It’s becoming a real Hollywood marvel.

Currently, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings—the first Hollywood superhero film with an Asian lead and full Asian cast—has grossed over $200 million domestically, making it the pandemic era’s biggest hit to date. It’s also had rave reviews from critics and fans alike, with a Rotten Tomatoes score of 92% and an audience score of 98%. On top of all this, the film has been hailed as a “massive success,” a herald of “authentic representation,” and a “watershed moment for Asian representation in Hollywood.”

But while the film generally depicted Chinese culture and identity with more care than Hollywood has seen in the past, because of its subtle lean into tired tropes it was far from perfect. The film shouldn’t be declared as the Ultimate Asian Representation. That doesn’t mean it serves no purpose though. Rather, we’re taking steps in the right direction.

Slight spoilers for Shang-Chi ahead.

As a second-generation, mixed Chinese-Canadian with a weak connection to Chinese culture, I shrugged off the Orientalist ideals that seemed trope-ish. I thought that my experience of being so used to hearing Mandarin Chinese only from villains’ mouths or seeing red and gold and traditional Chinese characters as superficial aesthetics in film was clouding my experience. However, others from the Chinese diaspora saw right through the haze.

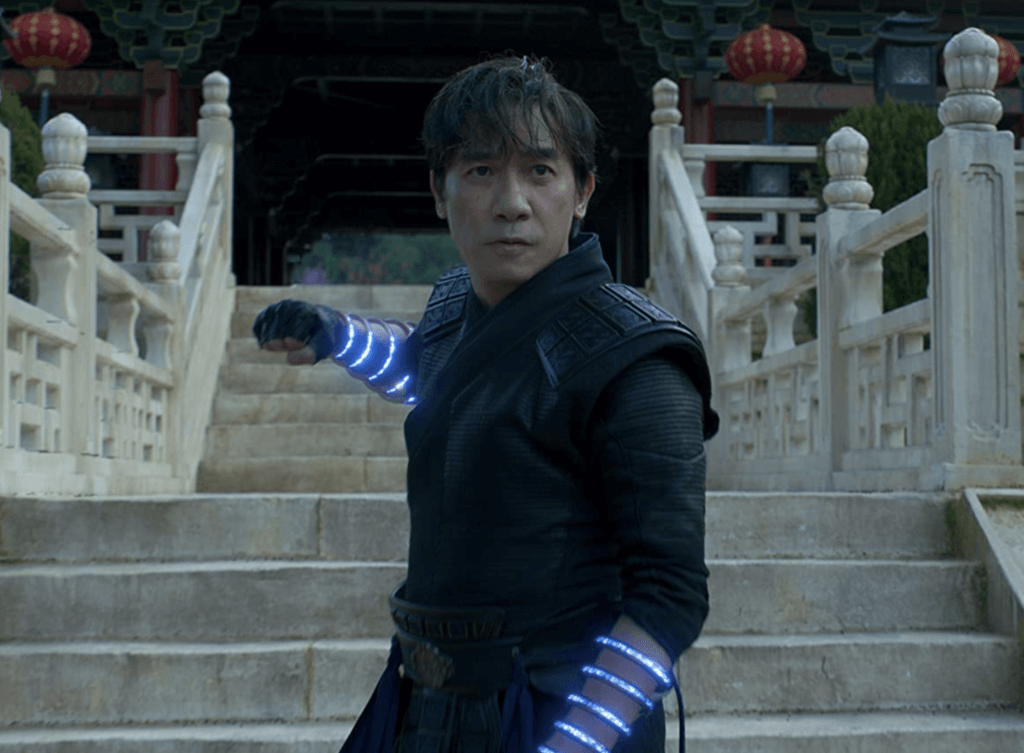

Most notably, Walter Chaw in The Washington Post called Shang-Chi an “Orientalist fantasia that presents the same old tropes in slightly updated, somewhat self-aware, very expensive packaging.” Chaw explained how the film essentially answers its lackluster attempt at addressing the conflicts within Asian-American identity with haphazard use of “exotic cliches,” unchanging views on the East, and “othering” characterization of Shang-Chi’s father, Wenwu. In essence, Chaw pointed to that subtle feeling of discomfort that I felt when watching it.

