Melinda Beasi talks girls comics, blogging, and international manga fandom.

Melinda Beasi is founding editor of Manga Bookshelf, a manga review site home to a wealth of reviewers with their own tastes and subjects… including our own founding editor here at WWAC. Since interviewing your own boss is a bit of a funny one I took my chance: this is the first of several interviews by me, Claire. Hello!

But back to Melinda. You can check out her impressive resume – including stints at Comic Book Resources and PopCultureShock – here and you can find her writing updates on Twitter. She’s from Massachusetts, which is in the USA. She will make you want to read Nana.

But who needs a long introduction? Get to the answers!

We talk internationality, “girls’ comics,” large-scale conversation, and how it pays to be personal.

What makes it manga for you? Above any other flavour or culture of sequential art.

This is a tricky question, only because an argument could be made that I’ve never really given other comics (or western comics, at least) a fair chance. The truth is, aside from some long-beloved newspaper comics, the first comic to ever truly capture my attention happened to be manga (Yumi Hotta & Takeshi Obata’s 23-volume shounen series Hikaru no Go), a startling event that occurred just months after a dramatic LiveJournal entry in which I loudly announced that I could never love comics. Reading Hikaru no Go led me to more and more manga (and later, manhwa), but it’s possible that my preference for comics from Japan could be chalked up to little more than exposure. Having said that, there are a few characteristics common to manga that I haven’t found in the admittedly limited number of western comics I’ve personally encountered.

This is a tricky question, only because an argument could be made that I’ve never really given other comics (or western comics, at least) a fair chance. The truth is, aside from some long-beloved newspaper comics, the first comic to ever truly capture my attention happened to be manga (Yumi Hotta & Takeshi Obata’s 23-volume shounen series Hikaru no Go), a startling event that occurred just months after a dramatic LiveJournal entry in which I loudly announced that I could never love comics. Reading Hikaru no Go led me to more and more manga (and later, manhwa), but it’s possible that my preference for comics from Japan could be chalked up to little more than exposure. Having said that, there are a few characteristics common to manga that I haven’t found in the admittedly limited number of western comics I’ve personally encountered.

Though manga is an incredibly diverse medium, it is for the most part character-driven, long-form storytelling, with each series produced in its entirety by a single creator or team. Artwork and dialogue do most of the heavy lifting, with very limited use of narration, embodying the principal of “show, don’t tell” better than nearly any other type of storytelling on paper I’ve seen. My good friend Robin Brenner has often said that she perceives more similarity between manga and her favorite television dramas than she does between manga and other comics, and I’d probably agree. Also, the manga industry offers up a wealth of talented and successful female artists, writing across multiple genres and demographics, which tends to satisfy my tastes in particular.

Take, for example, Hiromu Arakawa’s shounen epic, Fullmetal Alchemist, which was incredibly popular with manga fans in Japan and here in the west. It’s an epic fantasy series, twenty-seven volumes long, written and drawn in its entirety by a single (female) creator. It’s meticulously plotted from start to finish with a clear beginning, middle, and end, and it manages to be both intensely character-driven and action-packed at the same time. Though it was published in Square Enix’s Monthly Shonen Gangan, which is aimed at elementary school and teen-aged boys, it is filled with awesome female characters (in appropriately practical clothing) and addresses topics like religion, ethnic genocide, and the nature of humanity, alongside standard shounen themes like loyalty and friendship.

And that’s just manga for young boys. Once you start exploring what’s out there for girls and adults, the range is pretty astonishing.

On a side note, when it comes specifically to girls’ comics, I probably like sunjeong manhwa just as much as (and occasionally more than) shoujo manga. Manhwa heroines as a whole are, frankly, pretty kick-ass. The same concept applies to Korean BL (boys’ love), at least in terms of what we’ve seen translated into English, which is admittedly little compared to what we’ve seen from Japan.

Also, I’m interested in the whys of using the birth-culture signifiers for sequential art; “comics”, “manga”, “manhua”, etc – is it legitimately useful, or is it just habit?

I think it’s both useful and potentially harmful to comics culture here in the west. Every culture has its own comics tradition, and certainly the nature and history of those traditions influence the comics they produce. So on one hand, these labels can serve as a useful shorthand for readers in terms of what they can expect from any particular comic. When I’m in a bookstore or comic shop, I like to be able to go over to the manga section, because I know I’ll be able to find the kind of stories I’m looking for in a format I’m comfortable with. On the other hand, these same expectations can be grossly inaccurate and really polarizing among comics fans, and I have wondered if they do more harm than good.

