With the short stories, novellas, collections, and anthologies dealt with in the first and second parts of this series, all that is left are the novels. So, join me as I take one last trip through the inaugural Splatterpunk Awards’ list of the most depraved horror fiction of 2017.

Editor’s note: Once again, this post bears a hefty content warning for graphic descriptions of fictional violence, including various forms of sexual violence.

White Trash Gothic by Edward Lee

The main character in this novel is an author suffering from memory loss. One of the mementos he owns from his now-forgotten past is a document that he typed out in a remote West Virginia motel more than twenty years ago: the first page of a novel entitled White Trash Gothic. In the hopes of regaining his lost memories, the Writer (the only name the narrative uses for this character) heads off to Luntville, West Virginia to find that fleabag motel. Along the way he is haunted by bizarre dreams that hint at all manner of sinister, possibly supernatural, events in his past—but hey, what’s a novelist without inspiration?

While this is the first novel in a prospective series, White Trash Gothic picks up a number of threads from Edward Lee’s earlier works. The character of the Writer, along with his fateful trip to that motel two decades earlier, turned up in Minotauress. Fans of Lee will also recognise Luntville and its local legends, such as serial rapists Dicky and Balls and the semi-demonic killer known as the Bighead, from the author’s past forays into gross-out horror.

The main concern of White Trash Gothic is the collision of the would-be highbrow with the lowest of the lowbrow. Identified by his editor as “the prodigal of the neo-post-modernist lit scene,” the Writer hopes to become the next Kafka or Dostoevsky, and treats those around him as little more than raw material for his prose. His attitude towards lower-class Luntville is overwhelmingly condescending:

“What happen after that? Well, I kin tell ya what my daddy say. He say ever-thing was beautiful until, well, until Dicky Caudill’n Balls Conner was born. It were like Satan himself just up’n take a shit on this town, and his two biggest turds was Dicky’n Balls.”

An exceptional lower-economic hinterland allegory, I’d say, the Writer reckoned.

As the novel progresses, this highfalutin fellow is confronted with every conceivable stereotype of the American backwoods (“I thought I’d seen everything with the Cunt Kicking Contest, the Therm-O-Fresh, and the pregnant woman being force-fed horse sperm,” he thinks to himself at one point). In Luntville, frontier justice mixes with depraved hedonism. Criminals such as drug-dealers are not only executed without trial, they are liable to end up as props in snuff videos. The Writer himself becomes an unwilling performer in one such clip, after being drugged into performing an act of necrophilia while wearing a Munsters mask. As he has no memory of any previous sex, he is left with not only the revulsion of having committed the act, but also the lingering fear that he might have lost his virginity to the cadaver.

And yet, the Writer’s descent into this cultural abyss is followed by a soaring rise.

While Dicky and Balls are long since dead, the locals feel that their curse lives on, as signified by the pair’s battered old car that still lies by the roadside. However, the people of Luntville also believe that someday, a stranger will come to town, sit in that car, and get it to drive. Like Arthur pulling the sword from the stone, this will signify the arrival of a heroic saviour who will finally rid Luntville of its curse. The Writer, intrigued by this local modification of Arthurian legend, decides to try and start the car… and succeeds, thereby establishing himself as The One who will save Luntville!

White Trash Gothic contains layer upon layer of repulsiveness, with just about every chapter including some combination of torture and/or sexual degradation and/or bodily fluids, but it also has layer upon layer of irony. The Writer is an avatar of Edward Lee himself (although we should be careful about confusing a fictionalisation with the real thing, something underlined when the story delivers an outrageous reimagining of H. P. Lovecraft as a he-man sex machine). The first page of Lee’s novel is also the first page of the Writer’s novel, White Trash Gothic. The Writer’s protagonist, Nikoff Raskol, could therefore be an avatar of an avatar—which may have something to do with the fact that the Writer is stalked through Luntville by a doppelganger of himself as he appeared some twenty years beforehand.

With its opaque allusions to Lee’s earlier work and multiple dangling plot threads that will (presumably) be tied off in the sequels, White Trash Gothic doesn’t work particularly well as a self-contained novel. But when approached less as a novel and more as an intricate assemblage of shaggy dog stories, this book is a pretty impressive piece of work.

Exorcist Falls by Jonathan Janz

Exorcist Falls is the sequel to Jonathan Janz’s 2014 novella Exorcist Road, a reprint of which is included in the book. The plot closely follows the events of Exorcist Road, making it impossible to discuss in detail without spoilers for the earlier story.

With that warning out of the way…

In Exorcist Road, young priest Father Crowder helps to exorcise a demonically possessed teenager named Casey. Meanwhile, a whodunit is going on in the background: a serial killer whose MO is the murder of sixteen-year-old girls is loose in the town. During Crowder’s battle with the demon, the evil spirit manages to manipulate the priest into thinking that his mentor, Father Sutherland, is the Sweet Sixteen Killer. The resulting conflict ends with Crowder pushing Sutherland out of a window, a fatal fall that Crowder manages to pass off as suicide. Only too late does he realise that his mentor was innocent, and that the true killer is police officer Danny Hartman—who also observed the exorcism and Crowder’s slaying of Sutherland. “We all have secrets… I’ll keep yours if you keep mine,” Hartman tells him.

