In 1977, the British press reports an outbreak of alleged poltergeist phenomena that occurred in the Enfield home of single mother Peggy Hodgson and her four children Janet, Margaret, Johnny and Billy. Claims of strange activity at the house continued until 1979, and the case of the Enfield poltergeist has provoked heated debate ever since. If it was a hoax, however, then those responsible deserve credit for making a durable contribution to popular culture, as the Enfield affair had a significant impact on horror fiction.

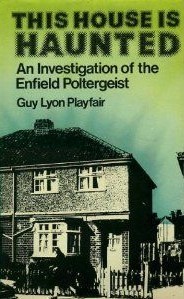

Guy Lyon Playfair – who, alongside colleague Maurice Grosse, was a key investigator at Enfield — wrote about the case in his 1980 book This House is Haunted: An Investigation of the Enfield Poltergeist. The book describes some of the phenomena that allegedly happened at the house: a partial list includes objects flying across the room or appearing in mid-air; paper notes with such phrases as “CAN I HAVE A TEA BAG?” being found around the home; Janet being flung through her bed at night, or even teleported through a wall; and a curtain wrapping itself around Janet’s neck as though trying to strangle her, with a cable and bedsheet later behaving in a similar manner. In addition to the poltergeist phenomena, multiple witnesses reported sightings of apparitions including an elderly woman, a floating child, a doppelganger of Maurice Grosse and — the most common apparition of all – an old man sitting in a chair.

Janet, eleven years old at the time the phenomena started, was at the centre of much of the activity, fulfilling the role of the poltergeist girl. She would apparently enter trances, sleepwalk, and speak in a gruff, masculine voice (as, to a lesser extent, did Margaret). Clips of Maurice Grosse’s interview with Janet’s ghostly alter ego are favourites for documentaries on paranormal phenomena, achieving a degree of iconic status even before the events were adapted for fiction.

Sceptics have argued that Janet could have achieved the purportedly supernatural voice by using her false vocal chords — a point also made about the demonic speech in the Anneliese Michel case. Reading the transcriptions in Playfair’s book, it is easy to be reminded of Philip C. Almond’s observation about possession as an excuse for anti-authoritarian behaviour, as mentioned in part one of this series: the voice says “fuck” and “shit” a lot, calls for jazz music to be played, asks why girls have periods and announces a desire to eat all the chocolates on Christmas, all behaviour that might be expected from a cheeky eleven-year-old.

Grosse and Playfair, however, remained adamant that the phenomena would have been hard to fake. “We taped Janet’s mouth several times, we filled it with water, and we even tied her scarf tightly around her head while she was wearing her tooth brace”, says Playfair in his book. “None of this stopped the Voice though it certainly made things difficult for it.”

Speculation abounded as to where the spirit, if spirit it was, originated. Mrs. Hodgson suggested that the haunting might be related to the family inheriting furniture from a neighbourhood man who had suffocated his four-year-old daughter before committing suicide. A pair of mediums, Annie and George Shaw, visited the house and claimed to make contact with two spirits: a female elemental named Elvie that was being controlled by “a sort of black magic chap” called Gozer or Gober. Two visiting Brazilian Spiritualists claimed that the house was troubled by “a cruel and wanton woman who caused suffering to families of yeomen” in the Middle Ages, prompting her deceased victims to “come back now to get even with her”. Meanwhile, medium Gerry Sherrick identified “an old hag from Spitalfields market” as haunting the house. Other suspects include Frank Watson, a previous resident who had died in the house. After the family made this connection, the gruff voice coming from Janet’s mouth began identifying itself as Joe Watson (Playfair uses pseudonyms in his book, and it is not clear whether the naming discrepancy between “Frank Watson” and “Joe Watson” arose from this practice). To confuse things further, the ghostly voice later started identifying itself as a man named Bill Hobbs who died of a haemorrhage, and claimed to own a dog named Gober the Ghost. At other times it purported to be Fred Nottingham, the deceased father of neighbour Vic Nottingham.

The press inevitably compared the case to popular horror cinema. The Daily Express ran a report by Richard Grant, which was illustrated with a still from The Exorcist showing Regan; Playfair, describing the article, remarked that Regan “looked alarmingly like Janet and I hoped the resemblances between the two cases ended there.” However, he did note that the Enfield affair, like the phenomena in The Exorcist, may have been triggered through the use of a Ouija board:

[Margaret] mentioned one day that one of the apparitions she claimed to have seen was one that she had seen four years previously. She and some school friends, she told me, had been playing around with a Ouija board in a shed. […] I took this opportunity to ask if she had read The Exorcist, or seen either of the films based on it. She said she had not, and did not seem interested.

