Nothing makes me happier than a story that gets in my head, manipulates my emotions, and controls how I read. I am a fast reader, and poor pacing or lazy writing — whether in comic or prose form — cause me to speed through a book, letting my impatience get the better of me. This habit is why I love creators like Sophia Wiedeman, a cartoonist whose work ranges from re-examinations of fairy tales and myths — as she does in The Lettuce Girl, a book based on Rapunzel — to deeply personal, autobiographical comics, and meditations on familial relationships. No matter the genre, Wiedeman’s comics are always economical; every piece of dialogue, each cross hatch, and even gutter spaces lend a hand in telling the story.

When Wiedeman sent me review copies of her newest zines, Born, Not Raised and Over Ripe, I knew I had to try and coax her into telling me the secrets behind her masterful storytelling. We spoke over email about how she developed her singular style, mother/daughter relationships in her work, and food.

You have a very unique drawing style; in particular, I like how you balance smooth line work with dense line work or shading. How did you develop your style? Why do you usually work in black ink, without color?

Sophia Wiedeman: I think it’s the result of both what I liked to look at when I started drawing comics as well as my early limitations. Cartooning is the act of stripping things down to the essentials, but when I started cartooning, it was almost as if I had to forget how to draw altogether. I wanted to draw the whole world, but young cartoonists usually cannot sustain an ultra-saturated, hyper realistic, highly developed description of reality. For a long time I couldn’t understand why my training in traditional studio art was not translating into my attempts to write comics. I wanted to draw like the artists I was obsessed with as a young, X-Men loving fangirl: with clean, bold lines. But, at the same time, I had a personal predilection for cross-hatching. So I stripped out all detail to make drawing manageable, and then filled it in with the one thing that (at that point in my artistic life) gave me a feeling of pleasure and control, and it has sort of evolved from there.

Sophia Wiedeman: I think it’s the result of both what I liked to look at when I started drawing comics as well as my early limitations. Cartooning is the act of stripping things down to the essentials, but when I started cartooning, it was almost as if I had to forget how to draw altogether. I wanted to draw the whole world, but young cartoonists usually cannot sustain an ultra-saturated, hyper realistic, highly developed description of reality. For a long time I couldn’t understand why my training in traditional studio art was not translating into my attempts to write comics. I wanted to draw like the artists I was obsessed with as a young, X-Men loving fangirl: with clean, bold lines. But, at the same time, I had a personal predilection for cross-hatching. So I stripped out all detail to make drawing manageable, and then filled it in with the one thing that (at that point in my artistic life) gave me a feeling of pleasure and control, and it has sort of evolved from there.

The reason I usually work in black and white is because I don’t just self-publish most of my comics; I also make them myself in my own home. Black and white, whether you or someone else prints, is just soooo much cheaper. Most anthologies I have been a part of ask for black and white work as well because those are often financed by personal funds. Working in black and white is also more efficient, because coloring doubles my workload. But I also just prefer black and white comics; I think in black and white. That being said, I have been incorporating more color into my work and publishing on the internet eliminates the difference in cost.

The transitions between stories in Over Ripe and Born, Not Raised feel very clear, despite there being no title pages or spaces between them. You have a real knack for pacing and transitions; two aspects of storytelling that I think are particularly difficult to master. What’s your writing process like? Do you have advice for writers struggling with transitions or pacing?

Sophia Wiedeman: My writing process is hard to describe. There is a lot of free association writing, and going back and forth between drawing and words. There is also a lot of hair pulling and general despair. But once I find the hook, I’ll write it down as one succinct prose piece and then create thumbnails in a grid, which is where the visual writing, the real comics work, happens. That is, composing panels, pages, and spreads.

As for developing transitions, I often imagine I’m behind a camera panning and zooming. I do not want to take for granted that the reader will know how to get from point A to point B. On one hand, you don’t ever want to underestimate the reader’s abilities. If you spoon feed the reader you strip away the satisfaction of discovery, but in order for them to get the most out of reading the story you have to be as clear as possible. Clarity and readability are two principles I keep in mind at all times. I want any vague segues to be purposeful and rare.