Once the exorcism is over, Crowder has more than innocent blood on his hands. He is the new host of the demon Malephar, and is forced into an unholy pact with the spirit that will allow him to live so long as he does not expose Danny Hartman as the local serial killer. This is the sticky situation in which our conflicted protagonist finds himself at the start of Exorcist Falls.

In some ways, Exorcist Falls has the feel of a superhero comic (the grim-and-gritty variety, needless to say). Playing host to Malephar grants Crowder some bona fide superpowers, namely Wolverine-like healing ability and access to the memories of others touched by the demon, including arch-enemy Hartman. The story also sets out the rules of Crowder’s pact with Malephar with the same clarity that a superhero comic would use to establish Superman’s weakness to Kryptonite or Batman’s aversion to firearms. While Crowder is barred from taking on Hartman directly, he does get to flex his demon-powered muscles against lower-level wrongdoers.

Bur Exorcist Falls is not, at its heart, a power fantasy; rather, it is a puzzle. Crowder cannot unmask Hartman directly, as when he starts to get too close to the line, the demon drives him into acts of self-harm (the novel contains a particularly harrowing and drawn-out scene of dental injury). It is therefore up to Crowder to find a way of exposing the murderer indirectly, and hope that his body and his conscience both survive the ordeal. All of this culminates in a killer double-whammy of a twist ending.

Spermjackers from Hell by Christine Morgan

After playing a video game featuring a sexy devil lady, a group of randy young dudes decide to summon a succubus of their very own. What they inflict upon the world is a creature that, in its true form, resembles nothing so much as a big, repulsive slug—a long way from the curvy babes of gamedom. But the succubus is capable of taking on other forms through the power of illusion, fulfilling whatever fantasies its victims may harbour. And as it happens, all of this is taking place in a town where the people harbour a pretty lurid range of fantasies…

While Spermjackers from Hell is built around a one-note joke, it’s smart enough to realise its own limitations and find an inventive way to work with them. Just as the frat-boy japes of the (largely interchangeable) protagonists start to outstay their welcome a short distance into the novel, Christine Morgan deploys her omniscient narrator. Suddenly, everything becomes a whole lot more meta, as in the chapter where the narrator explains why there is a lack of children in the town—and then explains the reason behind this creative decision:

Because, see, this story’s going to get all nasty with sex stuff, dubious issues of informed consent, nocturnal dream-demons and the like — it’s a succubus book, here, people, what do you expect? And having a lot of younger characters around would just make everything a little too icky and weird. We have some standards, thank you very much!

So, about that dogfucker.

At which point the novel descends into a gleeful description of bestiality.

This approach allows the novel to analyse the male sexual fantasies that it exploits for its storyline, as when the narrator outlines the appeal of the mermaid legend: “big bare buoyant boobs, flowing gorgeous hair, and all the fellatio a guy could ever hope for, but without any of that squicky vagina business.”

Serving much the same function (to the narrator, not the mermaids) is Beth, the token girl in the otherwise all-male gang of demon-summoners, who is always ready to cast a wry eye over the predilections of her horndog friends. During the course of the novel the succubus masquerades as Beth, a plot point that Morgan uses as an excuse for more meta commentary. Male sexual fantasy, and sardonic appraisal of male sexual fantasy, thereby become one and the same.

Spermjackers from Hell is an utterly filthy, lurid, shameless exercise in gratuitous exploitation that turns out to have a surprising amount going on between its ears.

The Hematophages by Stephen Kozeniewski

Paige Ambroziak gets a new job on board a spaceship, and finds out that the crew’s mission is to locate the wreck of the Manifest Destiny: a ship that mysteriously vanished and passed into legend, immortalised in literature and film.

Along the way the ship has a run-in with a band of “skin-wrappers.” These are people who, faced with terminal illnesses, underwent a drastic treatment that involved having their skin removed and turning to lives of piracy, stealing organs to prolong their existences. But this is only the start of the problems faced by Paige and her crew…

The Manifest Destiny, it turns out, is inhabited by the descendants of its original crew. These people have legends of their own, including the belief that the ship was scuppered by a disease that warped the minds of its victims, turning them into saboteurs. This leaves the would-be rescuers with a dilemma: if such a disease ever existed, could it still be a threat? Can the population of the Manifest Destiny be allowed out without the risk of this infection spreading?

Then the truth comes out. The “disease” is, in fact, the work of a lamprey-like alien parasite that burrows into its hosts’ brains and controls their bodies. One by one, Paige’s fellow crew members begin falling to the hematophages.

The Hematophages is, as scarcely needs to be pointed out, a space-age update of the vampire theme. While the extraterrestrial parasites resemble something out of Alien, their effect upon their victims is more in line with Hammer horror: the host will retain enough of their own personality to pass unnoticed but their motives will be twisted, so that a lover becomes a deadly tempter. “We feel like a villain in a third-rate entertainment fiction,” opines a woman controlled by a pair of hematophages.