Various aspects of the Enfield haunting worked themselves into fiction over the following years. The antagonist in Ghostbusters (1984) was named Gozer after one of the Enfield entities, and it is possible that — as Playfair suggests in the 2011 edition of his book — Poltergeist took some inspiration from the case. But the first full-length fictionalisation of the Enfield poltergeist did not occur until 1992, with the 90-minute BBC TV drama Ghostwatch.

Fact and Fakery: Ghostwatch

A close cousin to found footage horror films like The Blair Witch Project (1999), Ghostwatch is the story of a TV crew who investigate a haunted house and find more than they bargained for. The drama cuts between in-studio segments (hosted by real-life TV presenter Michael Parkinson) and on-site footage of the house, each designed to be as authentic as possible: in the spirit of the notorious 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast, Ghostwatch was conceived to trick those watching the original Halloween broadcast into thinking that what they were seeing might perhaps have been occurring for real.

Although a work of fiction, Ghostwatch draws heavily upon the Enfield poltergeist for inspiration. The haunted house of Foxhill Drive, located in Northolt, is home to daughter Suzanne Early and her single mother Pam, clear counterparts to Janet Hodgson and her mother Peggy — although the other Hodgson children are conflated into a single character, Suzanne’s little sister Kim. The faux-documentary structure leads to much of the ghostly phenomena being described in past tense rather than shown; through its first half Ghostwatch offers a sort of highlight reel of the Enfield happenings: we see a photograph of a flying pillow, recalling similar photographs from Enfield; we hear a tape recording of Suzanne speaking in a guttural male voice, clearly based upon Janet Hodgson’s vocal transformations; and we see a schoolbook belonging to Suzanne that has been filled with (illegible, but implicitly obscene) writing and crude artwork, which she denies having created herself.

This last element is a good example of how horror fiction has crept into the purportedly genuine phenomena of the Enfield case. In his book, Playfair describes Janet drawing unpleasant pictures while in some sort of trance:

That morning, Janet… began to draw while still not fully conscious, according to her mother. She was quite peaceful, Mrs. [Hodgson] told me, but not quite ‘with us’. She just took a pad of paper and some felt-tipped pens and drew nine drawings at great speed, giving the impression she was not consciously aware of what she was doing. The drawings were not very nice. The first was of a woman with blood pouring out of her throat… The blood was slashed onto the paper in red ink. The others were all on the theme of blood, knives and death, one just consisting of the word BLOOD written several times over the page.

But with the drawing in Ghostwatch, blood is only part of the story. The picture, briefly glimpsed before the camera, shows a crude outline of a crucified figure, bleeding from the hands and sporting a large penis between the legs. This blasphemous image recalls an early scene in The Exorcist, where a church has been desecrated so that a statue of the Virgin Mary has large, horn-like structures — resembling Regan’s art and craft projects – adorning its breasts and crotch.

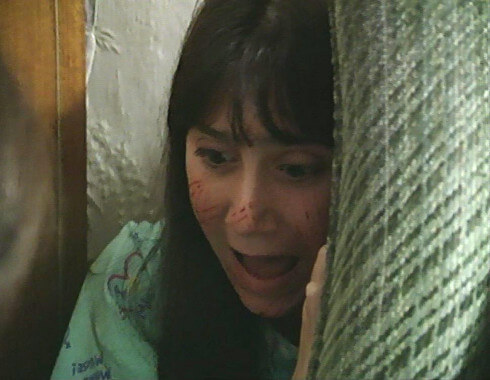

After the drama’s halfway mark, the spirit begins acting up before the camera. We see a sort of “Exorcist-light” sequence where Suzanne lies in bed breaking into short convulsions, scratches resembling the claw marks of a cat all over her face; although less spectacular than Regan’s ordeal, the format of the drama lends greater verisimilitude. We glimpse a ghostly figure standing behind a door, and a technician is seen injured — possibly dead — with a shard of glass in his head. Like most of the better found footage horror, Ghostwatch embraces the ambiguity and subjectivity of its format: it is never entirely clear what is happening in the story’s final minutes, but it is safe to say that the ghost has come out on top. The actual conclusion of the Enfield affair, with the phenomena simply fading away over time, would never have made for a dramatic climax.

