Underneath the butt jokes and ‘80s flashbacks (and more butt jokes), Teen Titans Go! To the Movies poses a valid and complex question: Why don’t we have a Robin movie? Robin (the Dick Grayson iteration) was introduced before Wonder Woman, Captain America, and a host of other superheroes who have been given their own films. The character has not been out of print since his initial introduction, a clear indication of his popularity. Although Robin has appeared in films alongside Batman and in this most recent movie with his Teen Titans team, he has yet to star in his own film. What gives?

Although in Teen Titans Go! To the Movies, the team hypothesizes that Robin can’t star in his own movie without an arch-nemesis, the primary answer lies in the doubly subordinate role of the teen sidekick. Sidekicks are by definition not the stars of their stories, and, as it turns out, teenagers as we know them weren’t the stars of any stories until around the mid-century.

The Invention of Teenagers

The concept of the “teenager” is not old—in fact, the word wasn’t even used in print until 1941. Robin’s introduction in 1940 thus reflects the crystallization of myriad social, political, and economic factors into the image of the American adolescent. These factors primarily stemmed from a crisis in the meaning of masculinity around the turn of the twentieth century.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the United States diversified and the so-called “frontier” closed. In turn, the very foundations of American of masculinity (namely, bootstrap imperialism) were called into question and redefined (think of Teddy Roosevelt and his near hysterical big-sticking). This confusion about the meaning of manhood also implied confusion over the meaning of adulthood. Even a brief review of history reveals that (white) male bodies have almost always been the only ones with any real access to adulthood and its attendant privileges (voting, land ownership, etc.).

How were these twin crises of maturity and masculinity solved? Enter adolescence.

Often described as being “discovered” around the turn of the twentieth century, adolescence was most notably described in 1904 by G. Stanley Hall. Hall and others addressed fears of masculinity and maturity in their “discovery” of adolescence—now that they supposedly knew better what adolescents were like and what they needed, the youths could be carefully supervised and groomed for mature adult life.

(“Of course! It’s not like masculinity and maturity are themselves constructs wobbling atop constantly shifting definitions, amirite? Masculinity and maturity were only in crisis because we didn’t understand before how to properly prepare young people for adulthood! You’re all welcome.”–G. Stanley Hall, probably.)

Over the next few decades, more and more attention, time, and care was poured into supervising and monitoring adolescents, especially boys. Hall and his cohort weren’t discovering adolescence so much as creating it, and it came to be viewed as a contrast which helped clarify maturity by demarcating what maturity is not. Unlike childhood, which was closely tied to femininity and motherhood, adolescence was imbued from the beginning with connotations of masculinity and represented the path to maturity—assuming the adolescent in question had the proper guidance from adults.

Any failure of an individual to reach “proper” adulthood was attributed to underdevelopment or improper preparation during adolescence. In this way, adolescence became the time and space in which many cultural anxieties (about masculinity, sexuality, and even race) were meant to be ironed out by informed, watchful adults.

The creation and popularization of comic books neatly parallels this increased interest in adolescence. Comic books were one of the first forms of media designed for and marketed to children and adolescents. Sure, there had been books for children and radio programs for youth prior to the late 1930s, but these were niche iterations of popular media forms initially created with adults in mind. Comic books, on the other hand, were originally for kids, and they both reflected the increased interest in youth and helped promote it by turning youth into its own sub-market.

While other genres of comics existed prior to superhero stories, none captured the attention of young people quite like caped crusaders. The superhero genre was born in 1938 with the introduction of Superman in Action Comics #1; Batman followed closely in 1939’s Detective Comics #27. A mere eleven issues later, Batman’s young sidekick, Robin, was introduced.

The Indispensable Teen Sidekick

In Teen Titans Go! To the Movies, there is a scene in which the team attends the latest superhero movie and are treated to some trailers. At first Robin believes the new movie about “Batman’s closest ally” is about him, but it turns out to be a movie about Bruce Wayne’s butler, Alfred.

Further humiliation ensues when trailers for a Batmobile movie and a Bat-utility belt movie follow. Interestingly enough, Robin’s function in Batman stories is much more akin to the utility belt than anything else—both exist as repositories and tools adorning Batman to make his heroic work possible.

Created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger, Robin’s introduction was meant to humanize Batman and provide access to the inner workings of the genius detective’s mind and methods. However, Robin has also always performed important cultural work in providing a contrast to Batman.

As an adolescent, Robin’s existence serves to deflect and distract from questions about Batman’s own status, just as real-life teenagers provide theoretical safe harbor for uncertainties about masculinity and maturity. The emphasis on Robin’s adolescence, signified by his impulsiveness and reckless risk-taking, makes Batman appear capable, knowing, and professional in comparison. Robin’s distractingly bright costume and demeanor cast Batman’s relative reserve into high relief.

In short, Robin normalizes Batman’s otherwise odd enterprise. What’s weirder than a non-superpowered 30-year-old guy in a black cape fighting crime at night? You guessed it—a 13-year-old kid in a yellow cape and green hot pants fighting crime at night. Robin thus reveals the facility of the teenager in shoring up notions of adult masculinity.

Though Batman and Robin’s relationship hasn’t always worked out the way it’s supposed to (see the 1960s television show, when both characters appeared decidedly ridiculous), the general function of adolescent sidekicks has held through multiple Robins, Speedys, and Kid Flashes over the decades. Each of these teen characters gives their heroic partner (always a straight white adult male, despite occasional changes to the social identities of sidekicks) a point of contrast and means of demarcating their own maturity.

