Previous issues of John Constantine: Hellblazer have embraced the series’ legacy with open arms. Writer Simon Spurrier, artists Aaron Campbell and Matías Bergara, colorist Jordie Bellaire, and letterer Aditya Bidikar have crafted a story that is not only horrifying but explicitly political; its villains are demons and devils, yes, but aided by the literal powers that run our world’s most corrupt systems.

John Constantine: Hellblazer #6

Jordie Bellaire (Colorist), Aditya Bidikar (Letterer), Aaron Campbell (Artist), Simon Spurrier (Writer)

DC Comics

June 2, 2020

“Quiet,” the series’ standalone sixth issue, is no different. Here, we finally learn the backstory of Noah, Constantine’s new… sidekick isn’t right, as it would imply that the titular Hellblazer intentionally involves him at all, which clearly isn’t true. “Driver” is inadequate, “ward” too caring, “friend” laughable. He’s caught in Constantine’s orbit, anyhow, and this story orbits him.

We know from past issues that there are figures looking out for Noah, distant as they may be. We know, too, that Noah’s mother is in the hospital and he visits her frequently, and that his involvement with the Ri-Boys was to protect her. But we zoom out from that to the hospital itself, a place of illness and injury inhabited primarily by people one their way from one place to another — visiting, recovering, dying.

One figure in particular strikes both the narrator and the reader: a woman in a red dress and thigh-high boots. A beautiful woman, a woman that Noah tries to flirt with. A woman who responds by spitting right there in the hospital hallway, her eyes heavily shadowed. In other contexts they may look sunken or tired — in this one, they look evil.

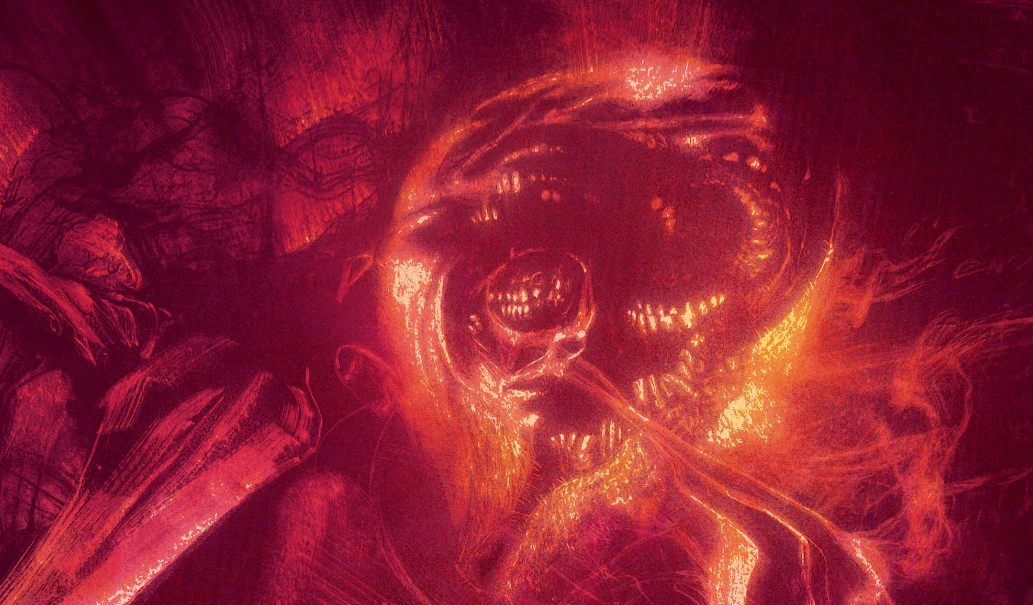

Campbell is an exquisite artist, but one especially gifted at horror. His demons are swirling, formless things, masses of teeth and tendrils of energy brilliantly colored by Bellaire. The two work in a way that is more or less guaranteed to give the reader nightmares, particularly as the demons slip too easily back into human shape, malice in their eyes and smiles. Their shapes twist, dissolving like ink in water, but even at their most abstract you can see their greedy, grasping hands and many, many teeth.