From a narrative standpoint, another frustrating aspect of the Enfield case is the contradictory evidence as to who the ghost was when alive. Ghostwatch replicates this to a certain extent, with characters offering multiple stories to explain the ghost’s identity. One caller claims that the area was once home to a nineteenth-century woman named Mother Seddon who drowned babies; but the account that is foregrounded by the drama comes near the end. Michael Parkinson receives a call from a man purporting to be a social worker who knew a former resident of the Foxhill Drive house. Named Raymond Tunstall, the resident lived a depraved life before committing suicide, after which his body was eaten by his twelve pet cats:

When he came out of psychiatric hospital, he had several convictions for molestation, aggravated abuse, abduction of minors. He should never have been let anywhere near the community. He was a very disturbed man in my opinion. From the time he moved to Foxhill Drive, he developed paranoid fantasies. He used to tell me there was a woman on the inside of his body, taking over his thoughts and actions, making him do things he didn’t want to do. He started wearing dresses. The delusions got so bad, there was only one way to escape them. He took his own life.

The character of Raymond Tunstall appears to have been pieced together from elements from various horror films. The association between gender nonconformity and criminal insanity had previously been embodied by Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) and Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), while the plot element of a deceased child-molester returning as a malevolent ghost — like a communal memory that will not stay repressed — recalls A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and its sequels.

To incorporate the Tunstall revelation into the haunting, Ghostwatch introduces a few elements with no basis in the Enfield case. Multiple witnesses describe the apparition of a ghoulish man in a dress, and the ghost’s presence in the climax is heralded by the yowling of unseen cats. But on a deeper level, the revelation affects the character of the spirit and — by extension — the story. Given that the house is haunted by the ghost of a child molester, Suzanne’s anguished moans of “he’s touching me, he’s hurting me” have unmistakably paedophilic implications. To fuel its climactic scares, Ghostwatch ends up moving away from the ambiguity of the Enfield haunting and towards a form of evil that is all too genuine.

Maurice Grosse, who had limited involvement with Ghostwatch in helping the producer to find possible contacts for unscripted interview segments about the paranormal, was not pleased with the results. He gave his thoughts in the winter 1993 edition of the Society for Psychical Research newsletter The Psi Researcher:

I was certainly unhappy to discover that sections of it were unashamedly appropriated from the Enfield Poltergeist Case. Even the voice recordings of the “poltergeist” were a thinly-disguised paraphrase of my recordings of the real voice experienced at Enfield. When I tackled both the producer and the author on this plagiarism, I was met [with] sheepish grins, certainly no denial. The researcher was more forthcoming on this point. She had previously agreed that the Enfield case was the role model. This was certainly true of the first part of the film, until the whole thing eventually turned into a chaotic farce. This latter nonsense must have given viewers the impression that poltergeists are evil and demonic. In my experience, which is quite extensive, this is not so. The events are more mischievous than evil.

This controversy was re-ignited following Playfair’s death in 2018, prompting Ghostwatch writer Stephen Volk to defend himself in the January 2019 issue of the Fortean Times:

We didn’t tell Guy we were “ripping off” his book because in my opinion, we weren’t. […] I’m happy for the public to make up their own minds about the Ghostwatch/Enfield question. Guy Playfair, in the end, was too. I greatly respected him and his work, and he knew that.

Viewing Ghostwatch in relation to the Enfield case, it is hard to deny that the latter was a key influence on Volk’s story. But then, the Enfield case itself often resembles incidents in The Exorcist. Volk’s re-interpretation of the narrative involved pushing it further into Exorcist territory, with the poltergeist becoming — as Grosse noted — “evil and demonic” rather than merely prankish. The real-life exorcism in 1949, the plot of The Exorcist, the Enfield affair and Ghostwatch reflect one another like a row of mirrors –and further dramatisations of the Enfield narrative would merely add more mirrors to the row.

Father and Daughter: The Enfield Haunting

More than a decade after Ghostwatch came the three-part Sky Living miniseries The Enfield Haunting (2015), which credits Playfair’s book as its source material (although he came to criticise the final production in the July 2015 Fortean Times). Slick and sensationalized, The Enfield Haunting presents the phenomena as being unambiguously real, and is not above embroidering the facts of the case.

