The period following the publication of Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire saw vampire fiction entrench itself not as a subgenre of horror, but as a substantial body of fiction in its own right. Author David J. Schow would look back on this state of affairs in his 2018 collection DJStories:

You know how zombie-flavoured everything seems chokingly omnipresent? Well, that’s how the late 1980s flood of vampire fiction used to be. Mysterious Bookshop in Los Angeles had a vampire “dump” bin (cardboard rack of 12 paperbacks) that refreshed every week. Twelve new vampire-themed books per week.

All of this coincided with a cultural embracing of the vampire as a sympathetic figure, something that spread from literature to cinema. Films like Lost Boys (1987) and Near Dark (1988) portrayed vampires as leather-clad gang members, ensuring that they retained a degree of countercultural coolness even when cast as villains. Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 Dracula film, although purporting to be a faithful adaptation of the novel, gave the Count a whole new motivation and character arc, turning him into a tragic villain in search of his lost love. The 1994 film version of Interview with a Vampire further cemented the idea of the vampire as at least partly sympathetic. Then in 1997 came the debut of television’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer, in which vampires ended up as disposable cannon fodder for a wisecracking teenager (whose superheroic exploits owed more to Stan Lee than to Bram Stoker). Meanwhile, thanks to role-playing game Vampire: the Masquerade that made its debut in 1991, fans could even turn themselves into vampires.

Even leaving aside the outright parodies like Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995), it was clear that vampires could not be counted upon to be scary anymore. This was no problem, thanks in large part to the emergence of a significant commercial genre during the close of the twentieth century: urban fantasy.

1989: The Vampire as Punk

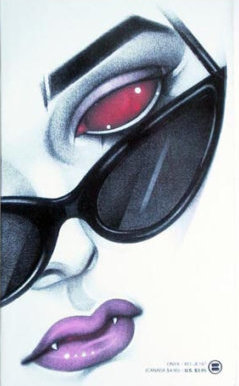

The eighties saw a variety of vampire series competing for shelf space, as the continuing exploits of Anne Rice’s Lestat occurred alongside Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s tales of Count Saint-Germain (beginning in 1978 with Hotel Transylvania) and Brian Lumley’s vampire-hunting hero Harry Keogh (debuting in 1986’s Necroscope). But perhaps the hippest vampire protagonist of the lot was one who made her fashionably late arrival at the decade’s close: Sonja Blue, created by Nancy A. Collins. Sonja first appeared in the 1989 novel Sunglasses After Dark, which gave rise to two sequels in the nineties, two more in the twenty-first century, a smattering of short stories and a stylish comic adaptation illustrated by Stanley Shaw.

Sunglasses After Dark opens with Sonja in a straightjacket as a patient at a private asylum. After she fights her way out, she sets off to confront the woman responsible for her plight: a television preacher with the unlikely name of Catherine Wheele. As we see in a series of extended flashbacks, Sonja was once a teenage socialite named Denise Thorne, whose life of affluence and privilege came to an end after an encounter with a vampire named Sir Morgan; if she is to succeed in her battle against Wheele, she must sever her remaining ties to this old persona – while also grappling with a murderous alter-ego that she comes to know as the Other.

Interview with a Vampire began its story in the eighteenth century, but Sunglasses after Dark has no interest in such period settings. Instead, Denise Thorne’s death occurs in 1969 – just twenty years before the book was published, and appropriately coinciding with the end of the peace-and-love decade. Fittingly, Sonja’s subsequent exploits take her through the eras of punk, post-punk, and eventually into the dawn of grunge – as emblemised by the flannel shirt and grubby workpants that she dons after escaping the asylum. As befits this backdrop, her adventures have a down-and-dirty aspect that is a long way from the clean cravats of Anne Rice’s vampires.

