Immanuelle Moore is a teenage girl who lives in Bethel, a town gripped by an authoritarian religion. The Good Father of Bethel’s faith is opposed by a Dark Mother, a demonic figure associated with witchcraft and devilry. Immanuelle has been treated with suspicion from birth as her late mother, Miriam, was a witch. Yet she does her best to fit into the community dominated by Grant Chambers – a man known simply as the Prophet. Indeed, Immanuelle’s close friends Ezra and Leah each have familial ties to the Prophet: Ezra is his son, while Leah is the latest young woman to join his polygamous marriage.

But one evening Immanuelle strays from the town while chasing a runaway ram. She finds herself in the surrounding Darkwood, still haunted by the ghosts of the Dark Mother’s most faithful: Lilith, Delilah, Jael and Mercy, the first four witches in history. She escapes only to return at a later date, during which she chances to have her first period – a blood offering to the witches. This is enough to awaken Lilith and her kindred, and Bethel is soon beset by a plague of blood, a plague of blight, a plague of darkness and finally a plague of slaughter.

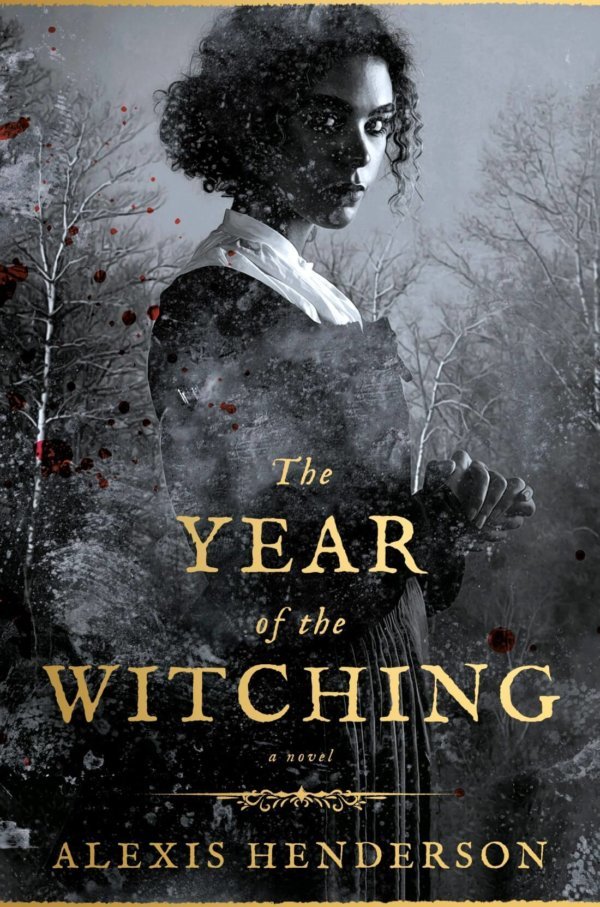

The subject of witch-hunting has long been irresistible to horror writers. Whether the hunts are taking place in Salem or in the East Anglia of Matthew Hopkins, they provide a thematic buffet: an atmospheric period backdrop; lashings of blood and brutality; a substantial body of bizarre folklore; and an opportunity to explore the politics of power and oppression. With her debut novel The Year of the Witching, Alexis Henderson offers her own take on this horror standard – a take that turns out to be both thoroughly up-to-date and just a little bit eccentric.

The Year of the Witching takes place in a setting with the general trappings of Puritan-era North America but no historical specifics. The religion of Bethel uses overtly Christian terminology – with apostles, crusaders, evangelism, and a dominant Church – and most of its adherents bear Biblical names, yet it has no direct connection to Christian theology or scripture. The characters make no reference to Jesus, for example, while their religious texts appear to consist of pseudo-Biblical snippets (“The Father loves those who serve Him faithfully. But those who stray from the path of righteousness – the heathen and the witch, the lecher and the heretic – will feel the heat of His heavenly flames”).

Similarly, there are no real-world geographical references in the novel, with the Bethelans describing the territory outside their home only as a vague land of heresy (“Gall in the barren north, Hebron in the midlands, Sine in the mountains, Judah at the cusp of the desert, Shoan south where the raging sea licked the land, and the black stain of Valta—the Dark Mother’s domain—in the far east”).

This initially raises the possibility that the walled town of Bethel is some sort of enclave that has lost touch with the rest of colonial America, but when Immanuelle begins exploring the wider landscape we find that The Year of the Witching is in fact set in a secondary world. The novel has an ambience similar to that of Christina Henry’s Alice and its sequels, which have a setting loosely resembling Victorian London and yet cut off from the history and geography of reality.

Pitting a benevolent Father against an evil Mother, the entire religion of Bethel appears to be based primarily around the oppression of women. As part of a traditional marriage ceremony, the patriarchal prophet carves symbols into the forehead of his latest bride. Immanuelle’s mother, the witch Miriam, had been a bride of the Prophet who rebelled against her husband. Meanwhile, the central moment in the joint history of both Bethel and its religion involves the first Prophet banding together an army of crusaders to massacre the four witches and their female followers, an incident that is commemorated with the witches being burnt in effigy.