The characters include fictionalized versions of both Maurice Grosse and Guy Lyon Playfair, the story using them to articulate themes of belief and doubt. The two are initially presented as rivals: Grosse is convinced that the poltergeist is genuine, but his younger partner Playfair is sceptical. Even after encountering the ghost head-on, Playfair continues to clash with Grosse, insisting on a higher standard of evidence. While Playfair remains clean-cut and confident, Grosse becomes increasingly shaken. He is affected not only by the events in the haunted house, but also by the recent loss of his daughter — who, like the girl at the centre of the Enfield phenomena, was named Janet.

In reality, Maurice Grosse did indeed have a daughter named Janet, who died in a motorcycle accident in 1976 at the age of twenty-two. Playfair’s book discusses this detail, and reports that a Dutch medium named Dono Gmelig-Meyling, who visited the house towards the end of the ordeal, identified the spirit of Janet Grosse as the cause of the disturbances. The Enfield Haunting uses Grosse’s bereavement as his central character motivation: Grosse’s first scene in each of the three episodes is either a nightmare or a flashback confronting him with his daughter’s death. In The Exorcist, the younger priest is preoccupied with a deceased mother; in The Enfield Haunting, the older researcher is preoccupied with a deceased daughter.

The fictionalized Grosse comes to see Janet Hodgson as a surrogate daughter; in return, Janet — whose parents are divorced — accepts Grosse as a father figure. The main character conflicts arise from this relationship: Playfair accuses Grosse of letting his bereavement colour his research; Grosse’s wife accuses him of neglecting her in favour of the Hodgson family; and Janet’s father, who briefly turns up in the second episode, sees Grosse as a predator. After the poltergeist (conclusively identified as the ghost of former resident Joe Watson) is driven out in the final episode, Janet Hodgson becomes possessed by a number of other spirits, including that of Janet Grosse. Only once Maurice Grosse finally confronts his daughter’s presence and puts her to rest can the two families — the Hodgsons and the Grosses — be healed of their respective traumas.

The relationship between Janet Hodgson and Maurice Grosse as depicted in the series is contrary to Playfair’s version of events, as he reports in his book that “Janet regarded us as part of the furniture rather than as father-substitutes”. However, it is entirely consistent with the subtext of The Exorcist: Regan had an absent father, and was implicitly replacing him first with the spiritual entity she contacted through her Ouija board (the novel stresses the similarity between the name used by the spirit, Captain Howdy, and that of her father, Howard) and later with the priest Father Karras. The Enfield Haunting makes explicit this father/daughter relationship between researcher and poltergeist girl, which becomes the core of the series’ emotional drama. Janet would find a different surrogate father in the next major screen version of her story: The Conjuring 2, released in 2016.

Thrills and Spills: The Conjuring 2

Among the many visitors to the site of the Enfield poltergeist were the American paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren. The successful 2013 film The Conjuring was based on a case investigated by the Warrens in the US; the sequel, meanwhile, follows the fictionalized versions of the Warrens to the Enfield home of Janet Hodgson and her family.

The Conjuring 2 departs even further from the facts than The Enfield Haunting. The incident with the Ouija board, mentioned as a minor detail in Playfair’s book, is used as the trigger for the haunting — suggesting that the film’s story is modeled partly upon that of The Exorcist. Another plot element, a haunted music box that recites the nursery rhyme of the Crooked Man, is derived not from the Enfield case but from the original Conjuring, which likewise used a creepy music box as a prop. The film conflates the cartoonish, Tim Burton-esque figure of the Crooked Man with the elderly male apparition seen by Janet, leaving room for a spin-off film starring the character. Fidelity to the facts of the case is less important to the film than making a crowd-pleaser, one that pays homage to past horror films while paving the way for future additions to the Conjuring franchise.

The Conjuring 2‘s usage of Ed and Lorraine Warren as the heroes of its story is another franchise-mandated liberty with the facts. Speaking in a radio interview shortly before the the film’s release, Guy Lyon Playfair described himself as having been unimpressed with Ed Warren (he reserved judgement on Lorraine, who was still alive at the time):

They did turn up once, I think, at Enfield, and all I can remember is Ed Warren telling me that he could make a lot of money for me out of it. So I thought, “well that’s all I need to know from you” and I got myself out of his way as soon as I could. […] I don’t think he went there more than once. And I did read somewhere a transcript of a lengthy interview which he’s alleged to have with one of the girls — which they couldn’t remember giving him — and it was describing all sorts of marvellous wonders which I don’t think ever happened.

