In part one of this tangle, I talked about four ways I conceive of the relationship between comics and religion: comics as religion, comics in religion, religion in comics, and religion and comics in dialogue. In this month’s installation, I’ll give you second two categories (religion in comics and religion and comics in dialogue)—but be sure to back up and check out the way I introduce the whole thing in part one of this essay. (Bonus, I hint at my awkwardness at cocktail parties.

These categories are modeled on the four relationships between religion and popular culture more broadly as outlined in by Bruce David Forbes in his introduction to this great popular culture book with Jeffrey Mahan. The relationship is still tangled, but at least these categories help us sort out what we are talking about.

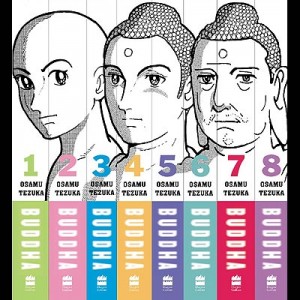

The category religion in comics encompasses comics that contain different expressions of religion. These first include comics that focus explicitly on religion and religious figures in a religious context such as Osamu Tezuka’s eight-volume series Buddha, an imaginative retelling of the entire life of Siddhartha, the foundational figure of Buddhism. The work acknowledges the religious context of Buddha without portraying the Buddha in a necessarily traditional way.

The category religion in comics encompasses comics that contain different expressions of religion. These first include comics that focus explicitly on religion and religious figures in a religious context such as Osamu Tezuka’s eight-volume series Buddha, an imaginative retelling of the entire life of Siddhartha, the foundational figure of Buddhism. The work acknowledges the religious context of Buddha without portraying the Buddha in a necessarily traditional way.

Second, there are comics that contain explicitly religious figures without focusing on their religious significance per se. This especially happens when religious figures are used for their unique stories rather than to offer a religious message. For example, the character of Thor in Marvel comics is a “god” in the comics, but the nature of his actual religious significance for German neo-pagan or different modern groups that practice modern Heathenry is hardly touched over the decades-long run. There’s been some awkward stuff recently in the Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D show that vaguely acknowledges contemporary religious groups, but that’s really a story for another time. Recently, the overdramatic guff over Thor’s powers going to a woman have made even more clear to even the casual fan that “Thor” in comics is a title and has only superficial things in common with his namesake. Thor controls thunder and certainly has human qualities, but hardly ever becomes a woman. (That’s Loki.)

Second, there are comics that contain explicitly religious figures without focusing on their religious significance per se. This especially happens when religious figures are used for their unique stories rather than to offer a religious message. For example, the character of Thor in Marvel comics is a “god” in the comics, but the nature of his actual religious significance for German neo-pagan or different modern groups that practice modern Heathenry is hardly touched over the decades-long run. There’s been some awkward stuff recently in the Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D show that vaguely acknowledges contemporary religious groups, but that’s really a story for another time. Recently, the overdramatic guff over Thor’s powers going to a woman have made even more clear to even the casual fan that “Thor” in comics is a title and has only superficial things in common with his namesake. Thor controls thunder and certainly has human qualities, but hardly ever becomes a woman. (That’s Loki.)

Above: Loki’s done this before.

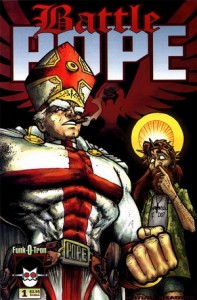

In putting religion in their comics, some comic artists do a kind of act of what philosopher Gerard Genette calls, “transvaluation”—taking characters down from their religious pedestals and giving them human qualities. For example, Jesus in the series Battle Pope is nothing more than the ne’er-do-well sidekick for the divinely super-powered, corrupt and lecherous pontiff.

In putting religion in their comics, some comic artists do a kind of act of what philosopher Gerard Genette calls, “transvaluation”—taking characters down from their religious pedestals and giving them human qualities. For example, Jesus in the series Battle Pope is nothing more than the ne’er-do-well sidekick for the divinely super-powered, corrupt and lecherous pontiff.

Yes, that’s Jesus picking his nose.

