My Horse Prince

Umaya Co.

December, 2016.

Let’s get this out of the way: My Horse Prince is not a good game. It might even be a bad game, like a clicker crossed with a dating sim and made purely for those sweet free-to-play ad dollars.

It’s not fun. There are no stakes. It has no end. I spent my last few days with this mobile game begging for it to be over so I could start writing about it, because, despite my lack of interest in the gameplay, there is something deeply interesting about My Horse Prince. Namely, its weirdness.

The premise itself is what sells it–you play the typically blushing maid hero, only instead of a slew of cute boys to choose from, you only have one, and he’s a horse with a human face. There’s no Beauty and the Beast reveal in the end; Yuuma begins as a horse with a human face and ends as a horse with a human face, and your protagonist (Umako is her default name, so that’s what we’ll use) falls in love with him despite, or perhaps because, of it.

The premise itself is what sells it–you play the typically blushing maid hero, only instead of a slew of cute boys to choose from, you only have one, and he’s a horse with a human face. There’s no Beauty and the Beast reveal in the end; Yuuma begins as a horse with a human face and ends as a horse with a human face, and your protagonist (Umako is her default name, so that’s what we’ll use) falls in love with him despite, or perhaps because, of it.

That’s it; that’s the whole game. The conceit aside, My Horse Prince becomes a tedious exercise in clicking on carrots, treadmills, broken water lines, and other objects to progress. To fill Yuuma’s energy meter, you must answer his questions and use that energy to click more things and move the story forward.

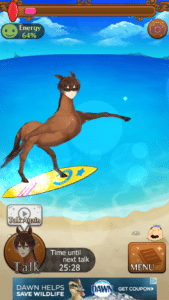

It’s obvious from the beginning what will happen–Umako and her horse prince will end up together, despite the odds. What draws us along is the promise of more weirdness to come. It builds on itself, constantly pushing your threshold for what weird really is. Is it a human-faced horse? Is it that same human-faced horse on a surfboard, cutting green onions, performing at a rock concert?

The industry’s biggest games are those that play it safe. Take one grizzled white male hero, give him a gun and a lady to save or avenge, and you have most of gaming’s biggest blockbusters. My Horse Prince will never compete with those in terms of revenue or exposure; like Hatoful Boyfriend, its legacy will be one of sheer strangeness. Most people who play games like these will not make it to the end as the gimmick wears off, and, in fact, My Horse Prince doesn’t end; it cycles back into itself, trapping Umako and Yuuma in an unending, heaven-esque loop of training.

The industry’s biggest games are those that play it safe. Take one grizzled white male hero, give him a gun and a lady to save or avenge, and you have most of gaming’s biggest blockbusters. My Horse Prince will never compete with those in terms of revenue or exposure; like Hatoful Boyfriend, its legacy will be one of sheer strangeness. Most people who play games like these will not make it to the end as the gimmick wears off, and, in fact, My Horse Prince doesn’t end; it cycles back into itself, trapping Umako and Yuuma in an unending, heaven-esque loop of training.

But it’s weirdness, more than anything, that the gaming industry needs. We celebrate Hideo Kojima’s work because it isn’t the norm. We salivate over Death Stranding trailers because we have no idea what’s happening in them, unlike other blockbusters, where potato-shaped men clutch guns the size of toddlers and blow up meaty aliens.

Usaya Co., the developers of My Horse Prince, may not be operating at the same auteur level as Kojima, but their weirdness is no less necessary. As I tapped my way through a slog of samey levels, all I could think about was how different it was from the majority of games I played this year. It isn’t focused on being fun or touching or humanizing. From a cynical standpoint, it’s focused on showing you advertisements. From a more generous view, it’s focused on being delightfully, unapologetically strange.

It’s committed to weirdness. Each chapter ups the ante with a new challenge to be overcome, something that seems impossible when you start out with such a bizarre premise. I like that. I want to be challenged. I want to be pushed out of my comfort zone. I love having no idea what will happen next in the story because my expectations are tied into conventional game storytelling, not a conscious desire to push on what weird can really mean.

Not all games will benefit from prioritizing strangeness in their narratives or gameplay, but challenging the common conceits for what games can do doesn’t always mean a new mechanic or an intriguing protagonist. Sometimes it’s throwing convention and practicality out the window and just reveling in making us screw up our faces and demand that our friends take a look at what we’re playing. It’s brilliant from a marketing standpoint, and intriguing from an artistic one. Even if this example fails to captivate, I want to see more games diving deep into the bizarre rather than dipping in their toes.

My Horse Prince isn’t anywhere near the best game I played of the year. In fact, it might be one of the worst, but that’s only when looking at it as a game and its relationship to other games. On its own, divorced from superior visual novels and dating sims like Hatoful Boyfriend and Rose of Winter, it is something interesting and thought-provoking.

My Horse Prince isn’t anywhere near the best game I played of the year. In fact, it might be one of the worst, but that’s only when looking at it as a game and its relationship to other games. On its own, divorced from superior visual novels and dating sims like Hatoful Boyfriend and Rose of Winter, it is something interesting and thought-provoking.

I would rather have a dozen bizarre premises like My Horse Prince than another white man with a rocket launcher. I would rather date a hundred terrible horse men (because make no mistake, Yuuma is an awful boyfriend) than be faced with the same revenge story I’ve already played ten times this year. I would rather games entice me with the promise of something different as a pretense to show me Game of War: Fire Age and Target advertisements than paw at my wallet for more photorealism, more gritty revenge stories, more musings on overcoming the burden of white male mediocrity.

My Horse Prince is bad. But it’s also good. Moreover, it’s weird, and weirdness reminds us that games are capable of so much more.