So I guess I think it’s a bit of both.

Can you tell us a bit about how you started out blogging and grew the site to the size it is today?

Sure! Honestly, I find the whole thing a little bewildering. I started blogging on Diaryland back in 2001, and followed my friends to LiveJournal a couple of years later. I’d never successfully kept a paper journal, even as a teenager, so I never believed it was something I’d keep up with. I was really unprepared for the vibrant fandom community on LiveJournal, and what it would bring out of me over the next several years. To a huge degree, I learned to blog on LiveJournal. That’s where I learned to write, not just for myself or my close friends and family, but for an audience with very specific needs and expectations.

In the summer of 2007, a friend finally convinced me to read Hikaru no Go, and my fandom universe was turned upside-down. When it became clear that my new fannish obsession was not even remotely interesting to the majority of my existing friends list, I started a little self-hosted WordPress blog called “There it is, Plain as Daylight” (lyrics lifted from an obscure Frank Loesser musical) as a venue for blogging about manga. I expected its readership to consist basically of my mom, and for a while that was certainly the case. Then, little by little, as I began reading and commenting at other manga blogs, my readership grew. One of my earliest readers was Michelle Smith (of Soliloquy in Blue), and I suspect she’s the one who introduced me to Brigid Alverson’s MangaBlog. One day, I was leaving a comment at MangaBlog, and accidentally double-posted. I e-mailed Brigid to apologize, and she wrote back letting me know that it was fine, and that she’d checked out my blog and found it interesting enough to add to her RSS reader. She began linking to my posts at MangaBlog, and just like that, I was part of the manga blogosphere. It was Michelle again, actually, who recommended me as a manga reviewer to then-editor Kate Dacey at PopCultureShock, which is where I really learned how to write a professional-style review. That’s also where I learned to edit (a skill still in-progress).

In 2009, after watching Brigid painfully struggle to explain the name of my blog to other journalists and publishers at the New York Anime Festival, I renamed it “Manga Bookshelf.” A year later, I asked Kate (now writing her own blog, The Manga Critic), who was struggling with an incompetent web host, if she’d be interested in joining forces. She was surprisingly agreeable. By the time we were ready to launch, we’d invited David Welsh (also surprisingly agreeable) to join us, and we launched the new multi-blog incarnation of Manga Bookshelf for the New Year. Over the next few months, we finally wore down Michelle (who was already a regular guest blogger), and invited Sean and finally, Brigid. Meanwhile, I was seeking out regular contributors to add some diversity to the main site.

Do you have core staffers/how many? What kind of behind the scenes work is necessary?

Manga Bookshelf’s six bloggers, Kate, David (currently on hiatus), Michelle, Sean, Brigid, and I are really the core of the site. We also have sixteen active contributors, some of whom maintain regular weekly or monthly columns, and a few who contribute sporadically. The site’s main bloggers are completely autonomous, at least in terms of what they publish in their own blogs (I compile and edit our group features and roundtables). We’ve been criticized for being a collection of random blogs “with no editorial oversight,” but quite frankly, the whole point there was to invite people on who are better writers than I am. That was my grand act of editorial oversight. It is an honor simply to be blogging in their presence.

Manga Bookshelf’s six bloggers, Kate, David (currently on hiatus), Michelle, Sean, Brigid, and I are really the core of the site. We also have sixteen active contributors, some of whom maintain regular weekly or monthly columns, and a few who contribute sporadically. The site’s main bloggers are completely autonomous, at least in terms of what they publish in their own blogs (I compile and edit our group features and roundtables). We’ve been criticized for being a collection of random blogs “with no editorial oversight,” but quite frankly, the whole point there was to invite people on who are better writers than I am. That was my grand act of editorial oversight. It is an honor simply to be blogging in their presence.

I am responsible for everything that is published in the main blog, however, so I do spend a lot of time editing and working with our regular contributors. It’s a great group of writers, coming to the site with varied levels of experience from university students to seasoned professionals (some far more experienced than I), so some I work with more extensively than others. A few I barely edit at all. I’m constantly learning as an editor, too, so I’m grateful for the opportunity to work with all of them, and I’m especially grateful to have been able to bring on some of my very favorite writers from my years in LJ fandom. When I decided to broaden the scope of the site, I realized that many of those women were still my favorite bloggers in any context, and I simply had to have them. I’ll admit it, I begged. And our newest contributor, Sara K., was a long-time reader, who started sending me pitches a year or so ago for various guest posts. Now she’s living in Taiwan and writing a weekly column for us about Chinese-language pop culture. She’s a dream to work with, incredibly reliable and meticulous with her work. She’s been my biggest surprise of the year.

