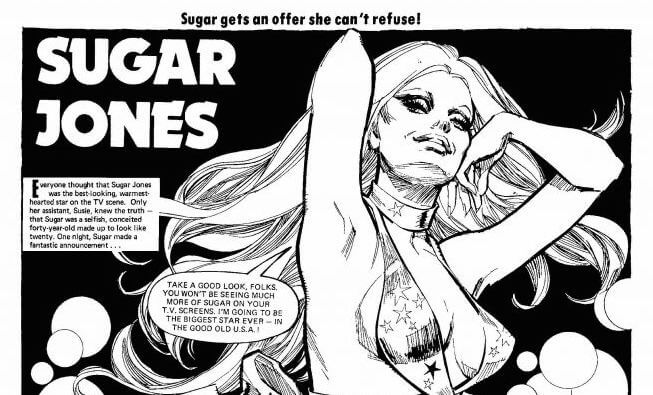

Sugar Jones is a girl comic from a 1970s teen magazine, Pink (1974-(1979?), and at first glance, this volume of collected strips is all about commonly denominated ~girl stuff. Fashion! Make-up! Great big hair and enormous eyelashes, size-threatened only by the circumference of her bellbottoms! And these excellent and diverting aspects are certainly present throughout. Sugar is a TV star and It Girl of her day, and she’s happening. But they, that glamour, are not what Sugar Jones is “about”—as befitting a strip conceived and originally written by Pat Mills, Sugar Jones is about class warfare and worker status. Let us not find this incongruous or confusing: 1970s magazine-reading girls were very often preparing themselves to enter the workforce, whether sooner, as seen in sister publications like Patches, My Guy, and Fabulous 208, or later.

The Best of Sugar Jones

Rafael Búsom (artist & co-creator), Pat Mills (writer & co-creator)

Pink Magazine for IPC, collected by Rebellion

November 25, 2020

Sugar Jones, though titular (and how—thanks to the nominative determinism of artist Rafael Búsom), is not our heroine. She’s the villain: the boss. Her textually negative status was what drew me to this book like a nail to a magnet—the advertising copy in the back of earlier Rebellion-released Misty reprints makes it immediately plain (as taken from the intro text opening every three-page strip): Sugar’s gorgeous, and famous, but she’s ACTUALLY OLD, and mean with it. “Forty made up to look like twenty!”—I love it. I love it! The scandal!

A detour into problematism: sure, it’s congruent with misogynistic patterns to suggest that forty is too old to be pretty, that makeup is dishonesty, that oldness is feminine villainy. But Sugar Jones is not inventing that wheel, and it doesn’t drive any of those points home in the actual dialogue or events of the comics themselves. This is simply digest text, the tl;dr of the serial: it tells us enough that we can understand where Sugar stands in the context of our world and hers; what her platform is; what she wants, what status she is invested in protecting. It’s effective storytelling through the use of familiar motifs without being actively cruel.

As we read the strips in this book, we find that the construction of Sugar’s cage is uninteresting to the narrative eye. What’s important about her is the status of her presence: that she’s somebody, no matter how she became them or how she acts to keep that placement. She’s in charge, she‘s the boss, she’s rich, and she’s actively conservative towards her wealth and status. Mills, or whoever wrote these scripts that he personally declines authorship of, was far more interested in emphasising that people who leverage desirability or power to others’ detriment are nobody to root for; that people who gain wealth and authority and even charm and beauty only to use them for personal betterment and recursively selfish ends are the destructive ones, the people we must workaround.

Sugar is never discovered as an old hag — even almost — and so her technical insecurity is not the vital part of her personality. Her meanness and venality are. Even the plain joy Búsom takes in drawing pin-up spreads of Sugar, cheeks out, sideboob akimbo, just feels like feminine luxury here where it’s textually part of Sugar’s lifestyle, job and nature. The text never punishes her for being sexy, it judges her by what she uses her appeal for.

