Coming of age is uncomfortable. As teens become young adults, it’s good and necessary to test boundaries, take risks and make mistakes. That’s part of how we learn about ourselves and chase down the question of identity. However, it’s often not a fun or simple process, and I love stories that reflect that reality — stories like Sophia Glock’s new memoir, Passport.

Passport is, on the surface, Glock’s memoir about learning that her parents were CIA Agents who kept their work secret from their children. However, on a deeper level it’s about how the relationships in Glock’s life shaped her as a person. Those relationships were affected by the secrecy in her family, but they were also strongly influenced by her complicated feelings toward her family members – especially the older sister she greatly admired. Glock also moved frequently, to 6 different countries total as an adolescent, and held a deep desire to forge lasting connections. Then there is, of course, her relationship to her country of origin – a place she’d never really lived, but whose culture and geopolitical power still dominated her life.

Following Glock as she finds her own identity within this complicated whirl of relationships is fascinating, tense and relatable. Friendships drift and fall apart, crushes go unrequited, and siblings and parents become fuller, more complex people as Sophia herself becomes a fuller, more complex person. I loved and appreciated seeing Glock embrace the discomfort of growing up in this memoir, and was delighted to speak with her over email about her creative process and, of course, all those relationships.

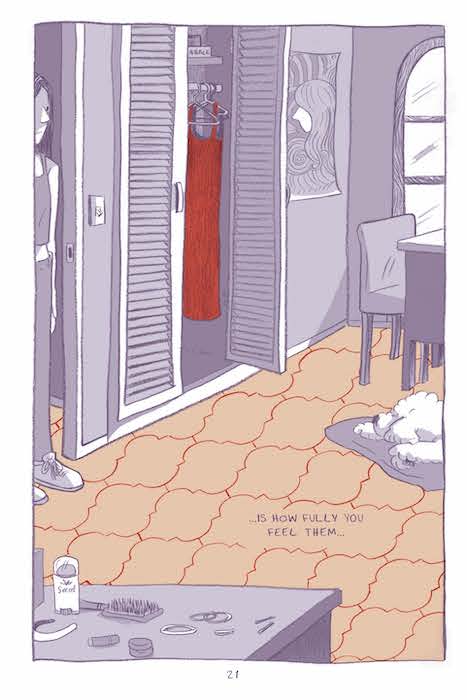

In our last interview in 2017, we talked about how you developed your drawing style – bold, clean lines and heavy shading and cross hatching that give your stories a heavy emotional weight. When I first opened Passport the art felt immediately familiar to me, but there are key differences. I think they’re encompassed well in a full page illustration early on in the comic — teen Sophia stands in her sister’s empty room, recently vacated as her sister returned to the United States for college. Most of the art in the book is gray with a mix of that denser shading as well as clean blocks of color. In this illustration, the floor is a peach color that is also prevalent in the book. Crucially, the red dress that your sister left behind is actually red —a vibrant and kind of threatening color that stands out from the rest of the color palette.

I love this illustration! We really feel the way the absence of her sister presses down on teen Sophia, but the vibrant red of the dress warns us about how the ideas taken from or projected onto herr sister about the ideal teen experience will have a strong effect. However, I also want to start here because it pulls together all the colors we see in the story, and the wide variety of textures – the patterns on the windowsill and the posters on the wall, sharp bristles on the hairbrush on the table. How did you choose the color palette for Passport, and what was your process for drawing this book? Was it very different from how you’ve made comics in the past?

I developed the book’s overall color palette by basing it on a ubiquitous color scheme throughout my childhood; that of red and blue. It reminds me of air-mail envelopes, the American and British flags, airline branding, and most uniforms I wore in the various schools I attended. When I turned down the opacity of that bright red and deep blue I ended up with these peachy pinks and light greyish blues which pleased me, so I ran with it. I kept the blue for the line work, and the bright red for some crucial visual details, like the dress. And writing the story of that dress was very fun, and yes, it is based on a real dress of my sister’s, which is probably still hanging in a closet somewhere. But like many characters in the book, it is a composite dress, meant to play the role of several sartorial choices I made in high school.

The entire book was drawn in black colored pencil, which I was hoping would capture something of my initial drawing style which I fear gets lost in the inking stage. I’m not sure if I managed to retain the feel of my pencil stage, but it did make for a softer line which tapped into the feel of my childhood a little closer than I think pen and ink would have. And I am so glad you picked up on so many details! The floors were specifically very important to me. The floors in my home were these gorgeous warm red terracotta tiles and I spent a long time recreating the exact pattern from photos.

There are a lot of interesting sensory memories depicted in Passport, like braiding hair, stuffing bags with rice and beans during Hurricane Mitch, kisses on the cheek as greeting, and even a very awkward fake kissing practice for a play. These moments made me curious about the process of remembering in order to write memoir. Are these sensory experiences ones that stick out in your memory, or were they a way of drawing out memories? Did you have diaries to work from? How did you go about reconstructing the past so you could draw it out in a story?

My process of recalling memories was mixed. Some memories are close to the surface, easily fished out, probably because I enjoy something about them, and others are less so, maybe because they complicate stories I tell about myself and the people I love. My diaries were essential to this process, because even though I pride myself on my ability to remember even minute details of my past, I am not so foolish as to believe my memory is perfect. My diaries, though obviously biased sources, helped confirm and correct, and often would trigger more memories to come to the surface. It was more work to edit my memories because my initial impulse was to include everything, but including everything makes for terrible storytelling as it turns out.

I might have a higher-than-average capacity for reliving my memories as I recall them. For example, that fake kiss? Whenever I think of it not only do I still internally cringe, but I will literally still blush. Even typing this I can feel the heat rising up my face as I re-experience the horrible sinking realization that not only was I falling in love, but that my terrible awkwardness in that moment all but guaranteed it would be unrequited. It’s terrible to know the end of the story right at the beginning. My ability to relive these moments is very useful for writing memoir, but maybe less so for not living in a state of eternal embarrassment.