The woman, the ghost, is not just a ghost. Like so many Hellblazer villains, the things that haunt and torment the characters are echoes of reality. Here, home-grown British xenophobia manifests as a red-coated woman made of hatred.

Throughout the issue, we see the internal stories of several characters, how the systems have failed them, how they have failed one another and themselves. At the center of everything is this seething spirit of hatred, itself the product of spite and loneliness and fear, and though it, too, is a victim, it targets those who are even more vulnerable, those who aren’t British.

This idea of nationality has been a point of concern for me throughout the series. At no point does John Constantine: Hellblazer suggest that xenophobia is a good thing, but repeated references to Britishness seem to go unchecked. As I mentioned in my review of issue four, Tommy Willowtree’s use of “foreigners” to describe those attacked by the crows at the Tower of London gave me pause. In this issue, we have Constantine asserting (and being correct) that the demon won’t attack him because he’s British. But Noah, too, is British — British and Black. His mother is described as “in every respect, a Brit.” So why is Noah in danger?

There’s an obvious answer — that the ghost doesn’t care at all about nationality and cares about upholding the idea of Britishness as whiteness — and a more insidious one. I was leery of Willowtree for a variety of reasons, including his use of foreigners to describe characters of color who may very well have been British, but nothing untoward ever came to light.

Is Constantine wrong in assuming that it’s Britishness, not whiteness, that protects him? As of the end of this issue, we don’t know. It’s a theme that has bubbled up throughout the series but has yet to be addressed. Why was the racist at Peckham Rye so quick to believe Constantine was on his side? Why does the use of “foreigners” go unquestioned?

I hope — and I really do hope — that the reason is that part of Constantine’s growth must hinge on his acceptance of his complicity, that eventually he will need to recognize that it’s whiteness, always, that protects him. Otherwise, there’s a problem at the core of this series; that the creators don’t realize that either.

From everything that the series thus far has done to call attention to injustice, I don’t believe that’s the case. But John Constantine: Hellblazer has a chance to be a strong, biting narrative about complicity in racism, xenophobia, and violence, and I very much want it to get to that point. With each issue that goes by without a questioning whiteness itself, however, I grow a little more skeptical.

There’s something else, too. Without spoiling the issue, “Quiet” hinges on a moment of intense compassion from an oppressed person toward an oppressor. This is in conversation with one of the issue’s other themes—one of recognizing the radical power of compassion, even in the midst of oppression.

Do me a favor? Spread this far and wide. It's not often John Constantine speaks for all of us, but just this once…? #NHS #Hellblazer pic.twitter.com/p8bqWC3Zw3

— Simon "Si Spurrier" Spurrier (@sispurrier) March 27, 2020

I like this; I really do. I live in America, which needs no further explanation other than that it’s often hard for me to fathom the cruelty holding together the systems of this country. But at the same time, all of these questions of whiteness and forgiveness and compassion are tangled up in the extremely white liberal idea that we can simply love xenophobia away, that centuries of institutional racism can be erased with a moment of empathy. Not only is that demonstrably false, but it also places the onus of solving xenophobia on those who are oppressed, as if oppressors have simply failed to see the humanity of those they oppress rather than actively denied it.

I don’t believe that this is what the John Constantine: Hellblazer team believes, but nor do I yet have the textual evidence to say that they do not. If John Constantine is truly to become a better man, as the Sandman Presents issue led us to believe, the examination must go deeper, to more challenging places. We know that Constantine is often a terrible man — the narration tells us this outright, comparing him to a self-hating virus and a parasite — but if he is truly to grow throughout this story, he must fight not just the powers that benefit from xenophobia, but also the ways he enforces and benefits from whiteness.

This may seem like a lot to ask from a comic where one character does pun magic and another is repeatedly said to look like a scrotum, but the heart of Hellblazer has always been a deep and uncomfortable, sometimes clumsy, examination of political issues. Constantine’s backstory comes from his time in a punk band and some of the early issues focused on the aftermath of the Vietnam War and gentrification. It’s time for this series to go deeper, to really get its hands dirty and begin to unearth the evil roots growing in its characters, not just in the systems that influence its villains.