Back in September, two trailers came out on the same day, and I tweeted, “Wanda’s thinking of ending things.” It’s a joke that works because in later years Wanda Maximoff, the Scarlet Witch, has been given tremendous reality-adjustment abilities (she could end anything in a blink, including the Mutant Menace), and because the glitchy visuals, the emotional hitches, and haunted dissociation of Charlie Kaufman’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things was reflected in WandaVision’s kitschier style. Existential heterosexuality: that’s The Scarlet Witch all over. And I guess The Vision, too.

There were two limited series/trade collections/thick comic books, material originally published in the ‘80s called “The Vision and the Scarlet Witch.” The first (1982) is largely by Bill Mantlo and Rick Leonardi; the second (1985) is largely by Steve Englehart and Richard Howell. They are very good, and I think should legitimately appeal to a wide swathe of the prospective Wandavision demographic because they are a) superhero comic books with colourful and wild superhero action and b) family-based soap opera melodrama, and c) both at the same time, entirely entwined. They are about two superheroes who fell in love, who wanted a normal married life.

Let me express the core attributes of the characters in the context of these books:

Wanda is an orphan twin, raised by a woman-shaped cow; a Roma child whose father kept being revealed to be somebody new, who is also a mutant, who was also sexually manipulated by a supervillain—who is one of the people who turned out to be her father (at one, or two, points). She is also essentially feminine: all elements of her design and character motifs point to a big sign that says GIRL, THE WOMAN, THE FEMALE ONE, even on teams when she is not the only one. Her costume is pink and red, Valentine’s Day colours; her hair is big and soft and curly. She wears a bustier and opera gloves, and her codename includes the word “witch.” Her story is about being a sister and the girl who dances for the boss and a daughter and a wife—and a mother. Her greatest show of power is the creation of her own spontaneous pregnancy. She picks up clothes her husband leaves on the floor. Naturally one could say “these do not mean the character must be a woman,” because gender is a matter beyond the page, but taking acceptance of Wanda as a woman through these pro-traditional/assumption-enabling coded symbols all amounts to an interesting tumult. She is wholly “feminine,” and a superhero, and does not possess signifiers of dominance.

(It’s not much of a coincidence that the peak period of ultragirl Crystal begins in the second Vision and the Scarlet Witch series.)

The Vision is a synthezoid, which is a “built human,” which some persist in understanding to mean “a metal robot full of circuits.” Within The Vision and the Scarlet Witch, the Vision is not a robot: he is a constructed man, whose form is identical to a traditionally birthed human other than in colour and atomic control. He is very obviously “different” to the normative vision (that’s a pun) of a human, because he is bright literal red, and much of the time extremely deadpan, and can control the density of his own body. He is also a superhero who wears a superhero costume and pretty much only knows other superheroes; he is also the “twin” of Wonder Man, his synthetic body having been given life with the implementation of Wonder Man’s brainwaves after the latter’s (assumed) death. Naturally he suffers from Impostor Syndrome. He also suffers persecution from the birth brother of Wonder Man, who finds him a perverse adulteration of his brother’s memory.

Why might these characters crave to share a template?

Wanda and the Vision fall in love. Her brother doesn’t like it. The couple’s first limited series is about their various wider family issues immediately after they move in together, and the second is about their attempt to retire from Avengers membership, take a little them-time and settle down together, aiming to have babies. As you might expect, they encounter obstacles and assumptions, and their desires for quietude and togetherness are challenged consistently—lampshading, and activating, the innate challenge to that desire. Do you really want to be part of a perfect suburban family? Don’t you really want drama and originality and freedom? Wouldn’t you really enjoy it better if Thanksgiving dinner was interrupted by a supervillain fight instead of just being awkward and rigid because your friends hate your estranged dad? But never do you really yearn for security in love? Do you really want connection with your family? Would anyone really want to walk through a meadow and think about babies? Challenges to desire are lobbied, but mockery of the roots of that desire is not.

There are other markedly feminine superheroines in Marvel’s ’80s, and there are many other superhero romances and melodramas, and there are limited series which shine a spotlight on a character who falls in love, has a brother, a father, etc. But there are none so near to the surface, none so intrinsic to the title as Vision and Scarlet Witch’s. Patsy Walker and Daimon Hellstrom have fun marital problems in The Defenders, but they share the book and their page time with the rest of the team; ditto Scott and Jean, or your fave couple. Even Spider-Man and his girl of the era fall into this, because Spider-Man doesn’t have to be about both Spider-Man and Mary-Jane until the book is called Spider-Man and (or Loves) Mary-Jane; similarly, the TV shows are always called Lois and Clark, or Superman and Lois, instead of just The New Adventures of Superman. When one is working within an already-labelled genre—”Superhero”—romance will always be a sometimes-perk unless romance is promised, in active addition, by the title.