Battle Pope, by the way, is the brainchild of Robert Kirkman, now-famous creator of The Walking Dead. (Pick up his early stuff so you can say you knew him when.) Kirkman is hardly alone in the practice of transvaluation. Comic Book Religion, a site devoted to tracking the religious affiliations of characters in comics, has identified 166 distinct comic book appearances of Jesus Christ to date across multiple publishers and titles. Some of these are complimentary, but many are anything but! Reactions to the transvaluation of deities and important religious figures are, of course, mixed. Some people love seeing their own (or, more disturbingly, other people’s) religious figures mocked. Of course, it’s not always easy or possible to go along with the joke when it’s on you.

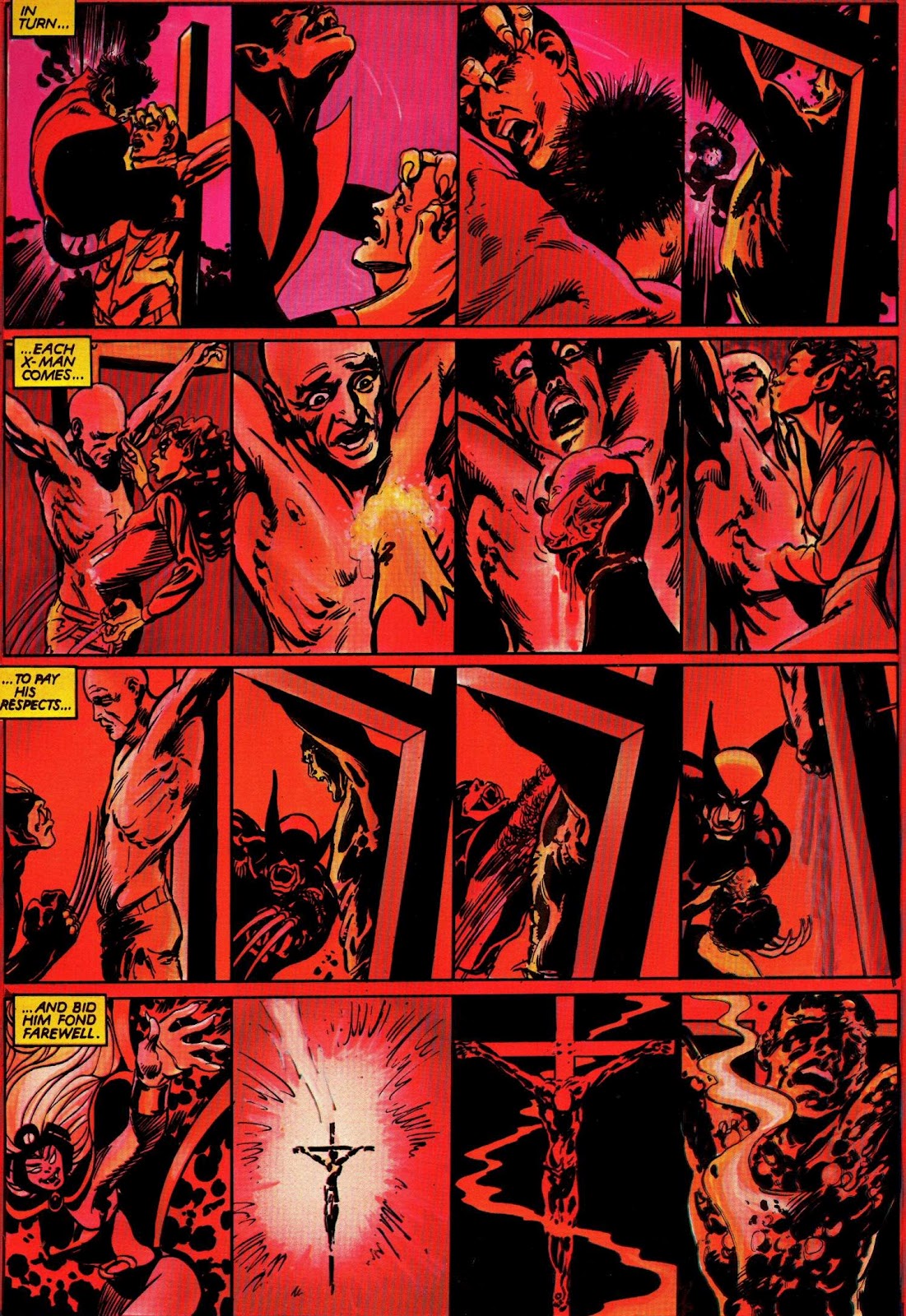

Comics also contain implicit references to religion. The most obvious and pervasive religious theme in superhero comics is a Christian trope—the “Christ figure.” That is, stories that use other characters, events, or images that recall or resemble the story of Jesus. Usually, they focus on the bit of the story where Jesus sacrifices himself to save everyone. Very few Christ figure superhero stories seem to focus on feeding people or fishing. Just not as flashy, I suppose, as something like the sacrificial Death of Superman. The interest in the phenomenon of Christ in spandex is widespread. Many scholars (including these, these and these) productively mine these works for their religious themes — whether the creators necessarily anticipated them or not.

Some comics that use Christ themes are obvious about what they are referring to, but don’t necessarily use them in ways the average reader might expect. In 1983, Chris Claremont and Brent Anderson created the classic X-men graphic novel called God Loves, Man Kills that connected the way a church-led organization crucifies the white male leader of the mutant X-men, Charles Xavier, and lynches two African American children. The fact that the children are also mutants does not blunt the political message or the emotional impact of the scene at all. There is no question that Claremont wishes the reader to recall Jesus and connect his suffering to both the children and Xavier; his caption at the start of the illustration of Xavier’s crucifixion is “And they bring him unto the place Golgotha… and they crucify him.” It’s an obvious quote of King James Bible rhetoric.

The position of religion here is ambiguous; the villain is a Christian leader, but the solution to the X-men’s problem ends up being religiously inspired as well. This is a moment when religion in comics begins to be religion and comics in dialogue.