In Sunglasses After Dark, vampirism is not used as a analogy for sexual violence, as it often was in the vampire literature of earlier eras, but as an adjunct to it. When Sir Morgan turns Denise into a vampire, it is a literal as well as figurative rape, the forced sex described in harrowing detail. “Everything that was Denise Thorne disappeared, raped into oblivion by her demon prince”, we are told once the ordeal is over. Sonja is then sent through the underbelly of London, where she is passed between pimps and predators; for some time, the closest thing to a decent man she encounters is her boyfriend Chaz, a telepathic drug dealer.

But Sonja’s vampiric abilities lend her a method of fighting back. Exploration of trauma blurs into superhero origin story as Sonja goes to war, first against the mundane abusers on the streets, and then – after she is trained by the Van Helsing-like scholar Ghilardi – against supernatural menaces. “Socialite, hooker, vampire hunter, and vampire – no one could accuse me of leading dull life” says Sonja in one of her intermittent first-person sequences.

Having created her anti-heroine, Collins provides the perfect counterpoint as a villain. Catherine Wheele is a wealthy con artist, masquerading as a pious Christian so that she can fleece her followers using mind-control abilities: a smooth faker to contrast with the streetwise protagonist; a heartless saint to battle the monster-with-a-conscience. Wheele has a traumatic backstory that in some ways parallels that of Sonja — both having abusive father-figures – and in other ways inverts it. Where Sonja plummeted from affluence to squalor, Wheele was born into poverty before using her gifts to cheat her way upwards.

The vampire Sonja and psychic Wheele are not the only supernatural denizens of Sunglasses After Dark’s urban milieu. A zombie-like vampire subclass turns up, as in Interview with a Vampire, but so do werewolves, ogres and even angels. These beings live amongst humanity in disguise: “To the humans it is just a bag lady, another bastard child of Reaganomics. But I see the seams in the costume and the stage makeup on its face. It is a seraph, come for a brief visit.”

The idea that modern cities are rife with all varieties of supernatural being, that sundry monsters of folklore, legend and modern pop culture are secretly next door to us, would become a defining element of the urban fantasy genre.

1991: The Vampire as Detective

Vampire fiction of the 1990s was a broad church indeed, including as it did the Gothic homoeroticism of Poppy Z Brite’s Lost Souls (1992), the metafiction of Kim Newman’s Anno Dracula (1992) and the psychosexual surrealism of Charlee Jacob’s This Symbiotic Fascination (1997). But it seems likely that (as far as vampires are concerned) the decade will be best remembered as the time at which urban fantasy began to flourish as a commercial genre – and one of the earliest authors to see this genre’s potential was Tanya Huff, who turned to the vampire theme in her 1991 novel Blood Price.

In her introduction to the 2006 omnibus of Blood Price and its sequel Blood Trail (1992), Huff describes how the idea for the novel came to her while working at a Toronto bookstore in 1989:

I noticed that vampire readers are very loyal. In a desperate search for something decent to read they’ll cross their fingers and pick up just about anything with fangs on the cover. We were thinking of buying a house in the country and so would need a mortgage and vampire books came with a large—and, as I mentioned, loyal—fanbase built in.

Huff had already explored urban fantasy in her 1989 novel Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light, which depicted a battle between good and evil magic in the streets of Toronto. Initially struggling with her commercially-minded decision to try out the vampire genre, Huff eventually decided to return to her past approach:

So I wrote the first chapter of my “vampire book” and it just wasn’t working. The beloved read it and said, “You know, instead of writing a vampire book, why don’t you write a Tanya Huff book with a vampire in it.” And so that’s what I did.

The main character of Blood Price is private detective Vicki Nelson, who finds herself faced with a series of murders. While investigating, she is startled to discover that she shares a city with a vampire named Henry Fitzroy — known to history as the illegitimate son of Henry VIII. At first she believes that she has found the killer; but in reality Henry is a comparatively harmless vampire, more interested in writing romance novels than biting necks.

