Welcome to the final post in a series examining the contenders in the main prose categories for the Hugo Awards. So far, the Best Novel selection has shown an interesting set of recurring themes along with some stark contrasts. Two of the finalists, Seanan McGuire’s Middlegame and Alix E. Harrow’s The Ten Thousand Doors of January, both play with the genre of children’s portal fantasies, and although there are clear differences – for one, McGuire is interested in the modern world, Harrow more in history – the two books could almost be companion pieces.

Then we have Kameron Hurley’s The Light Brigade and Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire, two novels of futuristic conflict in which the differences outweigh the similarities. Hurley continues a tradition that dates to the work of Robert E. Heinlein while Martine heads still further back for inspiration, recreating the Byzantine Empire in a tale of the future that absorbs elements from a range of different genres. That said, themes of imperialism and authoritarianism run through each story.

We are left with two more novels. Both are set in the future on other worlds; both are coming of age narratives built around fractured friendships; but beyond that, they are two wildly distinct novels…

The City in the Middle of the Night by Charlie Jane Anders

Sophie and Bianca dream of fighting back against the oppressive society of Xiosphant, a city built by human colonists on an alien planet. When Bianca gets into trouble with the authorities over a minor misdemeanour, Sophie saves her by taking the blame. As punishment, she is exiled from Xiosphant and left for dead in the frozen wastes that surround the city.

There, she ends up face to face with members of a tentacled, pincer-wielding race loosely referred to as “crocodiles” by the human inhabitants, who treat them as animals. But in reality these are sapient beings, ones who rescue Sophie and communicate with her by passing their memories directly into her head. In her time with the aliens she begins referring to them not as crocodiles but as Gelet, a name that means simultaneously mender, builder and explorer.

Sophie’s story alternates with that of Mouth, a young woman born to a nomadic people called the Citizens. But with the Citizens almost totally wiped out, Mouth now wanders with bands of criminals. Mouth’s travels take her to Xiosphant, where she meets Bianca – who believes that her friend Sophie is dead, and who is reconsidering her outlook on the world. Sophie and Bianca are eventually reunited, and Mouth joins up with them; but times are changing, and not all of their ideals and attitudes survive the story intact.

The City in the Middle of the Night takes place on a planet that is tidally locked to its sun, leading to one side being bathed in burning heat and the other left to freeze in perpetual night; the human population is forced to settle in a Goldilocks zone that runs between the two extremes. Charlie Jane Anders puts effort into imagining the culture of a society that exists in endless twilight, with an understanding of chronology different to our own.

For example, Xiosphant’s totalitarian structure is tied to its strict management of time, dating back to a tumultuous event known as the Circadian Restoration. But the split nature of the novel’s planet also serves a symbolic function. Xiosphant is one of two cities on the planet, the other being Argelo; the two have wildly different cultures and are referred to respectively as the cities of dawn and dusk. The authoritarianism of Xiosphant contrasts with the libertine backdrop of Argelo, known for the hedonistic lifestyle of sex and celebrations that it offers to its residents – at least, those affluent enough to afford such an existence.

Above all, the setting of the two cities and their differing societies becomes a convenient means of articulating a complex set of themes relating to tension between individuals and culture. The novel’s characters are regularly confronted with discoveries that turn over their preconceptions, generally through means rather less straightforward than the telepathic communication through which Sophia learns about the ways of the Gelet. During the course of the story Mouth is forced to reconsider her attitude towards the memory of the Citizens, while the loss of Sophia shakes Bianca out of her sheltered student-radical view of society and puts her life on a very different path.

The theme of contrast between personal life experience and cultural narrative-building runs through the book. In the city of Argelo, where the population “grew up reading glossy romances about palace intrigue in Xiosphant”, Bianca regales wealthy locals with tales of her exploits in her home city, including the attempted execution of Sophie. Meanwhile, Sophie resents hearing such a traumatic episode in her life being wheeled out as an adventure story to entertain partygoers.

Mouth has a similar attitude towards hearing the culture of the Citizens discussed by outsiders, and is disturbed when she meets a professor who views the Citizens and their society as an abstract topic for study. She later meets Barney, another surviving Citizen, but an older Citizen who made the decision to move away from the others and integrate himself into mainstream society. He turns out to have a less idealised perspective on his background: while Mouth yearns to find the few remaining fragments of her birth culture as embodied in a book known as the Invention, Barney blithely dismisses the Invention as mere doggerel.

The novel generally avoids dividing these conflicting perspectives into the categories of right and wrong: even the Gelet, who have the ability to keep objective records of events via shared memories, turn out to have a morally ambiguous history. Although the setting lends itself to a simplistic narrative of noble young rebels against a corrupt dystopia, what Charlie Jane Anders instead offers is a nuanced network of ideas that invites the reader to draw their own conclusions.

