“In the world of comic books,” wrote Jack Shaheen, “one is about as likely to find a good Arab as the camel is to pass through the eye of a needle.” Instead, they often appeared as some of the stereotypes in television and film that Shaheen would become known for writing about: terrorists, sinister sheikhs, and bandits. For Arab women, if they appeared at all, there were even fewer roles than for men: either exotic belly dancer or oppressed housewife. Shaheen was writing ten years before 9/11, twenty years before Simon Baz, and almost thirty years before Fadi Fadlalah. Fadlalah (co-created by writer Saladin Ahmed and illustrator Sara Alfageeh) is the first superhero to go by Amulet but not the first Arab or Arab American superhero.

Neither is Baz, the Lebanese American Green Lantern co-created by writer Geoff Johns and artist Doug Mahnke. More than a year before Baz, Algerian French Bilal Asselah first appeared as Nightrunner in a Detective Comics annual. In 2007, five years before Baz, DC revived Golden Age superhero Ibis the Invincible in a one-shot, introducing Egyptian American Danny Khalifa as the inheritor of the Ibistick, which you may have — believe it or not — seen on screen in Shazam! Khalifa is notable if only because his origin story is similar to those of both Simon Baz and Doctor Fate’s Khalid Nassour, who debuted in 2015.

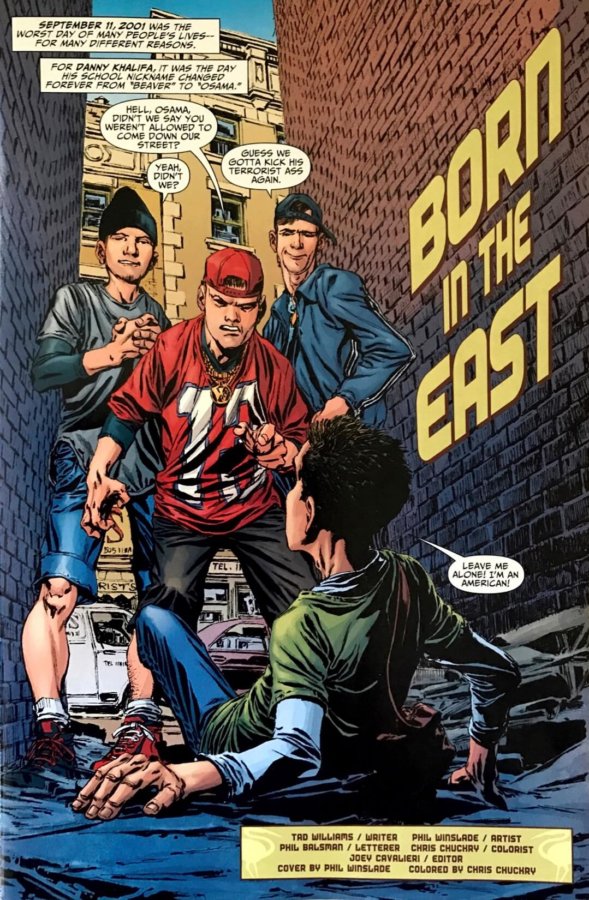

Danny Khalifa’s story begins with 9/11. Writer Tad Williams, artist Phil Winslade, colorist Chris Chuckry, and letterer Phil Balsman’s The Helmet of Fate: Ibis the Invincible #1 opens with Khalifa being assaulted by white boys who hurl slurs at him. There is a certain irony in the fact that the creative team mirrors the boys: white men using words that do not affect them.

They also make it clear that Khalifa is Egyptian, going so far as to imply that he is descended from royalty. This allows them to draw connections to ancient Egypt, which given Khalifa’s Arabic surname is tenuous at best, racist at worst. Like later attempts to repatriate fictional Egyptian artifacts to Arab Americans (namely Doctor Fate), this narrative conflates ancient Egyptians and modern Arabs, as if the latter were not living people but mummies, preserved not by science but by magic. Magic is what brings Khalifa to the first Ibis, Amentep, who he is called to mummify. As the story progresses, Khalifa faces off against Egyptian gods and, in doing so, earns the right to call himself Ibis. It is an early, well intentioned if poorly executed, attempt by mainstream comics to tell an Arab American story after 9/11.

Set in Dearborn, Michigan (the Arab capital of North America), Simon Baz’s story (written by Johns, pencilled by Mahnke, inked by Christian Alamy, Keith Campagne, and Mark Irwin, and colored by Tony Avina and Alex Sinclair) also starts with 9/11. In Green Lantern #0, Baz, appearing as a child, sits with his family, watching the terrorist attacks in New York on a television screen.

His mother wears a hijab, signaling to the reader that the family is Muslim, putting them in a minority of not just Americans but also of Arab Americans. Most are, like Baz, Lebanese (or from the greater Levant: Jordan, Palestine, and Syria) and, unlike Baz, Christian. Geoff Johns, Baz’s co-creator, is Lebanese but not Muslim, like me. Like Khalifa, Baz was created to take up an existing mantle, inheriting a Green Lantern ring from Hal Jordan and Sinestro. As the story progresses, he eventually fights against the Third Army, which intends to assimilate him, something the comic is already doing (or, at least, trying to do) by making an Arab man into an American superhero.

Green Lantern advances a long tradition of superhero comic books making Americans out of aliens, which began in 1938 with Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman and continues into Ms. Marvel, the first mainstream superhero comic book to feature a Muslim woman as the title character.