If the vampire is not responsible for the murders, then who is? Vicki and Henry team up and eventually track down the true culprit: Norman Birdwell, a nerdy college student who, having been rejected by a string of women, took desperate measures to obtain his revenge: he has summoned a demon to slay every woman who turned him down.

In terms of overall narrative structure, Blood Price is a conventional detective novel. It has a straightforward detective protagonist, and a villain who – despite his supernatural modus operandi – has an ultimately mundane motive. Huff’s method of reconciling her crime narrative with its supernatural aspects is more literal-minded than that of Collins, but still effective: as a detective novel, Blood Price is a story of law and order; and so the beings that inhabit its supernatural Toronto are given sets of rules to follow. The more rule-bound a creature is, the more it can be trusted.

Henry Fitzroy, as a vampire, is the natural choice for good-guy monster as every reader will know that vampires are bound by a familiar set of rules involving sunlight, garlic and so forth. While Henry’s early exchanges with Vicki confirm that not all of these rules are valid (he is able to enter homes without invitation, for example) even these points serve lay out exactly what Henry is, and is not, capable of doing; his supernatural nature can be easily grasped by the reader.

The demon summoned by Norman is different in that, while it has a set of rules of its own, it is prone to finding loopholes. At one point Norman tries to send it to kill a particular woman but – as he does not know her name – he hands one of her gloves to the demon, asking it to kill the woman who has the other glove. By that point, the other glove has been picked up by someone else – who becomes the demon’s next victim instead. If the vampire and the demon exist on different tiers, yet another tier becomes apparent when it turns out that Norman’s demon is attempting to enlist the help of a Demon Lord: something genuinely intangible and unknowable, playing by rules that are its and its alone. “This is demon lore”, says Henry. “There aren’t any cut and dried answers. Experts in the field tend to die young”.

Although Blood Price casts the vampire as a relatively benign member of the monster pantheon, Henry Fitzroy is not entirely defanged. At the climax to the novel Vicki allows Henry to heal himself by feeding from her, a scene that embraces the erotic aspects of vampire literature: “She could see why so many stories of vampires tied the blood to sex—this was one of the most intimate actions she’d ever been a part of… He could feel the life that supplied the blood now. Smell it, hear it, recognize it, and he fought the red haze that said that life should be his.”

Having laid out the basics of her urban fantasy setting with Blood Price, Huff explored further across a string of sequels. The first, Blood Trail, adds werewolves to the mix but chooses a pair of villains who are all too human: one hunts innocent werewolves out of religious fanaticism, the other does so in pursuit of their luxurious pelts. But the legacy of Blood Price extends beyond Huff’s own writing Seanan McGuire, whose own work is influenced by Huff, cites Blood Price as the starting point of urban fantasy as a genre:

Do you think she just woke up one day and said “I think I’ll create a genre?” Blood Price was really the moment where you could see the urban fantasy genre start to turn from something that sort of skulked around the edges of the high fantasy into a fully-fledged, fully-functional genre in its own right. Engaging story, awesome characters, top-notch writing, Blood Price had it all. Still does. You want to see where the genre started, this is the place to go.

Certainly, reading Blood Price today, it is easy to see the book as a template for much of the urban fantasy to follow. Even the pairing of Vicki Nelson and Henry Fitzroy echoed down the line, with numerous urban fantasies starring a partnership between a supernatural male character and a female detective or police officer; examples include Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files series (beginning with Storm Front in 2000) and TV shows like Gargoyles (1994-7), Angel (1999-2004) and Sleepy Hollow (2013-7).

The formula of supernatural man meeting mortal woman also leads us to a genre that closely overlaps with urban fantasy: paranormal romance. And it is in paranormal romance that we find what must surely be the most influential – and also most controversial – vampire story of the twenty-first century thus far…

2005: The Vampire as Boyfriend

Every so often, there comes along a novel that impacts its entire genre. Some authors will imitate it, while others will self-consciously avoid comparisons with it – but either way, they will have been influenced by it. Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight, published in 2005, is one of those novels. It ensured that, for subsequent generations, vampire fiction could be roughly divided into two categories: like Twilight, and not like Twilight.

