The apocalypse came with the push of a button. No one knows why, but the great wizard Soumaoro simply blew up the world one day. New leaders have arisen in the aftermath, though not all have the best interests of the people in mind. No one has thought to ask why Soumaoro destroyed the world because they are too busy surviving, until a young prince and his storyteller are summoned to seek the truth in Juni Ba’s Djeliyah.

Djeliya

Juni Ba (writer and artist)

TKO Studios

July 6, 2021

Djeliya (pronounced ja-LEE-ah) is a stunning meld of Western African culture, history, and folklore, steeped in the influences of Cartoon Network, anime, and political activism that permeated creator Juni Ba’s young life as a Senegalese boy born and raised in the ’90s.

When we meet the main protagonists, it is a decade after the wizard’s destruction of the world. Mansour Keita has gambled away his family’s armour, and is by no means worthy of the royal lineage handed down to him by the late, great king, his father. When the story begins, we have already moved beyond the feeling sorry for himself part of his journey of personal growth, though the shame of his actions still follows him. He is ready to do what he must do to get his legacy — the armour — back, despite being certain that he will never live up to his father and become the king his people deserve.

Mansour is accompanied by Awa Kouyaté, who serves as his djeli, a royal bard. The term is Malinké. It means “bloodline.” Like the Keita royal bloodline, Awa’s role also comes with great responsibility as the weight of knowledge is passed down through the generations. Other djeli have turned their talents to other uses, like DJing at nightclubs where debauchery runs wild. Rather than counselling, guiding, and educating leaders and their people, these djeli turn to performance and offer favours and moments in the spotlight for a price. Awa abhors the lack of ethics and dedication to the art the other djeli display as she struggles to find the right motivation to bring out the best in Mansour and help him move past his shame.

Where Mansour is determined but uncertain of who he must become, Awa is grounded in the knowledge she has been taught and adamant about clinging to history, despite the vastly different present and future before her.

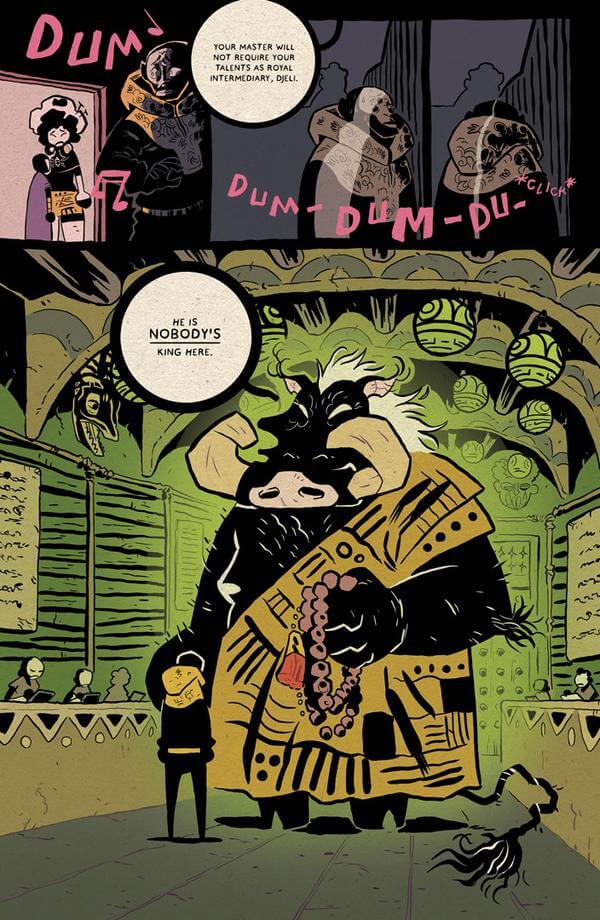

The first task with which they must prove themselves is retrieving Mansour’s armour. To do this, they must do the bidding of Mbam (“pig” in the Wolof language). He is a corrupt holy man whose power and influence are matched only by his desire to discover the secrets of Soumaoro’s ivory tower and seize control of it for himself. Mbam is the first of the anthropomorphized characters we meet, as Ba draws on Western African folklore to shape the story. Symbolism and language play an important role, with words translated along the way, and names and symbols described in a glossary in the back of the book.

Mbam demands that they defeat the crafty Bouki (“hyena”), who leaves a trail of blood behind him and whose power and influence threaten Mbam’s. “You help one criminal kill another, what does that make you?” Awa admonishes, but she has no choice but to follow Mansour on this quest.

It is the first of several quests in their adventure, all of which are brutally violent. Ba’s uniquely stylized imagery softens the blow of the violence somewhat, given that the intended audience is 12 and up. However, the story doesn’t take for granted the maturity of its audience and the reader’s willingness to explore the darker side of folklore, fantasy, and reality, as Djinne, child soldiers, infidelity, and drugs all make their way into the mix. Still, the story is not without a sense of humour, captured through comedic beats in both words and imagery, such as knowing looks, or the sudden appearance of adorable puppies.

The Cartoon Network influences, particularly Genndy Tartakovsky’s work, are clear in Ba’s style, melded with traditional African elements and futuristic vibes. Ba is liberal with his use of full black in linework, shadowing, and fills, contrasted by muted primary colours and warm oranges and browns. The story shifts through its chapters in this way, pausing for a black and white interlude that explores how easily people can be ruled by superstition and mistrust.

The imagery is empowered by the text, which Ba uses masterfully. Sound effects burst from panels and careen across the page. Colour, shape, and line depth give each voice a unique and powerful flow that makes the words practically sing in the reader’s mind.

Where this story truly shines is in its twists and turns. Though Awa and Mansour’s quest seems straightforward and typical, what they learn about themselves and their world as Ba peels away and adds each layer is an astounding feat of storytelling. He also manages to shift seamlessly to a global scale, making it easy to relate his messages and symbolism to any number of the issues we face today in any society.

As his first graphic novel, it is an impressive introduction, showing that Ba’s skill as a storyteller is as clear, colourful, mind-bending, and intricate as Anansi.