Disclaimer: an entry pass for Star Wars and the Power of Costume was supplied by the museum.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably familiar with Star Wars, at least a little bit. The massive sci-fi franchise infiltrated popular culture decades ago. Just when you think you’ve seen the last of it outside of re-runs and movie nights with friends and family, it’s back, complete with hype, merchandise, and marketing stunts.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m a Star Wars fan. I grew up with it. Whether the “original” Star Wars (Episodes IV, V, and VI) or the “new” Star Wars (Episodes I, II, and III), I’ve seen them all. Multiple times. When Episode I was released, I camped out in front of the movie theater with my other geeky friends from high school so that we could score neck-bending front seats for the midnight release. And yes, my heart flip-flopped a bit and I did a little happy dance when I saw the Episode VII teaser trailer last year.

The upcoming release of The Force Awakens is of course good timing for other Star Wars themed events. One such event is a traveling museum exhibition entitled Rebel, Jedi, Princess, Queen: Star Wars and the Power of Costume, put together by the combined powers of the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, and Lucasfilm. The first stop for this exhibition? Seattle’s EMP Museum. (Luckily for me!)

Back then, it was called the Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum, aka EMP-SFM. My wife and I thought it was fantastic. We loved meandering through the multi-level, spacious galleries. Although we didn’t know it at the time, the EMP-SFM would provide her first job in Seattle. A couple of months later, she was one of those uniformed people standing in the corner and reminding visitors not to take pictures of The Terminator robot or the Alien queen. [FYI: no one from the EMP influenced this article.]

It’s because of my wife that I know the EMP has a long history with Star Wars. The creepiest thing she had to do for that job was roam the dimly lit sci-fi collection after hours to the sounds of Darth Vader’s hoarse breathing over the loudspeakers.

I unwittingly arranged my tour of Star Wars and the Power of Costume for Friday, September 4, aka #ForceFriday. (Yes, sometimes I live under a rock.) Although #ForceFriday was conceived of as a marketing ploy for the new line of Star Wars toys, it was embraced by the fandom as a chance to celebrate. As I wandered the exhibition, listening to instrumental pieces from the film scores and peering at the elaborate costumes, I felt buoyed up by the camaraderie and fan enthusiasm of those around me.

It’s a wonderfully constructed exhibition. For starters, the costumes are really cool. I mean, we’re talking about ephemera from some incredibly influential cultural phenomena! I’m as much of a fan as a critic. How awesome was it to see the Han Solo outfit worn by Harrison Ford? Chewbacca’s fur suit? Darth Vader’s imposing black garb? Leia’s infamous bikini right next to her badass Boushh disguise? SO AWESOME.

Fanthusiasm aside, these costumes are wonderful examples of their craft. Particularly the costumes from Episodes I, II, and III (it was obvious that they had a much more, ah, roomy budget). Costume designer Trisha Biggar’s care and talent is readily apparent: details are exquisite, stitches precise, colors vivid, and fabrics glorious. They’re beautiful, beautiful objects in and of themselves, even extracted from the context of the characters and the films.

The exhibition is lovely. The backdrops are watercolor landscapes that set the scene for the costumes without being overwhelming. Costumes are grouped to suggest action: Jedis spar, senators converse, Queen Amidala’s attendants trail behind her. It’s easy to imagine the characters within the clothes.

Take, for instance, one of (Queen) Padmé Amidala’s many, many costumes. Her wedding gown is displayed on a mannequin that stands facing an Anakin mannequin (yes, I really wanted to write that), reflecting the scene from Episode II: Attack of the Clones in which the gown featured. I stared at the details on that dress for at least five minutes. As I discovered, it was crafted from an antique Italian bedspread, and Trisha Biggar stayed up late on the night before the shoot to add final details and flourishes. If she hadn’t, would those details have been missed by the audience? My guess is: probably not. But the fact that Biggar went to that length goes to show her commitment to her craft. Also, likely, that details make the scene and the character, whether or not the audience is consciously aware of it.

Let’s look at a few of Padme’s other costumes, too. Her “Meadow Picnic Dress,” used in the scene where she and Anakin get romantic out in the countryside, is all storybook Medieval princess: flowing silk, pastel ribbons, and delicate filigree over a stiff bodice with bare shoulders. The famous “Throne Room Gown” is stunningly bright and unreservedly royal: deep crimson, shining gold embroidery, rich faux fur lining. And, actually, it’s much smaller than its imposing presence suggests. Later in her life, Padme wears lush velvet robes that mark her as a senator. The long sleeves, tight corset, and caged hair reminded me of Elizabethan women of state.

But oh, as much as I loved the exhibition, there was a great big elephant in the room, and it was trumpeting one thing: cultural appropriation.

I am not the first to point this out. I’m not going to be the last, either. It’s a known problem. Star Wars character design flat out crosses into racism more than once.

Now, the exhibition did a great job tracing the cultural influences behind some of the costume designs, and it’s fascinating. I was an art history major; I’m constantly intrigued by cultural exchange through the medium of art, and I love connecting the dots of artistic influence across time periods and continents. And that’s precisely the lens through which the curator presented the costumes of Star Wars: a solidly academic, art historical lens.

And in this context, that’s problematic.