In terms of advice, one can achieve rhythm by establishing a strict grid and then staying married to that grid. Even when experimenting with timing and panel size, you must stay true to the underlying grid. As for making sure the pacing of your panels enhances the story, try telling your story out loud to yourself, to try and hear those natural breaks and pauses. Then write it down as succinctly as possible. A loose rule of thumb is a paragraph is a page, a sentence is a panel (or two.) Don’t be afraid of breathing room. Sometimes a panel’s purpose is to buffer one moment to the next. What’s that they say about music? Music isn’t made of notes, it’s made out of the spaces between the notes?

And overall, be a ruthless editor. When in doubt, clip it, and go again. If you think it’s unclear, it probably is. Having a trusted reader you feel safe with is also very useful. They can point out where transitions become murky, and where the narrative gets lost. It’s hard for us to see our own work clearly when we are in it, so an outside pair of eyes can be crucial.

You draw from or use fairy tales and mythology frequently in your work; Lettuce Girl retells Rapunzel and Born Not Raised starts with a comic about Leda and the Swan, while The Deformitory includes some mythical or impossible creatures. What draws you to these kinds of stories?

Sophia Wiedeman: I love these stories. I never grew out of them. I like that they are dark, sometimes subversive, and often violent. The Deformitory owes a lot to X-Men (which clearly taps into the power of myth) and also just personal stuff I was going through. I felt like such a stunted freak in graduate school (as well as many other points in my life) and it all came out in my thesis. When it came to what to write next I was lost. So, I decided to adapt a fairytale. A ready-made plot! Easy right? Sort of. I thought that I chose Rapunzel at random. It was one of my all time favorite stories but after I chose it I realized the same themes from The Deformitory were coming up again: towers, isolation, and physical abnormalities.

Sophia Wiedeman: I love these stories. I never grew out of them. I like that they are dark, sometimes subversive, and often violent. The Deformitory owes a lot to X-Men (which clearly taps into the power of myth) and also just personal stuff I was going through. I felt like such a stunted freak in graduate school (as well as many other points in my life) and it all came out in my thesis. When it came to what to write next I was lost. So, I decided to adapt a fairytale. A ready-made plot! Easy right? Sort of. I thought that I chose Rapunzel at random. It was one of my all time favorite stories but after I chose it I realized the same themes from The Deformitory were coming up again: towers, isolation, and physical abnormalities.

I think I am attracted to myths and fairy tales because they help us work out our own inner struggles and dramas. The story of Leda is so fundamentally bizarre, and yet it is a familiar cultural touchstone. Being seduced by a swan of all things, the fact that Leda’s pregnancy manifests as two eggs with a set of twins in each? It’s revolting and confusing, much like sex, assault, and pregnancy are. Theses stories are terrible and fascinating.

Myths and folktales are weird enough and removed enough from reality for us to pour ourselves into them. People try to see themselves in all stories, but fairy tales have a unique ability to absorb us. They deal heavily in archetypes and symbols, but I think their true power is in a story structure shaped by countless retellings over countless generations. An infinitude of grandparents, parents, and children have told and retold these stories, passed them along, tweaking and adding, refining, corrupting, polluting and mutating, until they often make no sense at all, but I think we are connecting on a primal level when we hear them. I was raised by a believer in Jungian analysis, so of course I pay heed to the idea of the universal unconscious. Fairytales are a powerful way we can tap into that. By borrowing these stories and ideas, by making them our own, even by updating and parodying them, we are taking part in a tradition that is as tied to our humanity as our DNA, something both larger than any one person and intensely personal.

There are some interesting relationships in your comics, particularly mother/daughter ones. Obviously a great deal of Lettuce Girl involves power and control in parent/child relationships, but I also love the comic within Over Ripe called “Night Stand.” These relationships tend to be problematic; even “Night Stand” describes the act of consuming your (or a) mother’s chocolate and using her things as a way of being close to her, but also consuming her. Is the examination of such relationships a purposeful theme in your work?

Sophia Wiedeman: I am preoccupied with the fundamental mystery of motherhood. It’s so weird, so fraught. I guess a minor theme in this interview might be that I like commonplace things that become weirder the closer you look at them. We replace our parents on some level, both physically in the world, and genetically, but also by consciously or unconsciously replicating their values, habits, and patterns in the world (often whether we like it or not). In the process we partially eradicate them, using up their resources, their youth, money, and energy. It is no coincidence that many myths and fairytales are preoccupied with destroying children before they can overpower and succeed their parents; Cronus and Rhea, Hansel and Gretel, Snow White. I don’t mean to sound so bleak, I swear I am a sentimentalist at heart, but there is a dark side to the most loving of our personal relationships.

