The Tango series is perfectly escapist comics, with plenty of welcome cinematic parallels. If you want to get away for a minute, and you enjoy spending time with ideas of men, this is a book for you. Compared to aesthetically similar books it’s lighter than The Killer (no philosophical challenges here, though it’s not without discussion of ethics; they’re simply less integral) and less rigorously based in intrigue than Lady S or IR$—just a fun, breezy read about principled men outside of the law working against the wicked and corrupt forces of organised crime.

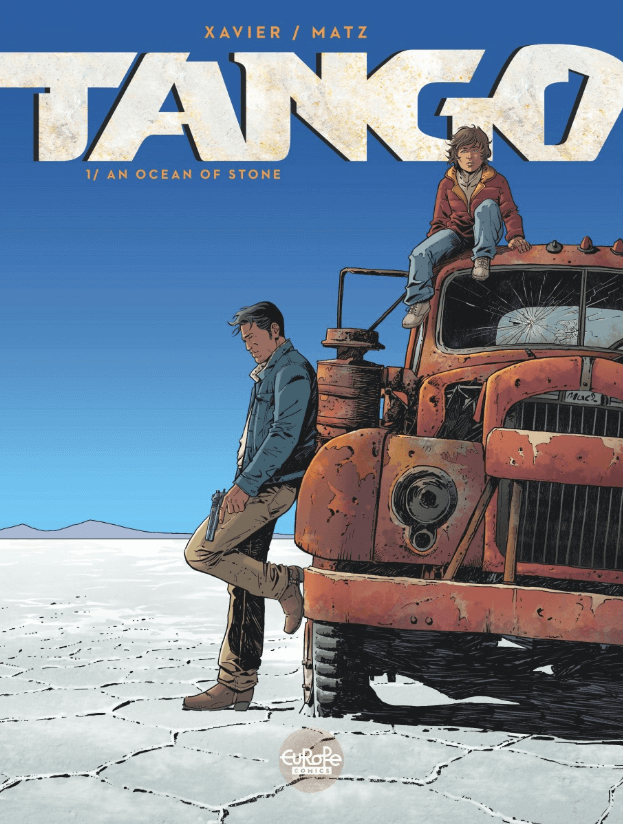

Tango volumes 1-3: An Ocean of Stone, Red Sand, No Safe Harbour

Jean-Jaques Chagnaud (colourist), Matz (writer), Philippe Xavier (artist), unknown letterer & translator

Europe Comics

March 4, 2020

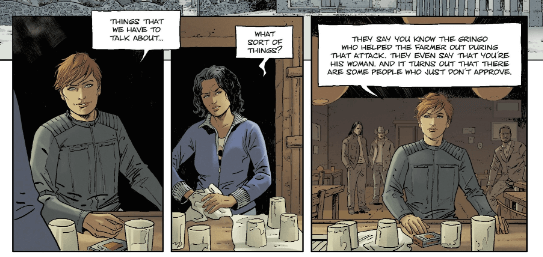

Tango and his eventual companion Mario take on those who victimise the weaker and the settled, when they’re threatened by the roaming cruel. They aren’t against friendly association with people who have been “the bad guys,” as long as they’re not being them right now, and they have both previously worked with and parted ways from law enforcement organisations. They’re certainly not averse to shooting someone dead if that someone might shoot first. They like friendly sex with beautiful women, and following their own bliss. Action comics, pure and simple. The images in this article are all from the first volume, An Ocean of Stone.

In his recent EuropeComics interview, artist Philippe Xavier mentioned Jim Lee pencilling Omega Red in X-Men, 1992, as a seminal influence on his life as a cartoonist. This isn’t inevident—beautifully executed pages of semi-flamboyant masculine violence follow us about every turn of the page—but it’s less obvious than the other American reference Xavier and Matz (scripter) have according to that same interview. Writer-director Shane Black’s (Lethal Weapon, The Last Action Hero, Iron Man 3, etc etc) hallmarks are all over this comic: the odd-buddy dynamic, the clever and funny banter (though even in translation the structure of the dialogue here feels extremely French, which makes a nice change), the lack of fear both in the characters and the narrative’s caper violence. Even the hot hot sun and sprawling vistas recall the pleasures of knowing one guy is too old for this shit and the other will get him into it anyway. Small-part people die, often, but that’s not really the emotional content of the action: the emotional content of the action is the adrenaline that hits as you live vicariously, how nice it feels to watch people having a whale of a time surviving unlikely things. The emotional content of the framework for the action is the warmth and the good humour that goes beyond technically executed line exchange. At the end of the first volume, an apparent enemy turns around his opinion on Tango and reveals his own similar perspective on life, love, and law. When Tango finds himself at a very loose end with nowhere to go Mario offers him shelter in his own home and property, and from then on these two characters share the book as they share a boat.

Another similarity to Black’s filmography is the now-you-mention-it lesser interest in women’s participation. I’ve been a Shane Black fan all my life, but he’s still in my bad books over Steven Wilder Striegel—it’s pleasant to find a comic that reproduces and remixes these enjoyable aspects of his work so I don’t miss revisiting it too much, though (now that I mention it) also a little irritating to notice it reproduces the same incomplete (I know about The Long Kiss Goodnight very well, thank you) but present (I also know about the bulk of his oeuvre) disinterest in sustained female perspective that I assume relates to Black’s ability to assume his friend didn’t do anything that bad when he was convicted as a sexual offender.