Comics and religion cannot seem to stay away from each other. Because many comics are part of subculture, they get away with questioning powerful religious mores and figures in a way that films with their large budgets and political studios simply cannot afford to do. Of course, this has not been without consequences. The United States comics industry in particular has long suffered for its edgier elements. Often, loud voices of dissent about comics come from religious communities. This struggle is well documented in the book The Ten-Cent Plague. But, relative freedom of expression presents the opportunity for religion and comics to enter into dialogue.

Good Dialogue hardly ever involves burning things, unless we’re making s’mores and not using someone’s creative work as kindling.

This back-and-forth is not always respectful on either side, but the conflict is fascinating theatre. Religion can enter comics in a scandalous way—inspiring religious ire, pillorying mainstream religious mores or simply putting a twist on religious figures that are already established in the mainstream mind. This dialogue sometimes suffers from a deafening silence from both comics creators and religious people. While an offbeat retelling of a gospel comic like Markedenjoys the publication and marketing of a religion-affiliated press, the original story ofAmerican Jesus (or Chosen, depending on your version) languishes with only one volume completed. (Tell me more, Mark Millar, for the love of Pete.) Unfortunately, many religious people hardly touch the comics that directly transvalue their religious figures. They simply ignore them. It’s a pity! I think a conversation between creators of these comics and religious people who can stop to listen would be thought-provoking for both sides.

Comics creators are eager to dip into the already highly-charged conversation that religious subjects offer. Publishers are desperate for the new mediums that they can sell to new markets. They’ve finally discovered that women read their comics (and even write about them), now I submit that the vast number of people on the planet whose lives are somehow entangled with religion would love to read about these ideas in new, creative ways.

Want to read more about the glorious tangle of comics and religion? The wonderful academics and comics-people over at Sacred and Sequential are in the process of putting together a whole organization to talk this over and keep people informed. Full disclosure: I am a member of their site and huge fan of their cause—educating people about religion and comics. If you want to read more about comics and religion, they have started a bibliography that you should check out. For the moment, it’s things holy and superheroic (gods in capes, spandex and Clark Kent disguises for a few examples), but it’s an expanding list. They tweet at @religioncomics, and you could follow me or tweet at me @ecoody, if that sort of thing appeals to you.