“Animation is for weirdos.”

—Petra Freeman

During the eighties and nineties, Channel 4’s patronage of experimental animation provided opportunities for new talent across the country. Some of these animators arrived at the medium very much through the back door, bringing with them aesthetic sensibilities unlike those of anyone else in the field. One such person is Petra Freeman.

During the eighties and nineties, Channel 4’s patronage of experimental animation provided opportunities for new talent across the country. Some of these animators arrived at the medium very much through the back door, bringing with them aesthetic sensibilities unlike those of anyone else in the field. One such person is Petra Freeman.

As Clare Kitson relates in her book British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor, Freeman had little interest in animation as a child. Nor was she initially keen to study the medium: her chosen subject at the Royal College of Art was illustration. Noticing that her art showed a narrative bent, however, her tutor nudged her towards the college’s animation department. As Freeman’s favoured technique involved making drawings on glass using soot, department head Richard Taylor introduced her to paint-on-glass animation. This technique was already established–North American animator Caroline Leaf being its best-known practitioner in the English-speaking world–but never achieved acceptance within mainstream animation, being better suited to individual work.

Freeman found that animation suited her needs entirely. “Because of the slowness of animation, it gives me a long time to think about what it is I’m really trying to say,” she commented in an interview. “It’s a perfect medium for me to get my ideas across, rather than trying to put everything into one static painting.” The paint-on-glass process proved particularly appealing to her, for the very reasons that other practitioners might find off-putting:

“I think painting on glass wouldn’t suit a lot of people because there isn’t very much planning concerned, because you go in on a day, and you have to paint it there and then on a sheet of glass which is back-lit. I tend to go to a café in the morning and think about what I want to do, and then I come home and then you just draw it freehand, and you change the drawing freehand, and it tends to evolve into the next look of something, where you make a character move across the scene. But there is no planning: you can’t trace it or anything, you have to just draw it quite instantaneously. So that’s always kept it fresh and interesting for me, because I’m not quite sure how it’s going to go.

The fluid nature and the slowness of it means that my mind can wander while I’m doing it, it’s kind of a concentration, but also it gives you a chance to think about how you might want to plan the next scene, or you kind of get seduced by the look of a particular image.”

Freeman completed her graduation film Felt, Lifted and Weighed in 1990. The short uses what would later become her characteristic style, albeit in a more basic form than in her subsequent work. The protagonist is a little girl who occupies a plain white backdrop alongside an object that repeatedly metamorphoses: it starts out as a mirror, before becoming a spinning wheel, a chair, and a bed, amongst other things. Strange beings periodically emerge from this shape-shifting; some are distorted animals, while others are nondescript mixtures of human and object.

The film is often unsettling. This is partly due to its use of sound–the eerie whistle of blowing wind plays through much of it, while other noises are used as abrupt punctuation–and also because of Freeman’s weird, ambiguous imagery. At one point, the girl is surrounded by a ring of triangular figures with long, clawed arms, halfway between anthropomorphised trees and hooded cultists; they reach out and tear off her clothes. At the same time, however, the girl shows a degree of control over this nightmarish imagery, as when she apparently causes the triangular creatures to burn away to nothing.

At the time Freeman graduated, Channel 4 and London’s Museum of the Moving Image were running a scheme called Animator in Residence. The idea behind this project would be that new animation graduates would be given funding to make short films and in return act as living exhibits in the museum, by producing their initial rushes in a booth viewable by attendees. Working with fume-heavy oil paints in a glass box for three months was not always a comfortable experience, but the resulting test footage impressed Channel 4 enough for Freeman’s film–titled The Mill–to be put into production.

Its loose narrative focusing on a lost child’s search for companionship, The Mill works with similar imagery to Felt, Lifted and Weighed, once again showing a little girl and an array of shape-changing objects. Certain specific images can be found in both shorts, such as the spinning wheel, which is shown bizarrely jutting from a cloud in the sky. “I’m quite compulsive in what I draw,” says Freeman. “I tend to repeat the same image over and over again.”