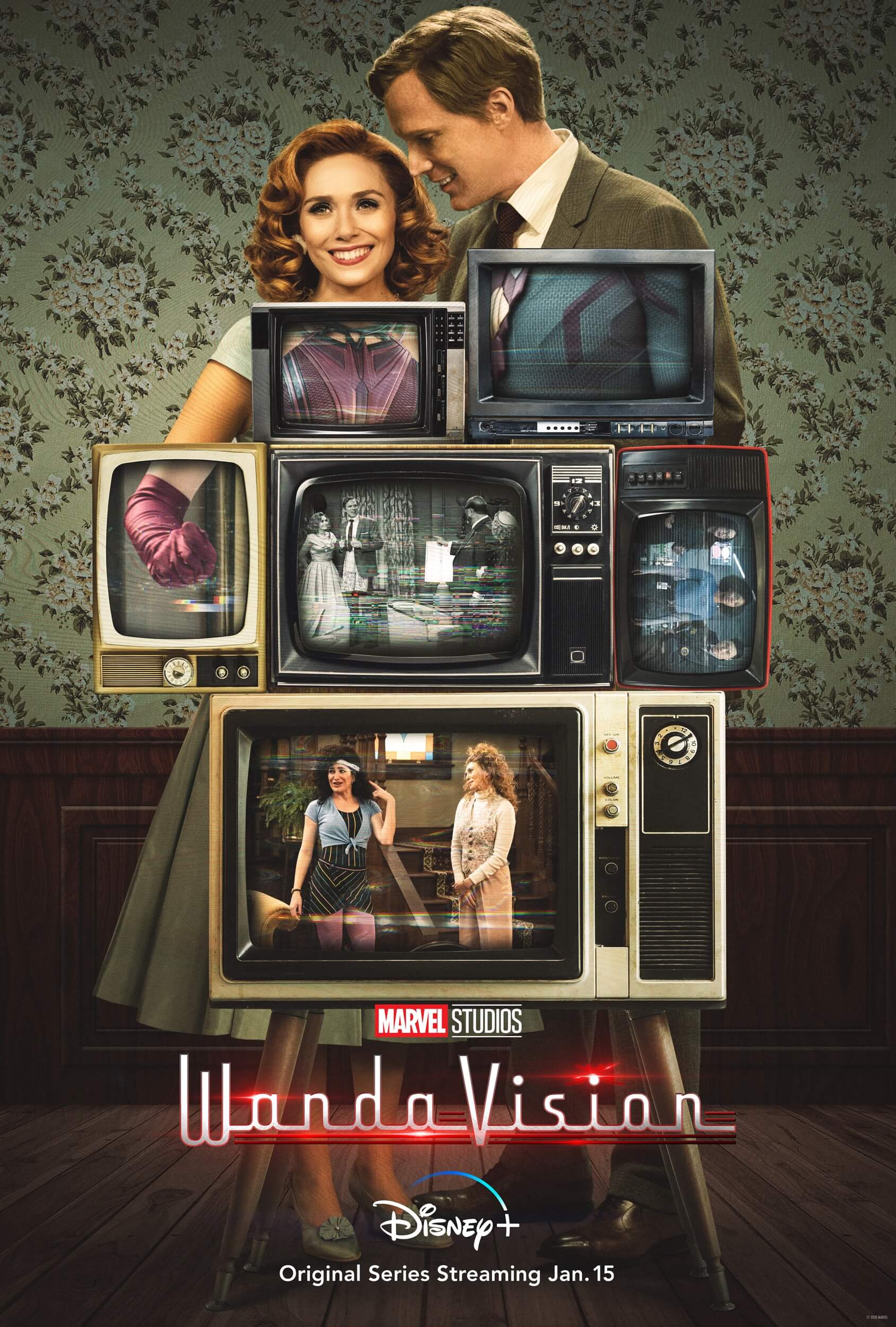

Even the Fantastic Four, where Reed and Sue—an older type of romantic template, who by The Vision and the Scarlet Witch volume one have been established as parents (not nesting newlyweds) for fourteen years—share their platform as a couple with their team members. They are the Fantastic Four, rather than being subjects of a book called The Richards-es who also happen to have good friends and family members around them. The Vision and The Scarlet Witch, in both iterations, emphasises the “and” as the premise just by including it. It claims the vital energy is in their joint status, similar to how classic sitcoms like I Love Lucy or Bewitched situate the pinion of their see-saw inside a marriage. Those shows can be more oblique when they name themselves (just allusions to the men’s perspectives, no “and” necessary) because their primary genre is “marriage story”: comedy is a form of interaction and marriage, a very interactive state, was an expected part of a human male’s life at their time of screening. Like The Vision and The Scarlet Witch, WandaVision lays a claim on togetherness before or concurrent to its claim on the superhero audience.

These older comics aren’t “meta” as WandaVision looks to be, but they’re puckish and delightful in the ways that meta fiction aims to be. The metatextual nature of WandaVision is due to the norms and expectations of our time; it’s the modern element that an adaptation should offer to an older text and that can’t really devalue the lack of itself in that older text. If you read Englehart and think he’s not winking—are you sure? If you like the aesthetic switch-trickery in WandaVision, you’re connecting with the Wanda/Vision premise through today’s evolved multi-retro aesthetic. The comic offers a peep through a time hole, the same root premise and the same root retromantic aesthetic, but through the 1980s lens. They’re both making different flavours of the same joke and the same claim on the relevance of designated-feminine interests—even if its peak soap atmosphere doesn’t appeal to you, experiencing the earlier comics will help you understand or appreciate what and why was made of the later television.

This is a collected volume that contains all of these comics at once.

This is a collection of the first series.

And this is a collected edition of the second series (my fave of the two—so dishy).