The City in the Middle of the Night touches upon a range of contemporary topics, from ecological devastation to police brutality, but never offers easy answers. It also leaves room for multiple interpretations. Sophie’s ongoing transformation in to a human-Gelet hybrid can be read as a manifestation of the novel’s theme of culture-crossing; but it can also be read as a symbolic depiction of being transgender – bearing in mind that author Anders is herself trans.

Relevant to today and yet timeless, harking back to decades-old classics of New Wave science fiction and yet fresh and inventive, The City in the Middle of the Night may well go down as a modern classic of the genre.

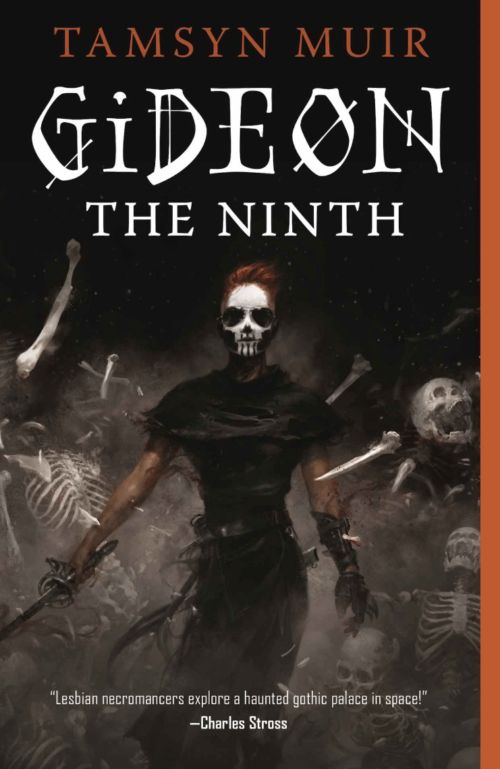

Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir

Gideon Nav does not enjoy her existence in the House of Nine, a society dominated by necromanecers. She even tries to escape the planet on which the House is based, but this effort fails and she remains drudging along as the indentured servant of necromancer Harrowhark Nonegesimus. Gideon’s job is to help Harrowhark fulfil a test that will grant her a promotion in the necromantic ranks; this involves travelling to the First House and completing a series of tasks – which will, in turn, require Gideon and Harrowhark to put aside their utter contempt for one another and work as a team.

The tasks turn out to be challenging, strange, and distinctly brutal. As necromancers begin disappearing one by one, it becomes clear that something more than a mere aptitude test is going on…

Gideon the Ninth has a carnivalesque quality to it. Its necromancers exist in an eternal Halloween or Day of the Dead and the macabre business of raising corpses is treated in a distinctly frivolous manner, with animated skeletons acting as household servants. Like a Goth convention, the novel’s setting is a free blend of influences from different eras: although the society is a spacefaring one that has reached multiple planets, the surrounding aesthetics are distinctly medieval, while the day-to-day technology level is twentieth-century, printed magazines being the main form of entertainment. The central characters themselves are teenagers, and begin the narrative in the familiar teen-comedy realm of bunking off work, smuggling porn magazines and being very sarcastic about each other’s fashion sensibilities:

Reverend Daughter Harrowhark Nonegesimus had pretty much cornered the market on wearing black and sneering. It comprised 100 percent of her personality. Gideon marvelled that someone could live in the universe only seventeen years and yet wear black and sneer with such ancient self-assurance.

In short, Gideon the Ninth takes the planetary romance – that retro-futuristic genre pioneered by the likes of Edgar Rice Burroughs – and makes it Goth.

But the novel is more than merely a sea of rolling eyes and faithful household skeletons. This is also a story about growing up, with the teenage characters being confronted head-on by life’s harsh realities in the form of the brutal deaths suffered by various necromancers in First House. These fatalities also turn the novel into a murder mystery, providing a solid framework for its fantasy elements.

Such a structure is vital, as Gideon the Ninth turns out to be surprisingly complex in its worldbuilding. What initially appears to be an invitingly silly universe of spacefaring, porn-mag-reading necromancers turns out to have an elaborate structure of rules: the characters deal with different types of risen corpse, each with a different type of spirit attached; and they use different forms of necromancy, with different prices to pay. The interplay between the various houses and their respective histories turn out to be similarly intricate, and as the story develops the protagonists uncover a fair number of (the pun is unavoidable) skeletons in closets.

In amongst the skeletal framework of the murder mystery and the pulsating guts of necromantic weirdness, we find the beating heart of the novel: the relationship between Gideon and Harrowhark. “Love-hate relationship” is an easy phrase to write but a harder concept to give life to; Gideon the Ninth takes the time give its principal characters convincingly conflicted attitudes towards one another, arising from a seething cauldron of hormones and social mores and developing into intricate forms over the course of the story.

The first instalment of a projected trilogy, Gideon the Ninth gives us all that is necessary from an opening jaunt in a world of fantasy: a fresh setting, a credible set of characters and a thick veneer of strangeness.

This concludes our series reviewing the 2020 Hugo finalists. The awards will be presented on Saturday 1 August.