I love the contrast in your Etsy store between these dark, beautiful, meditative comics and the adorable greeting cards with little hot dogs and potatoes! There’s a fair amount of food in the comics themselves too, do you have a special love for food? What are your favorites?

I do love food and it’s fun to draw! I actually get annoyed when movies or books don’t address how the characters eat. It’s such an essentially consuming part of our lives. It’s not so much my own personal feelings about food [as it is] how people in general feel about food, how we use it to express love, or even power, how it both sustains and seduces. I do cook a lot and it’s as close to both therapy and magic as I get in my everyday life. I love making anything I can stir a lot, anything with sesame or cilantro, and anything that can get braised for an entire day. My favorite food, though, is toast with butter.

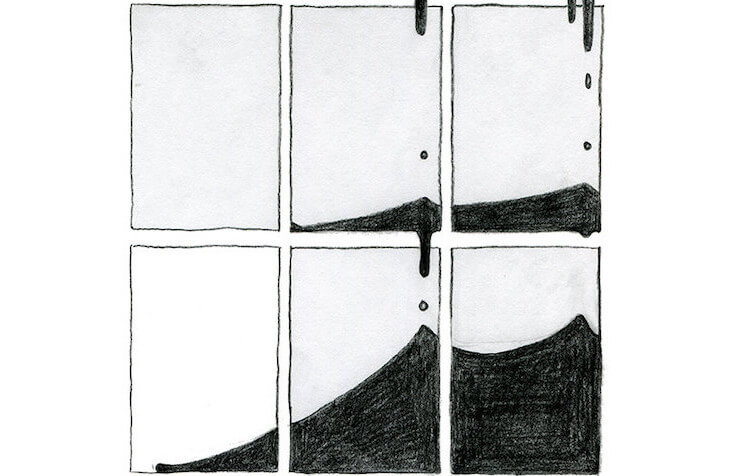

There are these circles or beans that appear in various comics and often change and evolve. Can you share insight into what they are or where they come from, or would that ruin the mystery?

Sophia Wiedeman: It’s half a mystery to me too. This is one of those visual themes that just kept cropping up. I think it stems from my fascination with the ability of something very small, a seed, a cell, a zygote, to contain within itself all the information it needs to grow into something larger. Growth itself is fascinating to me, in that it is inexorably tied to death and destruction. To grow is to transform, and in becoming new you kill the old, but the essence of that process was always locked in, from the very beginning. I don’t know where or why this began appearing in my work, but when I follow it I see it as a metaphor for human potential, and the intrinsic pain of growth.

Sophia Wiedeman: It’s half a mystery to me too. This is one of those visual themes that just kept cropping up. I think it stems from my fascination with the ability of something very small, a seed, a cell, a zygote, to contain within itself all the information it needs to grow into something larger. Growth itself is fascinating to me, in that it is inexorably tied to death and destruction. To grow is to transform, and in becoming new you kill the old, but the essence of that process was always locked in, from the very beginning. I don’t know where or why this began appearing in my work, but when I follow it I see it as a metaphor for human potential, and the intrinsic pain of growth.

Do you have upcoming projects we should be looking out for, or are you attending any cons this year where fans can catch you and buy some cute greeting cards?

Sophia Wiedeman: So far I am only planning on being at PIX in Pittsburgh on April 9th and somehow or another I always end up at SPX in Bethesda in September. Hopefully that will be the case this year too. Otherwise who knows? As for ongoing projects, I have my work cut out for me with my current one.

I usually avoid talking about works in progress, because I think talking about nascent work can sometimes kill it, but I am just tipping over into the place where it’s too real to kill. My new book is called Passport. I am showing the first completed pages at a solo show in March in Charlottesville, VA at The McGuffey Art Center (where I am an associate member.) I feel like since I completed The Lettuce Girl I have only been making short, compact pieces so I’m incredibly excited to have a long project underway again.

You can purchase Sophia’s comics and other adorable merchandise at her Etsy store or Storenvy, and keep up with her new work via her website.