Early comics featuring Batman and Robin emphasize Robin’s own innocence, recklessness, and small stature, indirectly making Batman himself appear more knowledgeable, capable, and imposing. Robin was frequently captured and in need of rescue by Batman in these early comics (as well as episodes of Super Friends in the 1970s and both Batman: The Animated Series and Joel Schumacher’s film Batman and Robin in the 1990s), offering opportunities to emphasize Batman’s maturity and strength compared to Robin’s youth and weakness.

The duo would work as a team in comics until 1969, when Robin left for college in Batman #217. This moment itself is instructive as to how inseparable the Dynamic Duo had become: as Robin’s car disappears over the horizon, Batman tells a saddened Alfred that they will move on “[by] becoming new—streamlining the operation! By discarding the paraphernalia of the past … By re-establishing this trademark of the ‘old’ Batman” (Robbins and Giordano, Batman #217).

So is this the new Batman, or a return to the old? Even Batman himself, and by extension the author of the comic, seems confused as to whether Batman has ever existed without Robin—and as to whether Robin is a person or “paraphernalia,” something like a car or a utility belt.

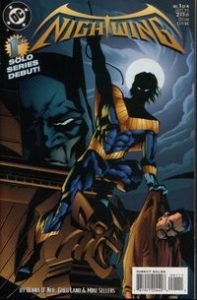

After Sidekicking—Or, Why Nightwing Can Have a Movie but Robin Can’t

Just as a movie about the Batmobile would be difficult to sell (though maybe awesome?), so would a movie about a sidekick who is alone. Examining the historical record, as it were, it appears sidekicks can have “careers” once they split from their partners in just two ways: by joining a team or changing their identity.

Teen Titans Go! To the Movies is an example of the former. Although the film is nominally about Robin’s quest to get a movie made about himself (as with most iterations of “Go!,” the plot takes a backseat to pretty much everything else), he is in fact one of the stars of this film. He is accompanied by Raven, Starfire, Cyborg, and Beast Boy, a team with which the Boy Wonder has had considerable popularity.

After Batman #217, creators struggled to craft a solo identity for Robin. By emphasizing the dark and angry roots of Batman’s backstory, authors successfully wrote Batman solo (for a while, at least—a new Robin was introduced in 1983 and several more have followed since), but Robin had little emotional depth to mine. He was, after all, merely a foil, a demarcation, a black mirror for Batman. What happens to a reflection when the subject steps away?

In the 1980s, writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Perez discovered one of the keys to post-sidekick sales by rebooting a team of sidekicks called the Teen Titans. Originally comprised entirely of former sidekicks, Wolfman’s version kept sidekicks Robin, Kid Flash, and Wonder Girl, and added non-sidekicks Starfire, Raven, Cyborg, and Beast Boy to the team. He called them the New Teen Titans.

The New Teen Titans stories focused on adolescent drama and soap-opera style narratives. The sidekicks did not function as sidekicks, per se, but neither did they star in their own stories. Instead, arcs were buoyed by interpersonal (and often romantic) conflict and resolution. Rather than telling superhero stories without the heroes, Wolfman took teen sidekicks and told stories about the teens.

In this sense, teamwork for former sidekicks allows them to continue doing what it is they were designed to do: interact with other characters in a way that is far more personal than professional. Instead of shoring up the maturity of their heroic partner, the Teen Titans emphasize the adolescence of each other.

Strangely, the newest iteration of this Titans team seems poised to ignore much of what has made them successful in the past. The CW Seed’s show Titans will be available to stream beginning this fall, but the first trailer for the program hints at little of the interpersonal drama that drove previous iterations of the team (including GO!, in its own weird way). The trailer offers no glimpses of Robin and Starfire’s will-they-won’t-they relationship or Beast Boy and Cyborg’s eternal bromance.

The trailer does show Robin sporting a shirt and tie in an interrogation room, indicating this is an older Dick Grayson already employed in his adult alter ego as a detective in a police department. He also expresses some ~choice words~ regarding Batman, and yet still wears a Robin costume. It seems the show will be mobilizing both historically profitable trajectories for former sidekicks—teamwork and dramatic changes in identity.

This latter path to a successful post-sidekick career is rather elegant in its simplicity: become the hero. Yet again, Robin provides one of the earliest and best examples of this sort of transition in his taking on the mantle of Nightwing.

Although three different versions of this origin story appear in comics, the commonalities are that Robin is a few years older, has been working with the Teen Titans for some time, and being a sidekick is just not enough for him anymore. Becoming Nightwing symbolized Robin’s growth from “just a sidekick” to something more substantial: a superhero with his own skills and methods, and eventually his own setting, villains, and alter-ego as a cop and then detective.

It took about ten real-time years after Robin first donned a Nightwing costume for him to star in his own comic mini-series, penned by Dennis O’Neill. Nightwing has had a solo title for nearly all of the twenty-three years since. Robin (though not the Dick Grayson version or the second Robin, Jason Todd) wouldn’t get his own title until Tim Drake’s eponymous 1991 series—51 years after his introduction.

As of 2018, a Nightwing movie is in the works, though it looks as though production may be years away. After over seventy years, Dick Grayson is getting a solo film, but not as Robin.

Robin (as Robin and Robin alone) will never have his own movie: the construction of the teen sidekick is such that their role is purely relational. The core of Robin’s identity is in his interactions with others as a supportive partner or team leader, but rarely if ever in a starring role—and certainly not in his own Hollywood blockbuster.