Women Write About Comics celebrates the 150th anniversary of J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla with a series of posts on female vampires in nineteenth-century literature.

While vampire fiction may have a reputation as being somewhat trashy and lowbrow, the fact is that major canonical writers of several countries had parts to play in developing the form. In Britain, it was Lord Byron; in France, Alexandre Dumas; and, heading further east, we meet Nikolai Gogol, a Russian-Ukrainian author known for his combination of human insight and grotesque nightmare-imagery.

Gogol used vampire-adjacent elements in his 1832 tale of an evil sorcerer, “Strashnaya mest” (translated into English by Constance Garnett as “A Terrible Vengeance”). This story posits that sinners are punished after death by having the corpses of their victims feed upon their bodies:

The sorcerer died instantly and he opened his eyes after his death: but he was dead and looked out of dead eyes. Neither the living nor the risen from the dead have such a terrible look in their eyes. He rolled his dead eyes from side to side and saw dead men rising up from Kiev, from Galicia and the Carpathian Mountains, exactly like him.

Pale, very pale, one taller than another, one bonier than another, they thronged around the horseman who held this awful prey in his hand. The horseman laughed once more and dropped the sorcerer down a precipice. And all the corpses leaped into the precipice and fastened their teeth in the dead man’s flesh. […] And often in the Carpathians a sound is heard as though a thousand mills were churning up the water with their wheels: it is the sound of the dead men gnawing a corpse in the endless abyss which no living man has seen for none dares to approach it.

Gogol tackled the vampire theme more directly in his 1835 tale “Viy”; this title is typically rendered as “The Viy” in the English-speaking world, with Claud Field’s translation having appeared in the 1915 collection The Mantle, and Other Stories. The story takes its name from a grotesque troll-like being – the Russian Wikipedia indicates that there is some scholarly dispute as to how much this Viy comes from folklore and how much is Gogol’s invention. However, the Viy appears only at the very end of the story; until then, the principal supernatural character is a witch with vampiric tendencies.

The story opens in bustling Kyiv, where Gogol paints a sardonic picture of the local academic community as a group of students make their way through the city, showing their various rivalries and idiosyncrasies. One of the students, trainee philosopher Khoma Brutus (whose name was anglicised as Thomas in the translation), takes a long trip outside the city with two companions. Night falls sooner than they expected, and they are forced to stop off at a small village.

There, they meet a housekeeper who is initially unwelcoming. “I know these philosophers and theologians”, she declares; “when once one takes them in, they eat one out of house and home. Go farther on! There is no room here for you!” However, they are able to persuade her to provide board: “The old woman found a special resting place for each student; the rhetorician she put in a shed, the theologian in an empty store-room, and the philosopher in a sheep’s stall.” Then an incident occurs when Thomas, the philosopher, is startled by the old woman’s manner:

He jumped up in order to rush out, but she placed herself before the door, fixed her glowing eyes upon him, and again approached him. The philosopher tried to push her away with his hands, but to his astonishment he found that he could neither lift his hands nor move his legs, nor utter an audible word. He only heard his heart beating, and saw the old woman approach him, place his hands crosswise on his breast, and bend his head down. Then with the agility of a cat she sprang on his shoulders, struck him on the side with a broom, and he began to run like a race-horse, carrying her on his shoulders.

As an aside, it is interesting to note that Thomas is suffering a nightmarish situation while being literally ridden by a hag, considering the English term “hagridden” and its association with nightmares and sleep paralysis: Gogol appears to be drawing from a deep and widespread body of folklore. The dreamlike sequence continues with Thomas speeding through the night and into a dark wood, still carrying the old woman piggyback-fashion and having apparently lost control over his body, dashing into a realm of weird magic:

A strange, oppressive, and yet sweet sensation took possession of his heart. He looked down and saw how the grass beneath his feet seemed to be quite deep and far away; over it there flowed a flood of crystal-clear water, and the grassy plain looked like the bottom of a transparent sea. He saw his own image, and that of the old woman whom he carried on his back, clearly reflected in it. Then he beheld how, instead of the moon, a strange sun shone there; he heard the deep tones of bells, and saw them swinging. He saw a water-nixie rise from a bed of tall reeds; she turned to him, and her face was clearly visible, and she sang a song which penetrated his soul; then she approached him and nearly reached the surface of the water, on which she burst into laughter and again disappeared.