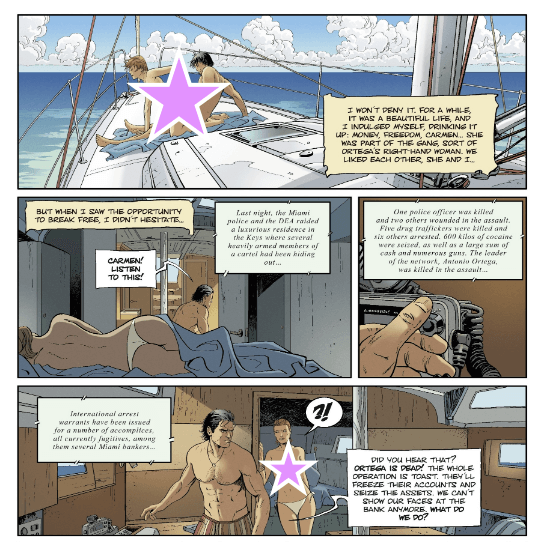

To be clear: I enjoyed reading Tango, enough that I read all three available English-language volumes in one go, and if you avoid books because they have proactive sexist content you can read this one quite happily. The worst Tango does to women in in the early pages of the first book, where he thinks to himself (really to you, the reader-as-confidant, in narrative captions) how glad he is that his girlfriend is a widow, and that she was widowed before she had children to get in the way of their sex. He thinks this while they’re having said sex. It’s fairly tacky and (with a scene of Tango pissing directly on a lizard) contributed to my early sense of this comic as a Tarantino/Rodriguez style “violence ballet.” But as a character beat it’s not repeated, and as a comparison it wanes. Matz and Xavier were a new creative partnership as they made this book, and my impression is that they firmed their vision as they worked. The earliest pages seem the least defined… and that’s fine.

Tango is a Belgian-market comic, translated to English and currently available in its first form and language in four volumes. The release lag of one year is not notable in its own right, but when looking for cues one might think it actually seems a little longer than that. While these characters have modern technology such as phones that can take texts this is only relevant when one of them receives one during a tense, hidden firefight—none of them are interested in smartphone use like you or I might be; nobody mentions any apps or spends leisure time online. It may or may not be down to style geography, or to the age and tastes of Xavier himself, but there’s a light sense of fashions aged. As this applies very slightly to the titular protagonist (he could have dressed anywhere between 1995 and now) and not at all to his number two Mario (a moustachio’d man who loves polo shirts is a man dressing outside of time) it only prods the mind when one looks at what the women are wearing.

Even then, it’s negligible, as they don’t feature too greatly and avoid statement pieces that tie too tightly to era—only pedantic viewers, such as myself, are likely to quibble. They wear things that women in action-edged American television have been wearing throughout the last decade, and prior: practical but form-fitting garments, usually with a shirt hem that hits at lowrise over midrise trousers. It’s not exciting, but at least it’s neutral. Once there’s a strip of abdomen showing between the hem of the tank top and the waistband of the trousers, under an open flannel. It’s not that people don’t wear this, it’s just it’s not really the zeitgeist.

Or, sometimes, as above, the women are near-naked for sexual purposes. When I say “sexual purposes” I mean that their purpose in being naked is to have or have had reciprocal sex with Tango in a scene rather than that their purpose is to bodily decorate a scene that’s, in the diegetic sense, about something else. Not only do they seem basically active but their nudity is usually accompanied by an almost as nude, handsome man. Not perfect parity, but OK.

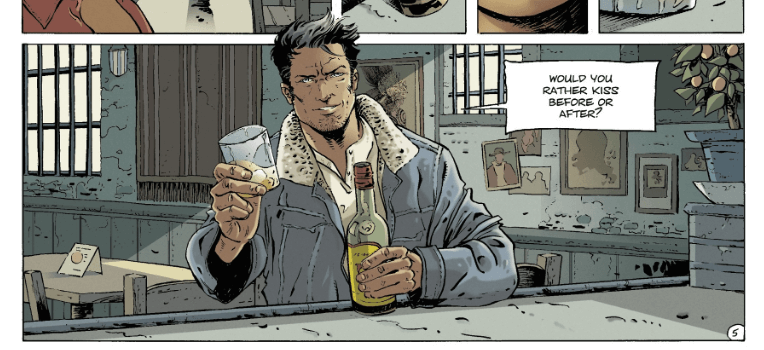

Tango himself is a compelling visual construction. He’s your averagely chiselled, muscular dude but his construction is detailed beyond those basics. During the colouring process light and shadow are always used to give shape to his lips and there is always an implication of motion and “readiness.” This has a lot to do with Xavier’s dedication to making hair look roilingly fabulous—that, certainly, is a key tool in the Jim Lee creative arsenal. It’s apparently very easy for men to forget that men drawn with interesting hair, hair with texture and apparent movement, hair with implicit physicality, are enjoyable. But Lee doesn’t forget it for a second, and neither does Xavier: combined with Tango’s fluffy collar or his casually stretched raglan-sleeve graphic shirt or the scrubby hair marks that adds depth to the curves of his pectorals, you have a hero that seems eminently touchable. Naturally this enhances the feeling of proximity to adrenaline.

Like many EuropeComics of this essential genre, Tango has a high number of panels to page and a quite rigid adherence to panel form. It’s all rectangles (even lettering), with very little (even lettering!) escaping from the outline or even butting up against it. Panels are frames, action is framed—we look through the page to a parallel world caught in frozen moments. With the barest of exceptions, there are no motion lines beyond dust stirred up or blood that’s spraying, in patterns these would naturally take, and very few sound effects. Guns go POW, a smashed cup that’s the focus of a panel goes KRASH, and that’s about that. Thanks to well-judged focus and depicted physics this doesn’t make Tango a staid read, but an additionally tense one. As the subject matter is not structured to be upsetting it’s not stressful. Just a good time.

I’m looking forward to volume four.

A brief gallery of exceptions, and what they do