And the first comic book that I read monthly, starting my last semester of college. As an Arab American reader, the Pakistani American Kamala Khan seemed the closest I could get to seeing myself represented in a medium that I didn’t yet know a lot about. My digital subscription to Wilson and Alphona’s Ms. Marvel (2014-2015) followed me from Tallahassee, Florida, to Charlottesville, Virginia, where, two years after completing my bachelor’s degree, I would earn my master’s having written my thesis, “The ‘Embiggening’: Marvel’s Muslim Ms. Marvel and American Myth.” I started thinking about all of the ways in which this new character was new and all of the ways she wasn’t. Most of how Khan can be described — a teenage, Pakistani, Muslim superheroine — could be applied individually to other characters— Peter Parker, Faiza Hussain, Sooraya Qadir, Carol Danvers — and while I wouldn’t describe her as such, Khan has been called the next Spider-Man (it feels like it should be more difficult to say that after Into the Spider-Verse, which introduced a more fully realized Miles Morales, or before she’s been written by a Muslim woman of color). I’ve always seen her more as a modern Superman.

Meanwhile, on the heels of Kamala Khan, DC introduced a modern Doctor Fate. Co-created by writer Paul Levitz and artist Sonny Liew, and introduced somewhere between the New 52 and Rebirth, Nassour was the second Egyptian to don the Helmet of Fate (the first, also named Khalid, would appear in an alternate universe a few years before). However, in the eighteen issues of Doctor Fate (2015-2016) in which he appears, the Egyptian American Nassour is never once called Doctor Fate.

Those eighteen issues, which span — at most — a few weeks, see Nassour enter medical school and very nearly flunk out as he tries to figure out how to be Fate, something which is due to him by blood: that of his Arab father and their pharaonic forefathers. Again, ancient Egypt and modern Egypt are collapsed onto one another, even as the comic served as a reaction to the Arab Spring. American superhero comics have demonstrated a fascination with ancient Egyptian culture since the 1940s, following decades of American popular culture doing the same: King Tut’s tomb was opened in 1922, The Mummy followed in 1932, then Kent Nelson as Doctor Fate in 1940. Seventy-five years later, it should not be so difficult to imagine that a modern Arab hero would not be the blood of the pharaohs but any one of the millions protesting.

Like any one of those currently demonstrating in Lebanon. In October of 2019, millions of Lebanese citizens took to the streets in protest. Two months later, Marvel would announce its first Arab American superhero: the Lebanese American Fadi Fadlalah. Fadlalah, or Amulet, will debut in Magnificent Ms. Marvel, the most recent iteration of the book that brought me to comics, written by the character’s co-creator, Lebanese American writer Saladin Ahmed.

I had the privilege of meeting Ahmed in 2018, a little less than a year after he had started writing for Marvel. He was in Virginia to give a talk on Frankenstein — a book that I still have not read — for its 200th anniversary. You can watch it on YouTube.

I drove to Farmville from Williamsburg, where I had just a few months before started my Ph.D. program, skipping–with permission–a Monday night seminar. The weekend before the talk, Ahmed did a Twitter Q&A, and he answered my question, “Would you ever write an Arab/Arab American superhero?” with, “Most def. Very consciously saving that for when I have muscle/space to focus and do something big & lasting.” In retrospect, it’s hard not to take “something big” literally.

Fadlalah, designed by Jordanian American illustrator Sara Alfageeh, is big. “This character,” to quote Alfageeh, “is a gentle giant, so I wanted to make sure that even with his size he was shaped like a friend!” Like Khan, this character is new and different, but not all-new or all-different. Like Baz, Fadlalah is Lebanese American. He’s also from Dearborn. However, apart from those two things, neither of which is entirely unusual for Arab Americans, they don’t seem to have all that much in common. Baz’s design is much like that of 90s superheroes–all muscle–and he’s not gentle. Fadlalah is also younger, figuring in to Marvel’s forthcoming Outlawed event concerning teenage superheroes, which makes him younger than Nassour, whose design is even more radically different from that of Fadlalah. Nassour is thin, almost lanky, with stereotypical features. The idea of an Arab superhero who is allowed to both take up space and be soft is one that makes Fadlalah a welcome addition to the ranks of comic book Arabs. So, too, is his name: Amulet.

?I am THRILLED to introduce you all to Marvel's newest superhero, the mystical defender Amulet.?

He's Arab American from Dearborn, Michigan and was created by myself and @SaraAlfageeh! https://t.co/EomfqFtoru pic.twitter.com/q4iZ62BFBZ

— Saladin Ahmed (@saladinahmed) December 18, 2019

Unlike Nassour, Baz, or Khalifa, Fadlalah originates his superhero name. Rather than try to fit an Arab American character into a role designed for someone else, which isn’t necessarily bad or good but reflective of the ways in which minoritized characters have often been slotted into pre-existing roles, Fadlalah is the first of his name. There is an opportunity, in that, to challenge the ways in which the superhero genre has functioned as a means of assimilation and, further, to break away from the stereotypes by which Arabs in comic books and other popular media have so long been defined. At least, Arab men. As excited as I am to see Amulet debut, I can’t help but think about how much more excited I’d have been to see a character even more like me, which isn’t a criticism of the character or his creators as much as it is a critique of the systemic erasure of Arab women, who are rendered invisible in their absence.

Still, I am excited because this means I get to do what I told Saladin Ahmed I would when I met him: write about his work. By the time Amulet debuts in March, I’ll be working on my dissertation on Arab and Muslim superheroes, of which there are more now than ten, twenty, or thirty years ago.