Playfair himself is not depicted in the film, while Maurice Grosse is present but sidelined. The loss of his daughter — so crucial to The Enfield Haunting — is mentioned in only one scene, and Grosse himself is dropped from the narrative shortly before the climax. With Grosse’s role reduced, it is Ed Warren who acts as the surrogate father figure: not only does he reassure the frightened children, he plays Elvis Presley records for them (we learn that their father did the same before the divorce) and even fixes a leak in the basement to further establish himself as man-of-the-house. The capable Ed Warren with his all-American can-do attitude is certainly a long way from The Enfield Haunting‘s flustered, uncertain Maurice Grosse.

The Conjuring 2 reaches a high-stakes climax with absolutely no basis in reality. The Warrens, having left the case alongside Grosse, make a last-minute return to the house; they arrive just in time for Ed to save a possessed Janet from stepping out of her bedroom window and being impaled on a sharpened tree stump. Meanwhile, Lorraine realises that the ghost of the old man — here named Bill Wilkins — is just a pawn controlled by the demon Valak, who manifests as a ghoulish nun (Lorraine describes it as “something that’s taken a blasphemous form to attack my faith”). Fulfilling a similar role to the Beast in Poltergeist, Valak also turns out to have been responsible for the famous haunting at Amityville in New York — which is depicted in the film’s prologue — along with a possession case integral to the backstory of the original Conjuring. All of this flies in the face of the real-life Maurice Grosse’s insistence that the Enfield poltergeist was mischievous rather than demonic; but if the Warrens are to be depicted as ghost-hunting superheroes, it is perhaps necessary for them to be provided with an equivalent supervillain. Indeed, the demonic nun was popular enough to star in her own spin-off, The Nun (2018), which owed nothing to the Enfield case and everything to Hollywood franchise-building.

Enfield of Dreams: A Summary

The identity of the ghost is as inconsistent across the Enfield fictionalizations as it is in the real-life case. Ghostwatch has a cross-dressing child predator; The Enfield Haunting has a troubled elderly man; and The Conjuring 2 has a demonic nun. Similarly, the process of dealing with the spirit varies. The Conjuring 2, like The Exorcist, shows evil being battled through Christian faith: Mrs. Hodgson tries to keep the spirit at bay by decking the walls of Janet’s bedroom with crucifixes donated by friends, and at one point the spirit turns a cross upside-down. The Warrens are depicted as devout Catholics who get involved after a local priest alerts the Church and are tasked initially with finding enough evidence to impress ecclesiastical authorities (Maurice Grosse’s Jewish background, made clear in The Enfield Haunting, is unmentioned in The Conjuring 2). Ed reassures Janet that God will “kick the butt” of supernatural evils; the girl – who, like the rest of the family, has shown no particular religious devotion beforehand – takes comfort in this notion. Ed is able to ward off the ghost of Bill Wilkins by brandishing a crucifix after the spirit admits to being “not a heaven man”. Finally, Lorraine defeats the demon Valak with an impromptu exorcism, after which Ed gives his childhood crucifix to Janet. Crucifixes feature prominently in the film’s marketing: posters showed Ed’s cross dangling in the foreground, while the DVD cover depicts a frightened Janet surrounded by inverted crosses.

This is all true to genre convention but entirely contrary to Guy Lyon Playfair’s philosophy. In his book he mentions being “very reluctant to get involved with exorcism”, particularly after learning about the death of Anneliese Michel. While he did ask Mrs Hodgson if she would like an exorcist to visit the house, she declined: “I don’t think I would be able to sleep, even if it did go away, without fearing it would come back. No, I want to get to the bottom of this myself.” Professor Hans Bender, another researcher who spoke with Playfair, concurred: “The Catholic rituale is disastrous because it is a mechanical form of applying a rite without the slightest understanding of the psychological background. You create demons, you know, by forcing them to say their names.” The 2011 edition of Playfair’s book includes an appendix entitled “What to Do with Your Poltergeist”, where the author again advises against exorcism and recommends instead hiring a psychiatrist.

The Enfield Haunting, unlike The Conjuring 2, captures Playfair’s scepticism regarding exorcism. It depicts him making a ritualised attempt to drive the spirit away after specifically stating that this is a “disobsession”, not an exorcism. The ritual itself is theistic, but hardly orthodox: Playfair is shown calling upon the “sacred principle of the universe” to grant him power over malevolent spirits, before assuring the ghost that there is no Hell and that “God forgives all” in the afterlife. On a similar note, a minor character in Ghostwatch is a self-identified Spiritualist named Arthur Lacey; after being introduced as having tried to exorcise the haunted house, he clarifies that “it wasn’t the Rituale Romanum — bell, book and candle — I simply went and prayed with the family and offered a guiding light to whatever poor soul might need it.”