In the midst of his ordeal, Thomas is still able to “repeat all the prayers which he knew, and all the formulas of exorcism against evil spirits.” After this, he manages to wrench himself out from under the witch and clamber onto her back, hitting her with a stick as she carries him along the route back to Kyiv. Finally, the witch collapses from the strain. When Thomas sees her lying on the ground, he finds that she has transformed: no longer an elderly woman, she has taken on the appearance of a beautiful, long-eyelashed maiden.

Back in Kyiv the next day, Thomas learns that a young woman – the daughter of a rich colonel – is on her deathbed after a long and arduous walk, and desires for prayers to be spoken over the course of three nights after her passing. Curiously, she wishes for one man in particular to recite these prayers: Thomas Brutus.

Yet Thomas insists that he has no idea who she is. The idea fills him with foreboding, although he is unable to explain why. The girl duly expires and Thomas finally decides to fulfill her last request, spurred on partly by the idea of payment from her wealthy father. When he sees her body, however, Thomas makes a terrible discovery: the dead girl is the witch he had encountered the previous night – still in the form of the beautiful maiden.

Despite foraying into otherworldly horror, the story keeps its strain of satirical humour. In one scene Thomas overhears a group of men taking part in a superstitious conversation about how to identify witches, with one maintaining that every witch has a tail. The talk then turns to a certain local named Mikita, and Thomas is intrigued enough to ask for more information, prompting the others to stumble over each other for the honour of narrating Mikita’s story.

The tale turns out to be more absurd than scary, and deals with Mikita meeting a strange fate after seeing a mysterious young woman: first, he began trotting around like a horse; this wore him out so much that he dried up and finally crumbled into ashes. The men then tell a different narrative, one focusing on a woman named Cheptchicha and her baby, and this is where vampirism enters Gogol’s story:

“…So she seized the poker and opened the door. But hardly had she done so than the dog rushed between her legs straight to the cradle. Then Cheptchicha saw that it was not a dog but the young lady; and if it had only been the young lady as she knew her it wouldn’t have mattered, but she looked quite blue, and her eyes sparkled like fiery coals. She seized the child, bit its throat, and began to suck its blood. Cheptchicha shrieked, ‘Ah! my darling child!’ and rushed out of the room. Then she saw that the house-door was shut and rushed up to the attic and sat there, the stupid woman, trembling all over. Then the young lady came after her and bit her too, poor fool! The next morning Cheptoun carried his wife, all bitten and wounded, down from the attic, and the next day she died…”

The two tales apparently deal with the same young witch, and others present have still more stories to tell of her – stories in which she steals caps and pipes, cuts off girls’ plaits, and drinks blood by the pint. And this is the woman who =]]Thomas has agreed to recite prayers for, every night for three nights!

Despite his anxiety, he turns up at the church where the witch’s body is held – only for his every fear to be confirmed when she rises from the dead:

Yes, she was no longer lying in the coffin, but sitting upright. He turned away his eyes, but at once looked again, terrified, at the coffin. She stood up; then she walked with closed eyes through the church, stretching out her arms as though she wanted to seize someone. She now came straight towards him.

As with his first encounter with the witch, Thomas utters prayers and formulas for exorcism, this time drawing a protective circle around himself to block off the revenant’s advances:

She had almost reached the edge of the circle which he had traced; but it was evident that she had not the power to enter it. Her face wore a bluish tint like that of one who has been several days dead.

Thomas had not the courage to look at her, so terrible was her appearance; her teeth chattered and she opened her dead eyes, but as in her rage she saw nothing, she turned in another direction and felt with outstretched arms among the pillars and corners of the church in the hope of seizing him.

Thwarted, the witch returns to her coffin – at which point the coffin itself rises, whizzing around the church, but still unable to breach Thomas’ circle. Then comes cock-crow and the phenomena cease: Thomas has completed his first night of prayers.

But two nights remain. The second night comes and the witch rises once more, again confronting Thomas with chattering teeth and outstretched arms, uttering “words that sounded like the bubbling of boiling pitch” in an effort to counter his exorcisms. The witch’s incantations are followed by poltergeist-like phenomena: a stormy wind within the church, the sound of birds clawing and flapping against the building’s windows, and heavy blows on the church door.

Once again Thomas succeeds in reciting all of the necessary prayers until cock-crow, but the strain is heavy. The next morning, he imbibes a whole quart of brandy after being helped out of the church, and looks in a mirror to find that his hair has turned grey.