A photo posted by SITES Exhibitions (@sitesexhibitions) on Feb 24, 2015 at 6:45am PST

Back in July, the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (@sitesExhibits) hosted an “Ask the Curator” Twitter chat with the curator of The Power of Costume, Laela French. It was fun! The questions were great, and it was cool to learn that Chewie’s fur needs to be groomed with fingers and wide-toothed combs. Then I asked this, and they replied:

“The costumes pull from cultural iconography so we can readily identify that character’s role in the movie.” That’s very factual. The exhibition pointed out, for instance, the ways in which the costumes and character designs of the Star Wars villains echo the regalia of the Axis powers from World War II. Darth Vader’s design draws on Japanese samurai armor: the helmet has those flared edges, the shoulders are broad, and Vader’s suit electronics suggest the shape of a chest plate. (See the Instagram photo below of one of the exhibition’s didactics for a direct source.) Also, consider the uniforms the Imperial officers wear. These are modeled off Nazi uniforms: starched cloth, broad belts, belled legs, equestrian style tall boots. George Lucas, mastermind behind the films, didn’t want viewers to make that connection overtly, but he clearly wanted to bring the association of militaristic, hubristic power.

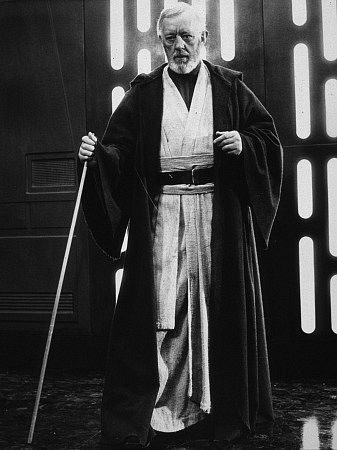

On the flip side, the Jedi costumes also draw from samurai garb. Take Obi-Wan Kenobi, first portrayed by Alec Guinness and later by Ewan McGregor. Note the robe with a wide collar and wide, obi-like belt. (Is his name really a coincidence? Really?) Now, see this still from Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 film Seven Samurai: Clearly similar, right? Let’s extrapolate this out a bit. Jedis are versions of samurai warriors: they have a strict code of honor, they’re trained in a master-student system, they wield long, thin, deadly swords. Darth Vader used to be a Jedi until he went over to the dark side of the Force, at which time he became an evil samurai and donned the scary armor. So in one fell swoop, Lucas has evoked romanticized and fearful notions of the Japanese people—both of which have the potential to be “othering.”

What’s missing from the exhibition is even an acknowledgement that cultural appropriation, as opposed to cultural appreciation, is when a dominant culture co-opts aspects of a dominated culture. What’s wrong with that, you ask? Please, read this article.

To expand upon the curator’s response to my Twitter question: using existing cultural designs not only gives the “fictional creations a realistic foundation” (Doug Chiang, Design Director for Episode I, II quote seen above), but it’s also visual shorthand for the viewers. In other words, the films give their characters greater depth by taking advantage of viewers’ preconceptions. Think of Queen Amidala’s costumes, discussed above. Depending on what she’s wearing, Padme is alternately “stately” (Elizabethan influence), “innocent” (Medieval European influence), or “exotic” (Mongolian or Chinese influence). It’s that “exotic” bit that’s particularly problematic. Think about it: Star Wars puts a white woman in the garb of a Mongolian princess in order to make her seem exotic, which is also coded as desirable, a.k.a. Orientalism. Here, listen to George Lucas himself say “exotic” multiple times.

A photo posted by Dara Turransky (@7luckydogs) on Apr 13, 2015 at 8:03pm PDT

The thing is, the exhibition tackled Leia’s slave outfit head on. Yes, the outfit that inspired some controversy over the summer when “Slave Leia” toys hit the shelves. According to the didactics, Leia turns the whole thing about being an “object” (that is, visual object for the male gaze) on its head by using her outfit as the means for revenge against her captor, Jabba the Hutt. In case you’ve not seen this scene, Leia uses her chains to choke that big green toad to death. I’m not arguing that that isn’t freakin’ awesome, and of course I always cheer when Leia wins her freedom and gets to ditch that metal bikini.

If the exhibition addresses one “politically correct” issue, why does it dodge discussions of race and cultural appropriation?

Well, you may be wondering what my point is. Am I asking that this exhibition disappear? Should it have never happened to begin with? No, I don’t think so. Star Wars is here to stay, as problematic as aspects of it are. What I am asking for is acknowledgement of its problems.

Let’s appreciate the costumes for what they are: beautiful art pieces and the end result of a lot of hard work by talented individuals. Let’s not gloss over the fact that they’re also examples of how the American movie industry perpetuates harmful cultural appropriation. There’s a learning opportunity here that has been sadly passed by. (I know, I know. Lucasfilm is a co-sponsor of the exhibition. It’s not likely the company would agree to a critique of itself. Still.)

Don’t want to take my word for it? The EMP exhibition closed on October 4, but The Power of Costume opens again in New York City in November and will be touring through 2019. Go! By all means, enjoy the artistry and the fandom; I definitely did. But keep in mind that there are potentially harmful ramifications from the cultural shorthand the costumes use to augment the characters.