It has long been common practice to view the witch-hunts through a feminist lens, of course. The Year of the Witching, a thoroughly up-to-date treatment of the stakes-and-stocks era, uses a specifically intersectional lens. While most of Bethel is white, Immanuelle belongs to a racial minority:

As for the girls like Immanuelle—the ones from the Outskirts, with dark skin and raven-black curls, cheekbones as keen as cut stone—well, the Scriptures never mentioned them at all. There were no statues or paintings rendered in their likeness, no poems or stories penned in their honor. They went unmentioned, unseen.

The dark skin of the Outskirters is associated by the Bethelans with evil, as the Dark Mother is depicted as having a swarthy complexion. We are told that some even believe the Outskirters were cursed with their skin colours as punishment (recalling the Biblical Curse of Ham and its usage to justify racism over the centuries). As well as providing racial diversity, the Outskirts turn out to be more open-minded in terms of homosexuality: Immanuelle’s grandmother Vera is implied to be in a relationship with another woman, Sage. Immanuelle herself, hailing from the solidly heterosexual Bethal, is bewildered by this. Her only comparison point is the relationship witches Jael and Mercy, known as the Lovers.

Because of its secondary-world setting, The Year of the Witching is free to avoid the complexities of gender, race and sexual orientation as they have existed between cultures over history, and instead establishes up a straightforward dichotomy: white, authoritarian, straight, patriarchal Bethal versus the non-white, liberal, queer, gender-egalitarian Outskirts.

This set-up could be accused of over-simplification, and certainly, the story is often unsubtle in its depiction of an authoritarian society (“Isn’t it strange how reading a book is a sin, but locking a girl in the stocks and leaving her to the dogs is another day of the Good Father’s work?” asks Ezra, firing the novel’s themes at point-blank range). But ’s pared-down, almost fairy-tale simplicity and heavy usage of familiar coming-of-age character types (the boyfriend, the best friend, the bully) leaves it plenty of room to explore topics that transcend any particular era.

Although Bethel may outwardly resemble a seventeenth-century American settlement, its darker secrets are all too relevant to modern times. During the course of the story, the Prophet turns out to be a child-molester; more than that, Immanuelle finds that he is simply the latest in a long line of predators whose crimes have been covered up:

This was the great shame of Bethel: complacency and complicity that were responsible for the deaths of generations of girls. It was the sickness that placed the pride of men before the innocents they were sworn to protect. It was a structure that exploited the weakest among them for the benefit of those born to power.

The story of Immanuelle’s rebellion against Bethel is not always convincing. One aspect of the worldbuilding – the existence of church-approved white magic, including the Healing Touch and the Gift of Sight – is largely unexplored, and the end-goal is not entirely clear. The novel establishes that good-hearted Ezra might push Bethel’s church in a more progressive direction should be become prophet, but it is hard to envision this when the religion seems to have no principles beyond the oppression of women and the suppression of knowledge. On the whole, however, the story has enough moral dilemmas, twist revelations and narrow escapes to hold interest.

All that being said, the novel’s main draw (it is, after all, mentioned in the title) is the element of supernatural horror. The Unholy Four – Lilith, Delilah, Jael and Mercy – exist outside the binary of good witches and evil puritans. Their backstory establishes them as sympathetic rebels, yet in their current form they are wholly monstrous: ghostly creatures driven by bestial desires, particularly the desire for revenge. The dimension they bring to The Year of the Witching is subtle, ambiguous, even mythic; all desirable traits for a story that often tends towards the simplistic.

The witches are iconic folk horror creations, equal parts spirits of nature and ghosts of history’s victimised women. Lilith, the tall and slender witch-queen, her head fused with the deer skull with which her mocking killers crowned her. Teenage Delilah, corpse-pale and bruise-faced, who dwells in the dark waters. And the Lovers, Jael and Mercy, the first of the Unholy Four to be encountered by Immanuelle, who sees them embracing one another in the woods:

Immanuelle’s knapsack slipped off her shoulder and struck the ground. The women stopped, seized, and detangled themselves from each other, rising from the ground. […] The blond woman stepped forward first, her hand slithering free of her lover’s grasp. She crossed the glade in a few long strides and stopped just short of where Immanuelle stood. Up close, she could see that the woman’s features were mangled—her nose was badly broken, the bone of the bridge protruding into a sharp joint. Her lips were full, if a little swollen, and Immanuelle saw that the bottom ne was split down the middle. Her breasts hung heavy and bare, and her head lolled to one side, as if her neck lacked the strength to hold her skull upright.

The Unholy Four torment Bethel with four plagues, partly overlapping with the plagues of Exodus. First, the town’s water is turned to blood, leading to mass thirst. Next, members of the community are thrown into states of self-harming madness, the effects of which are (like the predatory behavior of the Prophet) amongst the novel’s more disturbingly credible horrors. Plagues of darkness and slaughter follow – although by that point Immanuelle’s rebellion against the church and her activities in the Outskirts have taken centre-stage, the machinations of the witches becoming an atmospheric backdrop until the novel’s climax.

The Year of the Witching demands a degree of patience from its readers, and some may be thrown by the pseudo-historical backdrop and worldbuilding that is sometimes parable-like in its simplicity. The reader who perseveres, however, will find a novel where black-and-white morality is haunted by ambiguities and horrors range from the enjoyably fantastical to the uncomfortably believable.

Immanuelle’s evolution from misfit to rebel is what drives the plot, but the atmosphere of dark magic is what lingers in the imagination.