The novel is interested primarily on how its aliens affect relations between the human characters. Paige, her crewmembers, the inhabitants of the Manifest Destiny, even the captive leader of the skin-wrappers are all thrown into turmoil. Friendships break down, and strange new alliances are formed. The skin-wrappers, introduced as beings of horror, reveal a more pitiable side to Paige. Even the hemetophages themselves are partly sympathetic, as they are ultimately reacting to a near-genocide brought about by the tellingly-named Manifest Destiny.

Stephen Kozeniewski is canny enough to avoid launching straight into this knotted tangle of twists and turns. The Hematophages starts out as something of a spaceborne office comedy, with Paige and the other women (the novel takes place in a future where the male sex is extinct) treating their mission as just another job, albeit one with an oddly secretive aspect. Bit by bit, however, the gorier elements of the story make themselves evident. When Paige arrives at the homeworld of the hematophages, a planet covered in an ocean of blood, it provides a neat metaphor for the narrative trajectory of the novel as a whole.

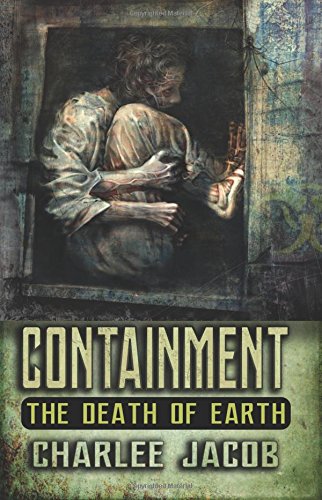

Containment: The Death of Earth by Charlee Jacob

Reading through the Splatterpunk Awards, you will by and large find the sort of thing you’d expect to find. Novels about demonic possession, short stories about necrophilia, anthologies about torture and degradation… and then you come across something like this.

Containment: The Death of Earth is set against a backdrop of conflicts both heavenly and terrestrial. The former is represented by a demon-spawn boy who is being reared by a brutal angel, kept in a building and taught about the outside world from various books. The latter is represented by Louise, daughter of a Sudanese rape survivor named Shimani. Together, the two travel across a war-ravaged Africa, with Louise having visions of a “mango woman” who weeps orange tears. The years pass and the two children grow up as the Earth trundles towards the Apocalypse.

The novel recalls the magic realism of Salman Rushdie, with portrayal of real-life brutality sitting alongside dreamlike symbolism and a general tone of detachment throughout. Billing itself as a “novel and grimoire,” the book confronts the reader with its own artificiality, switching abruptly from straight narrative fiction to discourse on topics as varied as Biblical apocrypha and genetic science.

Containment makes no effort towards being an easy read. Whenever the narrative looks as though it’s about to slip into a comfortable genre formula, Jacob suddenly throws in a chunk of formalistic experimentation, be it an entire page devoted to listing the names of various demons or a rambling digression from the omniscient narrator. The novel depicts the world falling into chaos, and fittingly, it is itself an intentionally chaotic piece of work.

Those looking for more straightforward horror should probably look elsewhere, but those looking for something a little out of the ordinary will definitely find it right here.

Final Thoughts

So, that’s the inaugural Splatterpunk Awards. With all of the finalists covered, all that is left is the question of who will be winning. Well, for what it’s worth, here are my picks.

For Best Short Story, while Bracken MacLeod’s “Extinction Therapy” is the most thought-provoking, I would go with Matt Shaw’s “Melvin” as my top choice. Short, succinct, stomach-churning and yet satisfying—what more could I ask for from a Splatterpunk short story?

In Best Novella, while Edward Lee and Ryan Harding’s Header 3 deserves recognition as the single most comprehensive litany of atrocities in the category, my pick for the strongest contender would be Somer Canon’s Killer Chronicles. The book’s combination of a quirky, even whimsical sense of humour alongside an exploration of humanity’s darker corners is something that has remained in my mind since I read it.

In my view, the clear winner of Best Collection is—with no disrespect to the other finalists—Jack Ketchum’s Gorilla in My Room. It’s a slim volume packed with powerful moments, and it serves as a shining testament to a departed talent. Best Anthology is a tougher choice, given that all of the books go over similar subject matter, but I would pick The Year’s Best Hardcore Horror Volume 2 as the standout thanks to its relatively subtle approach.

Finally, we have Best Novel. Containment deserves praise for its experimentation; Spermjackers from Hell is a solid laugh; White Trash Gothic is Edward Lee at his most Edward Lee-ish; and Exorcist Road has its share of inspired twists. But the novel that engaged me the most is Stephen Kozeniewski’s The Hematophages, with its successful melding of numerous genre elements to create a gripping tale set in an intriguing science fiction universe.

Those are my thoughts. We shall find out who the winners are when the Splatterpunk Awards are handed out on August 25th at KillerCon Austin!

Note: The original version of this article repeated a mistake from the KillerCon Austin website stating that the awards will be presented on the 28th of August. They will in fact be presented on the 25th.