But Freeman’s technique is more refined than in her student film. The Mill shows a better balance between the consistent and the amorphous. Evocative landscapes of fields, trees, and dark-clouded skies form from the shifting paint, before playing host to surreal transformations. Faces and hands periodically appear on previously inanimate objects, ready to act as guides for the girl, only to guide her right into another bewildering situation. The girl encounters a dreamlike distortion of space as he makes her way through her shifting environment.

Many of The Mill’s seemingly random images were lifted from Freeman’s childhood memories. She grew up in a Cornish village near a string of mills, hence the film’s imposing structures and spinning wheel. Her father was a beekeeper, which informs the recurring motif of bees. The character of a beekeeper appears at one point and serves as the only adult figure of reassurance before departing. A swarm of bees repeatedly interacts with the girl, and finally, a bee-human hybrid appears–a sort of dark fairy–which becomes a playmate to the girl as the film closes.

The short was complemented by the music of Sofia Gubaidulina, a Russian musician whom Freeman discovered while visiting a concert during a break from the animation process. The Mill aired on Channel 4 in July 1992, as part of the Secret Passions series which ran animated shorts alongside behind-the-scenes material, and won the debut prize at the 1992 Hiroshima International Animation Festival.

Freeman’s next film, Jumping Joan, was completed in 1994. This was funded by Animate!, a scheme set up by Channel 4 and the Arts Council of England as a means of financing arthouse animation. Like The Mill, Jumping Joan–the title of which comes from a nursery rhyme about a lonely child–depicts a little girl who exists in a largely natural environment, encounters various indistinct and amorphous beings, and eventually gains a degree of control over her shape-changing milieu. Giants emerge from the earth and sky, acting in a protective, quasi-parental manner. Smaller silhouetted figures also turn up, apparently created by the girl herself, and act as friends or perhaps pets. These resemble the bee-child in The Mill, although the two with rabbit-like ears also recall the nondescript animals in Felt, Lifted and Weighed.

But despite making use of such otherworldly imagery, Jumping Joan is, on the whole, a more naturalistic film than The Mill. Freeman’s character animation is more refined, with the girl’s smaller movements–brushing her hair from her face, skipping as she walks–being convincingly lifelike. The film shows a sharper eye for finding the fantastic in the everyday: translucent curtains billow like ghosts, while the girl plays with her enormous shadow as it appears on the wall of her house, prefiguring the silhouette-creatures that she later creates.

In a first for Petra Freeman’s films, the little girl protagonist is not the only child to appear. One scene involves a pair of kids who seem to exist outside of Joan’s fantasy world, and perhaps even violate it: they hold up one of her silhouette friends, now a lifeless humanoid shape, and poke it with a stick. Joan approaches them and, startled, they run away.

Much of Petra Freeman’s subsequent projects have involved working with children alongside her partner Tim Rolt at Bath-based Rapid Eye Movies. Resulting films include the Tales from Columbia shorts–“Nobody Returns” and “Mission Possible”–in which the pupils of the Columbia Road Primary School in London send up various genres from zombie films to game shows. But with her 2005 short Bee Boy, Freeman was able to return to the imagery of her earlier films while working in live action.

At the start of the film, a little girl–who, in clothes and hair, closely resembles Freeman’s animated heroines–plays with toys and found objects in a garden shed. In the kind of spatial distortion turns up throughout Freeman’s work, the shed contains a doorway that somehow leads to a small clearing in a wood; here, the girl comes across a stuffed replica of the bee-child from The Mill. Accompanying her are two toy bunnies, animated in stop motion, which echo the two rabbit-like figures in Jumping Joan. An oddly-proportioned beekeeper–another image from The Mill–appears and tugs the bee boy from the girl’s arms before storming away. The girl follows and finds the bee boy being forced to operate a strange machine; once again, Freeman appears to be recalling the mills from her childhood. The girl rescues him and takes him back home.

While she was willing to branch out into live action and stop-motion, Freeman has shown little interest in computer animation:

“I think it’s very important for me to handle materials, I don’t find it satisfactory just to work with a computer. There has to be a handling of the materials and a sensation of the smell of what I’m working on and the texture, and to use implements to arrive at a particular image, it has to be like that with anything–if it was print-making, painting, sewing, any of those things. I suppose it’s a link to a kind of compulsion, where I have to be making something all the time.”

