Whilst researching the history of Clyde Fans and its author, I found that the Guardian ran two separate reviews of the book a week apart this past spring. Both were glowing pieces hailing the book’s somber melancholy, one going so far as to praise its author, the mononymous Seth, as a genius. Other outlets have praised this book as a ‘masterpiece,’ a ‘magnum opus,’ and a host of other superlatives.

Folks.

Clyde Fans

Seth

Drawn & Quarterly

April 30, 2019

Clyde Fans is the five-book story of a family that once owned a business. Each book was released separately over the course of twenty years, with the final, collected volume available in a slipcased hardcover last year.

The family name isn’t actually Clyde. It’s Matchcard, but the business is named after the patriarch. In the first chapter, set in 1997, we meet Abe, the elder son and last living member of the Matchcard family. Abe is old, and tired, and lonely. He grieves for his lost brother Simon and speaks only to the reader as he moves through the empty, faded house that sits above the long-closed store. The first chapter is ninety six pages long, and in that time we meet no one else save through Abe’s recollections of them, as he details the long and winding story of his family, the store, and his role in both. If Clyde Fans is a masterpiece, it’s one of irony in this chapter, as Abe’s story begins with a lecture on how to be a good salesman that then winds its way into the rest of the tale. His chief lesson is that you have to be interesting if you want to make a sale, and while I certainly buy that (heh), it’s hard not to scoff at the delivery mechanism; an old, sad man clinging to the memories of his life. I cannot think of a delivery mechanism for a story that I am interested less in.

Abe is also full of the kind of opinions one hears often in older generations; how he doesn’t understand the music today, how folks these days will just buy cheap junk over and over again instead of a quality product that lasts. He’s a well-realized character in this regard, I suppose, but that’s hardly deep praise–media has given us an abundance of his type in both fiction and reality. It feels a bit like…well, choosing the easiest starting point for a character one can get.

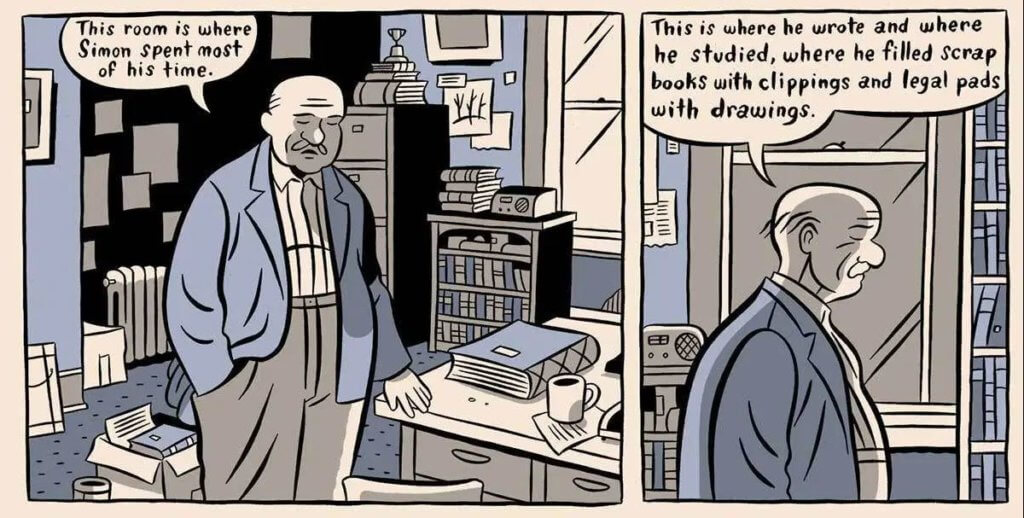

We learn some of the story of Simon as Abe moves through his soliloquy, how he was an anxious man who didn’t function well in public. He was writing a book, Abe says, about novelty postcards. As it neared completion, someone else published a similar book, and Simon’s anxiety and impostor syndrome defeated his ability to complete his life’s work.

We don’t learn much more about Simon until book two begins. This one drops back forty years to 1957, as we follow the man (who looks like the author) on his first, disastrous, and only trip attempting to sell the family’s product in a new town. Simon’s plight is sympathetic; we have all felt the nervousness before putting oneself on show, but that sympathy evaporates when, on meeting a fellow salesman, we see Simon come away with a knick-knack that just happens to be a racist caricature of a Black man that pops up, spring-loaded, out of a tin watermelon. It was at this point I put the book down and cursed aloud.