Moving frequently as you did is difficult, and we see how that plays out in relationships and friendships. It’s harder to make connections and create bonds, and harder to trust the connections that you make. Over the story, it becomes clearer that the confusion and mystery surrounding your parents’ jobs and the silence that created within your family also had an impact on other relationships you made. Can you talk a bit about that impact? Were you able to create relationships that felt real and that lasted when your parents insisted each home was always temporary?

My parents’ work affected my friendships and relationships in a few ways: moving as we did, like you point out, naturally effected my ability to maintain friendships, which in turn has made me rabidly protective of the relationships I do make. There was also an idea, no doubt influenced by the nature of their work, that friends outside of the family were incidental or not to be trusted, which complicates the way my family and I deal with the world to this day even though I consciously reject that idea.

There were positive effects too. I watched my parents make friends with everyone and anyone, and I consider that a gift. My father specifically had all sort of tricks for remembering people’s names and details about their lives. I learned a lot from my parents about how to build relationships with a wide variety of people, to always be solicitous and respectful, no matter who you are talking to. My parents’ work may have furnished them with an agenda when it came to approaching the world like this, but I think it’s a beautiful way to engage with people: everyone matters, any given human you encounter has a name, a history, and potentially powerful insight into our shared world.

There is a very brief scene in which we see teen Sophia reading comics, and her (your) mother dismisses them as trash. A lot of classic, canon literature also comes up throughout the story – Jack Keroauc, Watership Down, etc. What drew you to comics in an environment that seemed to largely discourage reading them? What is the connection between books like On the Road and Dharma Bums, distinctly American novels, and this memoir, in which you reflect on being American without feeling that America is home?

My comics habit started with a fixation on the X-Men cartoon, which led to a fixation on superhero comics, which then became a debilitating and almost chemical attraction to all things comics. It was not a sanctioned literary medium in my house, but in the 90s it wasn’t broadly accepted as literature at all, so my parents were not alone in that regard. However, being well-read was valued in my family and it was also powerful cultural currency amongst a lot of the people I was trying to impress and hang out with in high school. I revered these older literary-seeming kids, and they revered the Beats and Salinger. They passed along these books as if they held all the secrets of the world; reverentially. And you’re right, I could not have chosen a more America-centric book than On The Road, but I think the Beats probably have a cross-cultural appeal to a certain type of adolescent. I did reference a lot of quintessential American books, but I also found myself including Latin American literature as I was also very influenced by that literary tradition.

Later in the comic, there is also a scene in which a student local to the area describes globalization to teen Sophia as “YOUR culture smothering everyone else’s.” Teen Sophia seems baffled by this concept – America is shown in this comic largely through classic junk food like M&Ms, or fast food from places like KFC. There is a commercial-ness to the bits of America we see, and while they have great appeal to teen Sophia, she doesn’t seem to have a strong grasp on what this means about the US government’s role in other countries. What was it like coming to terms with that concept, being the child of CIA agents?

This scene was very important to me to depict, because whereas I certainly noticed the proliferation of American corporations in many of the countries where I grew up, I took it entirely for granted why they were so ubiquitous. I never questioned the cultural dominance of American movies, music, and television until I was in high school. And then, like many things, it was a revelation to find that the world was far more complicated and nuanced than any of those movies or even your parents would have you believe. I also liked that scene because I wanted to illustrate something many international travelers experience: that of being asked to answer for or represent your country as a whole. My parents used to joke that we were “little diplomats” but that pressure to be a positive reflection of the states was real, as was others’ presumption that I could somehow speak for an entire country.

I know this is a big, semi-impossible question, but I’m curious and selfishly want to ask! I have one immigrant parent and one born-in-the-US parent but was fully born and raised here, and have my own complicated feelings about what it means to be American. How do you feel about your identity as a United States citizen today, as an adult? Has your sense of attachment or investment in that aspect of your identity changed?

It is a big question. I guess, on one hand, how I feel about my identity as an American is sort of asking me how I feel about my name being Sophia or how I feel about wearing a size 9.5 shoe. My feelings are beside the point, it’s an immutable fact, something I can’t scrub off. However, when I came back to the states to go to college I did expect to have this cozy warm feeling of “finally coming home” and that cozy warm feeling did not exactly happen. At all. I was different and I felt it. Navigating these differences was easy in the sense that they weren’t obvious. It was not a challenge in the way I imagine it is challenging to immigrate to this country. I had the right accent, the right “look”. I was not carrying around obvious cultural signifiers that I was not from here.

But I was a little off, I was missing too many cultural references and mores. I was intensely aware of how American in habit and dress everyone else was and how I seemed to be missing part of the code. I bizarrely felt more undercover than I was before, because it was obvious the way I was foreign while traveling abroad, but in the States my differences were invisible. I was both a product of and distinct from the communities I inhabited. It’s like being suspended in a perpetual in-between. One of the more gratifying aspects about writing about my childhood is connecting with all sorts of “third culture” kids and so I know I’m not alone in this respect.

My attachment to my Americanness used to be because it often felt like the only special and consistent thing about me. It’s been freeing to realize, as an adult, that I am not special at all, but this intense awareness of America and “Americanness” has remained with me. I am very much the thing, but I also have this point of view that no matter how long I am back for I can’t fully shake off. Sometimes I get homesick for being overseas now, but not because I am a “citizen of the world.” I think I miss being me over there. Maybe there is a part of me that is comfortable being uncomfortable. Which is good, because I can’t do much to change that either.

Pick up your own copy of Passport after it releases on November 30th!