At around this time, Freeman was returning to the medium that first led her to animation in her student days: narrative illustration. British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor, published in 2005, reported that Freeman was working on “a children’s book; dark, mysterious, and with illustrations which cry out to be brought to life in animation…” This comment, it turns out, was an accurate prediction of how the project ended up.

“I was making books where one page turned over, and the image led into the next image with cut-throughs, trying to get away from film-making,” Freeman later explained. “But when my friends saw it they just said ‘well, that’d make a really good film,’ so I made it into a storyboard!” And so, Petra Freeman made her return to paint-on-glass animation with Tad’s Nest, a 2010 short backed by Animate Projects, the latest incarnation of the Animate! scheme which had previously funded Jumping Joan. Once again, she drew upon her childhood in a Cornish coastal village for inspiration.

“Tad’s Nest was somewhere that I’d always heard the grown-ups talking about,” she relates. “I didn’t really think about what the words meant until I asked an old man who used to live at the end of our drive.”

“’Tad’ is a word for an eel, and Tad’s Nest was a place a little upstream along the north Cornish coast where the young eels come up to grow into adults before they return to the sea I could have been playing in Tad’s Nest any time.”

“It was very overgrown,” she adds. “Not many people bothered to go down there. It was covered in brambles, it was only if you bothered to scrabble about in the undergrowth you’d get down there.”

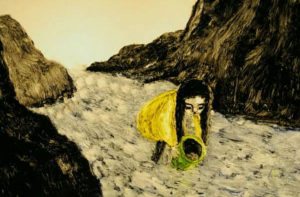

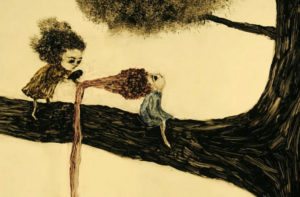

Tad’s Nest opens with a little girl, similar to Freeman’s earlier protagonists, playing in a river. However, the main character turns out to be a tiny, fair-haired child of indistinct gender, whose small stature is–due to a trick of perspective at the start–not apparent until later in the short. The child encounters a community of little, leaf-haired people who live in a tree, before running afoul of a malevolent giant.

The fantasy creatures and general ambiance of Tad’s Nest are much closer to conventional fairy tale imagery than those of Freeman’s earlier animated shorts, although she still finds room to include some idiosyncratic touches. The main character travels from place to place by splitting into component parts, which wriggle through the water like eels, another example of the dreamlike spatial transitions that clearly fascinate Freeman. The human-eating giant, meanwhile, is another weird blend of person, animal, and vegetable, catching its prey with tentacle fingers that simultaneously suggest plant stems, sea anemones, and the tongues of chameleons.

In 2012, Petra Freeman and Tim Rolt worked on a number of collaborative projects with schoolchildren as part of the Iluminate Bath event, which took place in 2012. The Important Message One, The Important Message Two, and Let the Games Commence are very simple shorts tying in with the London Olympics, which mix live action with a few spots of stop-motion; the interactive art installation “Heads, Bodies, Legs,” meanwhile, showcased children’s drawings of monsters. Illuminate Bath took place a second time in 2015, and Freeman and Rolt teamed up with local kids once again; this time, the result was a short called Flat Georgians, which was projected onto Pultney Bridge.

But it is her sumptuous paint-on-glass films that remain Petra Freeman’s masterpieces. And these works took on a new level of meaning for her when she made a personal discovery: that she has synaesthesia. “It doesn’t feel like a big deal when you have synaesthesia,” she observes, “because you just think everyone else must see things in the same way, and that people have this heightened sense of touch and sound and image linked to each other–I thought that was just the way the world was.”

Even though she was unaware of it at the time, Freeman’s animated films were influenced by her condition. “It’s interesting for me looking at old work and seeing how, without even knowing I had synaesthesia, how important that has been for me.” Indeed, she acknowledges that synaesthesia may have pushed her towards artistic expression in the first place. “It can make you feel quite isolated,” she says, mentioning a “need to express myself in a particular way, whether visually or through sound” as a child. “Animation seems like a perfect way of doing it.”

“I would like to do some work directly about having synaesthesia, I would find that very interesting.”