The plot revolves around teenager Bella Swan, who moves to the Washington town of Forks and enrols in the local school where she meets Edward Cullen and his family. After the alluring and mysterious Edward saves Bella’s life from a traffic accident using superhuman abilities, he admits that he and the other Cullens are vampires. This, however, does not prevent Bella from pursuing a romantic relationship with the undead dreamboy.

Despite finding great popularity with its target demographic, Twilight earned a place in the popular consciousness as the book that defanged vampires. It achieved particular infamy for introducing the idea that vampires sparkle in daylight – although, in fairness, this arises more from the questionable special effects of the film version. In the novel, the characteristic is a fairly imaginative addition to the vampire mythos that receives a logical explanation (vampires shimmer so as to attract prey, rather like an angler fish’s lure) and is described in reasonably effective terms. Nor, indeed, are the novel’s vampires entirely bloodless.

A major aspect of Edward’s character is his urge to feed on Bella, which he agonises over as he forces himself to keep it in check. “It’s not only your company I crave”, he says; “Never forget I am more dangerous to you than I am to anyone else.” At one point he compares himself to a recovering alcoholic who can resist stale beer, but who – after meeting Bella – is now confronted with the aroma of “the rarest, finest cognac”. The story also includes vampires of a more conventionally menacing sort, when Edward must defend Bella from a gang of sadistic hunters; in a variation on the white hat/black hat convention of old Westerns, the two stripes of vampire are distinguished by eye colour: golden yellow for good vampires, red for the villains. But despite all of this, it is hard to deny that the novel offers a fundamentally suburbanised vision of vampiredom.

The idea of vampires secretly living among us has obvious potential for humour, hence why many of the best-known treatments of the premise have been comedies – television’s The Munsters (1964-6) being one of many examples. Because of this, any writer exploring the idea in a non-comedic context will be faced with what might be termed the Munsters factor: the inherent silliness of the vampires-among-us concept.

Different writers have come up with different ways of coping with this. In Interview with the Vampire, Anne Rice dodges the issue by using the modern-day sequences merely as a framing device for a series of period pieces written with old-fashioned formality. In Sunglasses After Dark, any humour becomes part of Nancy Collins’ punkish authorial voice, a sarcastic smirk never far from the narrator’s lips. And in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Joss Whedon’s self-referential humour is all part of the appeal.

But Twilight shows no awareness whatsoever that the Munsters factor is even a problem. There appears to be no conscious irony or humour when Bella enthuses over the fact that her new vampire friends drive a cool car; instead, the vampires are portrayed as being almost as natural a facet of the novel’s suburban setting as the corner shop or high school.

Edward Cullen marks an additional stage in what had become a rather convoluted evolution for vampires. John Polidori caricatured Lord Byron to create the archetypal vampire, the dark but fascinating man whom younger men look up to – and women give their lives to. Bram Stoker warped this figure into an aged, henpecked predator. Anne Rice reinvented him as a queer rebel, less Lord Byron and more Oscar Wilde. Then, in Stephenie Meyer’s hands, the Byronic vampire became a well-meaning smalltown boy who simply needed to keep his hormones in check.

But Meyer’s target audience cared little about how Edward matched up with previous iterations of this literary archetype: they merely wanted an escapist romance with a touch of the macabre, and Twilight catered to this desire. The novel was a runaway success, prompting Meyer to write sequels that expanded her world (the most notable addition being, inevitably, werewolves) and inspire sundry other writers to get in on the paranormal romance action.

While detractors may have hailed Twilight as the last gleaming of vampire fiction, the reality is that the genre continued to flourish in the following decade. The final post in this series will take a look at the many varieties of vampire to haunt the pages (and MOBI files) of books published during the 2010s…