This ordeal leaves Thomas reluctant to finish his job. Even after the colonel threatens him with violence unless he comes back for the third and final night for one more round of prayers, he still tries to evade his duty. Despite his efforts, he is forced to return to the church and confront the living corpse of the witch:

Suddenly in the midst of the sepulchral silence the iron lid of the coffin sprang open with a jarring noise, and the dead witch stood up. She was this time still more terrible in aspect than at first. Her teeth chattered loudly and her lips, through which poured a stream of dreadful curses, moved convulsively. A whirlwind arose in the church; the icons of the saints fell on the ground, together with the broken window-panes. The door was wrenched from its hinges, and a huge mass of monstrous creatures rushed into the church, which became filled with the noise of beating wings and scratching claws.

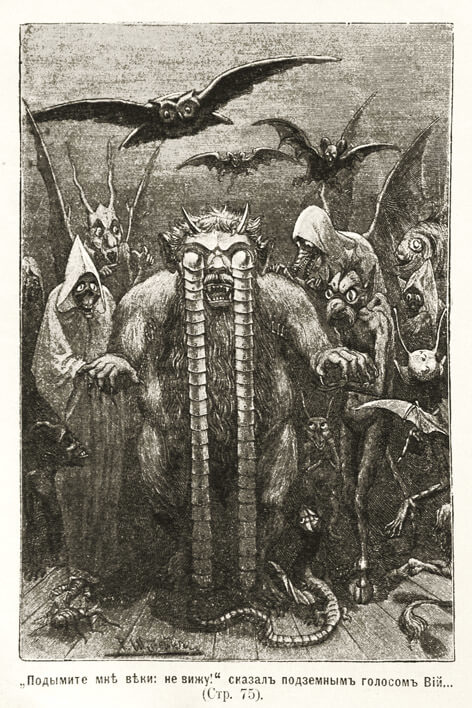

The otherworldly beings that have infiltrated the church range from a shaggy-haired, glowing-eyed beast to something “like a gigantic bladder covered with countless crabs’ claws and scorpions’ stings, and with black clods of earth hanging from it.” Then, the witch invokes the most fearsome of all these creatures – the Viy:

A sudden silence followed; the howling of wolves was heard in the distance, and soon heavy footsteps resounded through the church. Thomas looked up furtively and saw that an ungainly human figure with crooked legs was being led into the church. He was quite covered with black soil, and his hands and feet resembled knotted roots. He trod heavily and stumbled at every step. His eyelids were of enormous length. With terror, Thomas saw that his face was of iron. They led him in by the arms and placed him near Thomas’s circle. “Raise my eyelids! I can’t see anything!” said the Viy in a dull, hollow voice, and they all hastened to help in doing so.

“Don’t look!” an inner voice warned the philosopher; but he could not restrain from looking.

“There he is!” exclaimed the Viy, pointing an iron finger at him, and all the monsters rushed on him at once.

Thomas is killed and the church is abandoned by its parishioners, eventually becoming overgrown with plants. The story ends with a call-back to an earlier, more humorous sequence as the locals discuss Thomas’ fate:

“I know why he perished,” said Gorobetz; “because he was afraid. If he had not feared her, the witch could have done nothing to him. One ought to cross oneself incessantly and spit exactly on her tail, and then not the least harm can happen. I know all about it, for here, in Kieff, all the old women in the market-place are witches.”

“The Viy” has seen a number of screen adaptations, some more accurate than others. In terms of fidelity, the comparatively little-known 1996 animated short film made in Gogol’s native Ukraine is remarkably faithful in both spirit and letter. The dramatisation best-known internationally is Mario Bava’s 1960 film La maschera del demonio (released to Anglophone markets as Black Sunday); but while a classic of vampire cinema, this has almost nothing in common with its ostensible source and could just as easily have been billed as an adaptation of Dracula or Carmilla.

Gogol’s grotesquerie is a world away from the more conventionalised vampires depicted (albeit to great effect) by Bava. The undead woman in “The Viy” does not follow the same tidy set of rules as the garlic-bound Count Dracula, instead existing in a fundamentally ambiguous and liminal state.

She shapeshifts from an old hag to a young maiden. Her crimes range from trivial poltergeist-like fare – stealing hats and pipes – to horrific acts of blood-drinking. She is a denizen of the supernatural plane that she shares with all manner of weird creatures up to and including the bizarre Viy, and yet also the daughter of a wealthy colonel who appears to have not one trace of magic about him.

In other words, she is a character into whom Gogol pours all of the dreamlike weirdness that comes with the actual folklore of witches and vampires.

Next week: Another Slavic tale…