To be clear, having an Asian-American director and writer at the helm of the film did lend authenticity to its portrayal of Chinese characters and culture. A quick shot of Shang-Chi removing his shoes before entering his friend Katy’s apartment was one of these delightful touches. Still, director Dustin Daniel Cretton and writer David Callaham can only do so much when essential aspects of Shang-Chi’s story are rooted in blatant racism.

The character was inspired by the 1970s American show Kung Fu and its famed yellowface casting. David Carradine’s appeal was being a spectacle of “crazy” Chinese kung fu, as the current Shang-Chi comics writer Gene Luen Yang explained to Inverse. Editor-in-Chief at the time Roy Thomas also ordered that Shang-Chi’s father be a stereotyped villain named Fu Manchu, later claiming “it was just a joke.” While the film did take extensive measures to avoid a lot of this blatant prejudice, these components are difficult to alter in totality without changing the essence of the character’s story. The same othering, mystifying Oriental aspects unfortunately remained.

If the movie wasn’t trying to be “watershed Asian representation,” Wenwu could have just been a powerful, corrupt businessman; the climactic conflict could have been in the streets of Macau, rather than the mystical Ta Lo. But this is part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe formula: whisking the audience away to a fantastical land or idealized situation where escapism eclipses reality. It follows Disney’s tendency to use Asian cultures (Aladdin, Mulan) for fantastical aesthetics rather than meaningful storytelling that delve into the nuances of these cultures. Even the title Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings speaks to the film’s reliance on mystical, ancient aesthetics. I mean, in comparison, the third Iron Man movie wasn’t called Iron Man and the Legend of the Mandarin.

(Speaking of, the attempt at fixing Iron Man 3’s Mandarin mistakes by bringing in Trevor Slattery to play Wenwu’s court jester was just Marvel’s attempt at covering their asses. Look, we’re acknowledging that we did a bad, racist thing, please now laugh with us about it!)

What could we expect from the studio that gave us whitewashed Asian characters, white savior narratives, and infantilized Asian women? From the comic book company that has popular characters with roots in Orientalism, and that still employs an Editor-in-Chief who pretended to be an Asian man for clout? And from a parent company known for consistently misrepresenting Asian characters and appropriating Asian culture?

We truly couldn’t expect much. Still, considering all that, what we got isn’t nothing.

The very existence of a superhero film with an Asian lead and majority Asian cast can have a drastic impact, mostly by normalizing the presence and existence of Asian faces and stories to the larger hegemonic audience. When representation in media has the power to change lives, a film filled with heroic portrayals of Chinese people is bound to elicit stories of heartfelt empowerment and claims of changing tides against anti-Asian racism. (Shang-Chi certainly won’t eliminate anti-Asian racism, but for some, seeing stories they can relate to onscreen can feel like a tiny balm amidst an extra difficult year.)

We’ve lately seen this upward trend of “normalizing” marginalized identities in media. Gay coming-of-age film Love, Simon operated similarly with this intention. The movie told a story meant to educate and permeate the broader culture about gay people, rather than be a film addressed to queer viewers. This doesn’t mean that queer people can’t and haven’t enjoyed it, but it didn’t feel like media made for them as the target audience. With Shang-Chi, it’s a film that many Chinese and Asian diaspora folks are enjoying and finding themselves in, but it also feels like its main goal is ultimately to normalize Asian faces onscreen for a non-Asian audience. Yes, this can be frustrating; but when studio heads gauge a film’s viability on its widespread appeal, it’s important to acknowledge this growing pains phase.