All of this inconsistency makes it clear that the meta-narrative running through the three works — Ghostwatch, The Enfield Haunting and The Conjuring 2 — is not one of the ghost or the means of confronting it, but one of the girl at the centre of the phenomena: Janet Hodgson.

As a character, the fictionalized Janet lacks the porcelain-doll innocence utilised in Poltergeist and to a lesser extent The Exorcist; this is particularly true of her portrayal in The Enfield Haunting. Informed by the tradition of British “kitchen sink” drama, the miniseries shows the Hodgson girls casually swearing, trading macabre stories, and waking up to nightie-staining periods. Ghostwatch and The Conjuring 2 are not quite as committed to this approach, but there is one key character trait shared by all three of the fictionalized Janets: a capacity for tricks.

This element is derived from the real-life events, in which Janet was caught faking supernatural phenomena — something that Playfair admits in This House is Haunted. In a 1980 news broadcast (quoted in the 2011 edition of Playfair’s book) Janet was asked by a presenter if she had ever played tricks, and replied “oh yeah, a couple of times, but nothing really serious”. Playfair himself describes being on the receiving end of a prank:

I then went up to fetch my recorder and found it was not where I had left it. It took me about half a minute to find it, inside the nearest cupboard. I played the tape back, heard unmistakable sounds of Janet picking the machine up and hiding it, then went downstairs with the recorder. […] Grosse gave her a very good talking-to, after which she spent a good hour in the bathroom having a sulk.

Playfair argues that this easily-detected trick made the genuine phenomena all the more convincing. Fellow investigator Anita Gregory, however, was not convinced. In her article “Enfield on Trial” for issue 123 of The Unexplained magazine (published in 1983) she discusses an incident in which the researchers decided to secretly record Janet in her bedroom using a video camera, only for the girl to find the hidden equipment. Playfair mentions this in his book but, as Gregory points out, he neglects to mention a key detail: before finding the hidden camera, Janet was caught on video bending a spoon and bouncing on her bed.

The three major fictionalizations of the Enfield case do not avoid the element of trickery on Janet’s part, as might have been expected. Instead, they use it to generate character-based drama.

At a key moment in Ghostwatch, a mysterious knocking turns out to be the Janet Hodgson stand-in character Suzanne banging a toy telephone against the wall; caught in the act, she pleads through tears that she merely wanted the investigators to stay. Given that the drama’s pseudo-documentary format inevitably turns much of the cast into props rather than characters, this moment is the only point in the narrative where Suzanne shows any personal agency. Similarly, The Enfield Haunting has Janet faking ghostly phenomena in a misguided attempt to bond with the investigators: one scene depicts a fictitious event where a tear-soaked Janet telephones Maurice Grosse’s wife, purporting to be the ghost of the Grosses’ daughter. The issue of Janet’s trickery has a more sinister angle in The Conjuring 2, where she fakes poltergeist phenomena on camera after the demon threatens to harm her family unless she drives the investigators away.

Whatever her motives, the fictional Janet shows a degree of personal agency that gives insight into her character — and, in the process, separates her from prior poltergeist girls.

The Exorcist’s Regan MacNeil was less a character, more an iconic depiction of an idealised childhood; she developed a new dimension only when the demonic personality took over her body. Carrie White, tossed back and forth between her oppressive mother, her bullying school environment and her confusing psychic powers, showed little personal agency until her final destructive turn. Carol Anne Freeling from Poltergeist returned to the Regan model of poltergeist girl as innocent, this time not only idealised but also infantilised. Emily Rose — that cinematic ghost of Anneliese Michel – was dead before the film’s story started, appearing in flashbacks as either helplessly deluded or a puppet of demonic forces, depending on interpretation.

But with the character of Janet Hodgson appearing across the multiple Enfield dramatisations, we see a poltergeist girl of a different sort. Janet’s mind is sometimes taken over by the spirit, but only temporarily. When she is conscious she is allowed space for her own personality. She is emotionally unstable, and at certain points, she is prone to misleading the adults through faked poltergeist phenomena. She is intellectually curious and open to whatever spiritual explanations and solutions the researchers offer her. She shows personal anxieties, nuanced relationships with friends and family, a yearning for a father figure, hopes for the future, and even a fondness for Elvis records.

In short, it is with the fictionalized Janet Hodgson that we finally meet the girl behind the poltergeist.