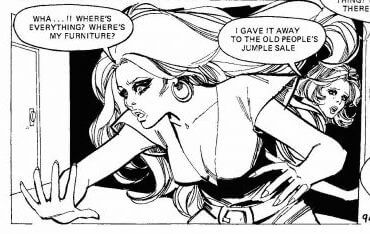

The real heroine of this strip is Susie, Sugar’s personal assistant, and just as happy as Sugar to change her hair with the fashions and paste on three pounds of eyelash every morning—god bless her for it, as every stroke of Búsom’s pen is welcome. She’s the employee, and so she’s the one we’re directed to root for. She’s also a nice person and perfectly aware of how flighty and shallow Sugar is. Every strip Sugar gets an idea, often or always about how she can gain—men, contracts, cache, cash—and Susie sets out a reason or two why pursuing that plan would be harmful to others. Sugar doesn’t care; Sugar goes for it. Susie, with a little help from whoever else is in the strip this week, thwarts it and all of the people poorer and more authentic than Sugar bask in the joy of collaboration, justice and geniality. These are extremely jaunty, momentary reads, perfect for a pause with a beverage or between naps in the sun. They’ve got conviction, tremendous aesthetic value, and no apparent hate in their heart.

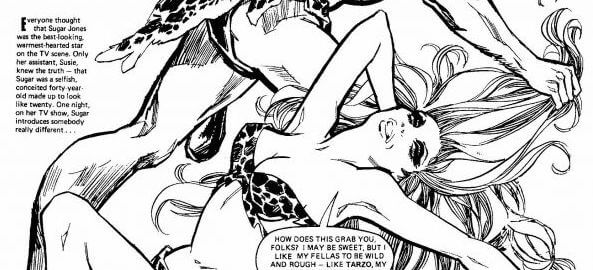

There is one strip I’d have left in the archive, though, simply because white-run British publications talking about African jungles and featuring palanquin-bearing Black characters who get no lines is a big old “Hey! Socially, we’re racist, and have been for ages.” The strip in question is a Tarzan riff, with Sugar bringing back a plane-crash white baby who was raised by animals and is now a super-hunk; the African elements and characters are entirely for set dressing. Without this strip I believe I could recommend this book wholeheartedly—with it, I’d want to make sure anyone I recommended it to was prepared to meet this casual reminder of ongoing anti-black colonialism.

If this strip is Mills’, it was almost certainly published in the time when his grasp on racial justice was poor; while he included an entirely positively drawn, all-Black cast in the Harlem Hellcats strip in 1977, as founding editor of 2000AD (a successful strip which continued even after their storyline ended; a new title and a new field for the characters to perform on kept them in the magazine), he also blithely used racial caricature here and there in other, whiter late 70s strips, making the casually-included Black African servitude hard to swallow from him specifically, at this specific time (for evidence of growth or recognition, he describes the thoughts and conviction that lead to working with a Black co-creator on Third World War book two in 1989). It is presented with textually affected neutrality (i.e. no jokes at their expense, and the assumption that presentation of things that happen is not connected to greater forces behind those happenings)—but even if that strikes you as an alleviator, and even if it isn’t Mills, it’s still the same wicked template that informed him in the first place. British Whiteness in the 1970s, as ever, was about idealising and idolising thin, swishy-haired white women and not worrying about the labour or subsequent, directly-resultant, contextualising of Black people. Though Sugar Jones as a property, or a thought experiment, tells us that youth and beauty and riches and influence are ethically bankrupt goals that don’t make for socially functional people, it is working from the surface backwards, and not backwards very far.

There’s a strip where Sugar goes up against a Black, American rival, also called Sugar Jones, also gorgeous and glamorous and flying high on stardom—and of course loses. It edges marginally around the notion of appropriation (Black Sugar was named that at birth, White Sugar picked it for her image) but doesn’t equate their rivalry or White Sugar’s sabotage of Black Sugar’s performance with racism. White Sugar doesn’t receive any more comeuppance than usual (Black Sugar wins the day and continues to be a successful and impressive winner) and her enmity is textually based in brand encroachment and misanthropy. One can say “perhaps White Sugar Jones is just a horrible non-racist,” and OK, devil’s advocate, perhaps she could be, but one can’t ignore that socially, structurally, pretending that race prejudice could be nowhere near a fight between professional, creative hotties leads us down a bullshit path.

No doubt some readers used the cognition inspired by Sugar Jones’ basics of labour politics to delve further, and into intersectional social theory—no doubt some didn’t. If the reader’s response defines the text, including the Tarzan strip is either a mistake, a continuation, or an act of deep honesty. To my mind, Sugar vs Sugar is similar, but I’d certainly still have picked it for this publication. Is that ultimately dishonest, because an example of white normativism that gives a Black character a place in glory reinforces that same white normativism? It’s quite possible. I guess my response is ongoing. I also suppose that—ongoing, evolutionary response—is the point of the study of history, which reprint volumes are an industrial wing of.

So, as it’s printed, I guess I have to say Sugar Jones is doing what she should.