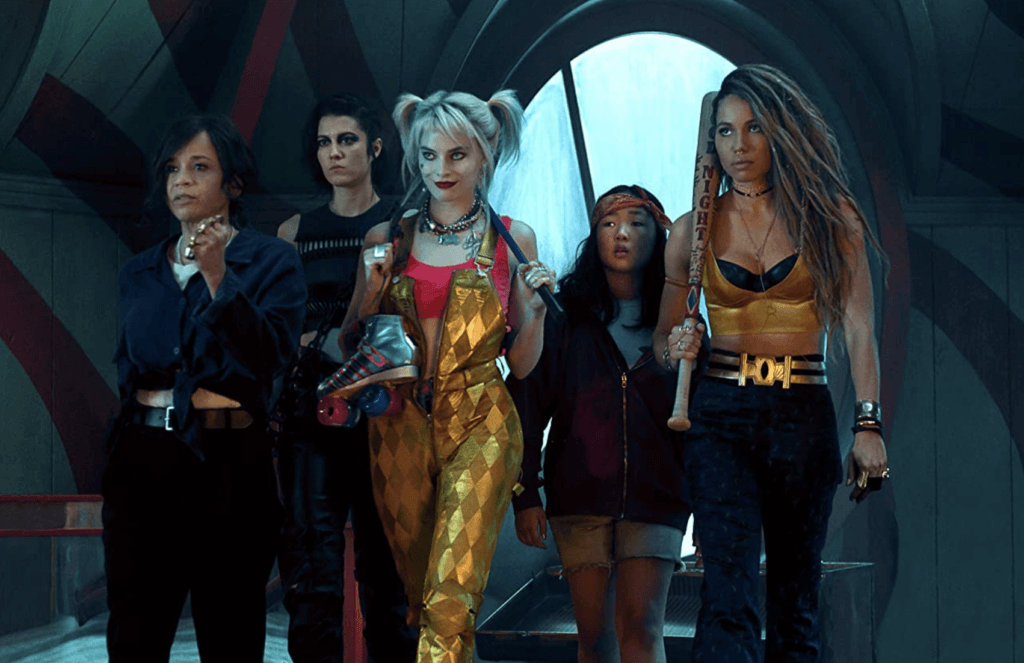

Shang-Chi is showing studio executives and those with power in Hollywood that this type of film with this type of cast can be quite profitable and sustainable. It’s like when Wonder Woman was released. Did the film have utopian female representation? Many thought it did, while many claimed it wasn’t as feminist as it made itself out to be. Regardless, the film’s monumental commercial success likely proved to studio heads that audiences would tune in for other women-led superhero movies like Captain Marvel, Birds of Prey, and Black Widow. That’s all to say that we may have to suffer a few educational Love, Simons and surface-level Wonder Womans before we see major studios green light more meaningful superhero stories made for Chinese and Asian people. (Outside of the comic book film genre, of course, there are Asian directors working hard to make nuanced films about the diaspora experience.)

The positioning of Shang-Chi as a win for the entire Asian community is part of the issue with this overzealous hype around representation. It’s quite sad that we’re relegated to championing this as a win for a myriad of disparate countries that cover half of the world when the film only really represents one (China), and a handful of them at a monogamous stretch (East Asian countries). But this just shows why this film’s aura of championing representation is needed. There hasn’t even been one lead superhero of Asian descent in an American film. Shang-Chi shouldn’t have to carry the weight of that responsibility, but for now, it has to.

I hesitate to call the film a necessary evil because beyond some critical thinking about its representation of race and the oblivious hype around it, the film is more beneficial than malicious or “hostile,” as Chaw describes. Most of the Chinese people I know adored the film and have been absorbing as much of its success as they can. My hopes for the continuing empowerment of the East Asian community that will result from this film are, if not hopelessly hopeless, still strong.

The release of Shang-Chi shouldn’t have to be a “watershed” moment. We shouldn’t have to be made to feel lucky or grateful for scraps on the table. But unfortunately, for now, this is the pace of how progressive representation is happening, at least in Hollywood. We might have to wait longer for proper, meaningful inclusion, but that doesn’t mean the wait has to be empty of any joy or wins along the way. We’re not running, but at least we’re moving.