Monster” is an appropriate stablemate to fellow Best Novelette finalist “Burn or The Episodic Life of Sam Wells as a Super” by A. T. Greenblatt. Where that story portrayed a mundane grind beneath the glamour of a superheroic universe, Naomi Kritzer’s story inserts a supervillain origin story into what at first seems no more than the tale of a high school reunion.

It is fitting that “Monster” uses an object – the body of a dead rabbit – as the first signifier of Andrew’s monstrous aspect: throughout the story, Kritzer establishes the outlooks of the two main characters through their interactions with objects. The passing of time and setting is conveyed partly with items of food – chips in high school, dishes unfamiliar to Cecily in China. Clothes are another reference point, with Cecily’s preferred attire leaving her feeling out-of-place both in China and in the high school of her youth. Objects also turn up as offbeat similes: “The tea farm is somewhere near here, and I can see the leaves unfurling in the water like those children’s toys that go from a tiny little capsule to a full-sized giraffe-shaped sponge when you drop them in water.”

Most significant of all the object-symbols are books. Cecily and Andrew initially bond over their mutual love of science fiction novels, with the story namechecking Isaac Asimov, Piers Anthony, William Gibson and “all the older Anne McCaffrey” – shades of Kritzer’s other Hugo finalist for the year, “Little Free Library”. The two characters discuss the tactility of books together, a moment so important that the first use of the story’s title comes after Cecily admits to dog-earing pages instead of using bookmarks: “You do realise that makes you an actual monster”, says Andrew.

The attitudes of the two characters are defined ultimately by where they see the boundary line between objects and people. Andrew uses human beings as test subjects for his deadly experiments, while geneticist Cecily sees the human body as being built up of innumerable building blocks – although, crucially, she retains compassion:

There are basically two approaches to genetic diseases. The first is to test people—this has gotten cheaper and easier every year—and discourage carriers from having genetic children with other carriers. If one parent carries the gene for cystic fibrosis, but the other doesn’t, none of their children will have the disease. The problem with this approach is that because carriers will continue to have children with noncarriers, the genes themselves stay in the population and at least a few babies with genetic diseases are more or less inevitable. (Please note, I’m not talking about eliminating neurodiversity from the population, or anything that could possibly be a reasonable human variation. I’m talking about diseases that cause years of misery and an inevitable early death, like cystic fibrosis, or diseases that just kill any child unlucky enough to have them, like Tay-Sachs.)

Although surrounded by (mostly) inanimate objects, Andrew and Cecily are themselves rather more animated and mutable. “Monster” plays with the yin-and-yang dynamic that comes with hero-villain pairings. As we grow to know the two characters, we find that protagonist Cecily is capable of moral ambiguity while Andrew – as ruthless as his methods may be – turns out to have motives that are not entirely selfish. The theme of change, or the potential for change, receives unmissable symbolism when Cecily attends a Chinese stage play about transformation:

In the staging, the tree is silver and resembles the hats the women here wear; I’m not sure if those hats are supposed to symbolize the tree or vice versa because the program doesn’t tell me. Both the man and the woman reach the tree and are told that one of them will be given the gift of the seeds but the other will be demanded as a sacrifice.

Both try to be the sacrifice; the man is pushed back as the woman’s sacrifice is accepted. She ascends to the back center of the backdrop and then raises her arms to be transformed into wings; lights, video, and flying wires are used to change her into the golden pheasant for the performance, although she looks rather more like a phoenix. The man, temporarily forgotten, regains the spotlight as she flies away and he’s blown back by the wind from her wings. Weeping, he takes the seeds back to his people.

I find myself thinking about how you would transform a human woman into a golden pheasant with gene editing and wrench my thoughts away from that particular abyss.

In the high school portions of the story, we see Cecily and Andrew each growing and transforming into new selves that their parents find objectionable. Andrew, confident in his own intellect, becomes apathetic towards his grades; Cecily, meanwhile, fails to meet her mother’s standards of femininity, particularly when she fights back against bullies. Yet for all of these changes, when the characters meet as adults they find that their old high school friendship – and all that comes with it – is never far from the surface.

“Monster” is a cleverly constructed, character-based story that is entertaining on the first read through, and has enough depth to reward subsequent revisits.