Why the fuck do we keep letting men like this make art? There are so many artists, so many creators out there with the ability to make work that is forward thinking, intellectual, intersectional. So why, here in the year of our Lord two thousand and nineteen, are we holding up a slipcased, hardcover edition of yet another white man writing sad comics about how the past was better? We get it, you liked it better when minorities were even more at risk than they are now. We get it! Fuck off. Seth, real name Gregory Gallant, could have done so many things in telling this story, and instead he chose to weave the tale of two white brothers feeling fucking sorry for themselves whilst casually offering a bullshit racist depiction as its only fucking representation of a person of color thus far in to the tale, one hundred and forty eight pages in. WE GET IT, GREGORY, YOU DON’T KNOW ANY BLACK PEOPLE.

Book three takes us to 1966, where–finally–we meet the matriarch of the family. She’s seen exactly one mention up until now, in book one, and only as ‘mother’. Simon is taking care of her, in the house above the shop, as she fades into senility. We’re ‘treated’ to Simon’s inner monologue as he mopes around the house, and he at least has the grace to call the toy he bought a decade prior “horrid,” but what does that mean? Nearly fifty pages later, there still hasn’t been an actual Black person (or indeed one of any other ethnicity) in the story, just that one racist depiction. That toy makes another appearance soon in the course of a dream Simon has, before we later see Simon in his office with a whole shelf of toys and a completely different racist one. This one talks to him. We can’t see what it’s saying, of course.

Eventually, the Matchcard matriarch has to go into a facility for care of her dementia. It’s here that we finally, finally learn her name, when an attending nurse asks if it’s all right to call her ‘Lily’. We’re on page 271, folks. Neither Abe nor Simon has mentioned her by name in all of these pages, all of these years. She’s simply the ‘mother’. The archetype. A perfect and attentive thing in the depiction of Simon’s youth, a decrepit and illucid one in his adulthood. She has, after all, outlived her usefulness, and so her agency, her identity, is unimportant until the moment she leaves the picture. “Hey, who was that old lady anyway? Guess I’d better give her a name.”

Simon’s second racist toy is silent now, no words of comfort for him. He calls this one awful and questions why he bought it. A great question! Here’s a better one: why did you buy two?

Book four moves us to 1975, where we finally have an involved scene with Abe again, as he’s…closing a factory in the face of a worker’s strike. This was foreshadowed in the first book; in 1997, he speaks extensively about the company going out of business due to the rise of air conditioners and his own failure to move Clyde Fans into that market. After he signs the papers to do so, he has to drive out past his own picketing workers. They watch him leave in dismay, and then we’re treated to another rambling monologue of Abe’s, this time as he lists the women he’s slept with, cheated on, gaslit, and left. It’s a curious thing. I have to wonder, is Seth deliberately painting pictures of the Matchcard brothers as contemptible figures? They’re both atrocious in entirely unique ways, which is…I guess…a kind of success in craft. It would be more rewarding to read, I think, if the author didn’t treat the few women who appear in the story like props, playthings for the Matchcard brothers to project their horribleness onto. It’s..honestly sort of sickening to read.

The final chapter of this utter slog of a book deposits us back in 1957. Here we’re shown the manner in which Simon spent the last night of his sales trip to Dominion. He sits beneath the stars having some kind of epiphany about the decay of the world, the natural course of entropy over time. It’s a strange thing, to witness the profound effect this waking vision has upon him; when he finally leaves to head home, he’s smiling, watching the land roll by from the window of his train seat, instead of hunched and sweating nervously due to the press of people around him.

We know, because this is a story told out of order, that Simon dies old, alone, and sad, in the house above Clyde Fans’ original storefront. To end on this, his last moment of clarity and contentedness, is surely meant to be some sort of bittersweet thing–as Seth writes, “a frozen life.” It’s not really, though–it’s just bitter. Simon goes home having learned nothing real or substantial; he merely wastes away talking to his racist toys whilst his brother gives up on him.

This book, 478 pages long, starts with a joke about salesmen. It lasts hours, and ends with the world’s most bland conclusion, that time is a fleeting thing. I suppose it’s correct; I’m never going to get what I spent here back. A good joke, Seth.