Besides editing and scheduling posts from contributors, I also manage all the technical aspects of the site, including upgrades, troubleshooting, some coding, and design. I provide that kind of support for all the main bloggers as well, some of whom use pre-designed WordPress themes (with various levels of modification), while some I’ve designed from scratch. This can occasionally be the most time-consuming aspect of my role, though it tends to come in waves. The bigger we get, the more needs to happen behind-the-scenes. I do find that I have less and less time to write my own columns, but I think the site has benefited from the diversity of voices, so I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing.

Why’d you decide to go solo instead of working only on CBR and other sites?

I suppose I’ve just found it to be more personally rewarding. I’ve always maintained my own blog while writing for other sites, but I especially like and connect with the audience we’ve cultivated at Manga Bookshelf, and after a while I began to almost resent contributing to other sites when it seemed like our audience appreciated the work so much more. That’s probably an unfair assessment of the situation, and perhaps even outrageously inaccurate, given those sites’ vastly larger readership. But that’s really how it felt.

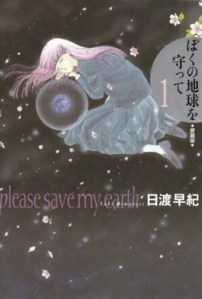

I think the real turning point for me came when Michelle and I contributed a discussion of the shoujo classic Please Save My Earth to Noah Berlatsky at The Hooded Utilitarian (where we’d contributed before). The finished post was a real labor of love, over 6500 words and carefully chosen images—the product of a solid month of work, including rereading each of the series’ 21 volumes followed by over a week’s worth of discussion, scanning, editing, and so on. The piece was largely ignored by HU’s readership, and all we could think about was how much more suited it was to our own readers. The mistake was ours, not Noah’s (he’d been very generous about accepting and supporting whatever we wanted to write about, and I’m quite grateful to him for that), but it really clarified some things for me in terms of who I was writing for.

Manga has a recent tradition of being “the girl-friendly comic genre” (linguistic problems with that description aside). Do you see that reflected and supported in publishing industry choices, translation choices, fandom mood, merchandising and so on? What could be done better?

Yes and no. Certainly there is plenty of “girl-friendly” material to read (wow, that really is a problematic description on a number of levels, isn’t it?) but it’s difficult to convince publishers to cater to adult women, despite the fact that we really do buy a lot of manga. I think the trouble is, that while female manga readers will buy books geared towards boys and men, the opposite is less often true, so the numbers aren’t ultimately in our favor. It’s hard to blame publishers for declining to publish things they know they can’t profitably sell, but those of us especially who love epic, classic shoujo and smart josei manga are much less likely to get what we want from the industry than readers who love shounen battle manga and gratuitous T&A. That’s one of the reasons I think it’s so important for bloggers like us to speak up for these titles whenever we can. We have an opportunity (however limited) to encourage readers to step outside their comfort zone, and it’s in our own best interest as fans to try to make an impact.

I’m glad you mentioned “fandom mood,” however, because unlike anime fandom (which seems to be more typically male-dominated, much like western comics fandom), manga fandom itself is a very friendly place for female readers, especially in the manga blogosphere. I can’t speak to how closely this matches manga readership as a whole, but from where I’m standing, female manga bloggers are as or more visible than male manga bloggers. I actually made a list once, though it’s terribly out of date by now, I’m sure. You’ll notice that women easily outnumber men on the Manga Bookshelf roster, and while this is undoubtedly due in some part to my own tastes, that’s been my personal experience as a fan as well. I don’t have any scientific numbers to back me up here, so this is all anecdotal, but I can at least promise that it is very easy to craft a manga fandom experience like mine, if that’s what you’re looking for.

Just to touch on the issue of merchandising, I suspect that most of what we see at conventions and so on is actually anime merchandising when you get right down to it, since that’s a much larger industry here than manga publishing. So in my mind, that’s a very separate issue. Obviously there is some crossover there, but it’s almost accidental that we see any “manga” merchandising at all in North America.

Do you think that representation and a welcoming market is enough? Do the bulk of translated and/or popular titles tend to cater to traditional gender roles, or help audiences escape those assumptions?

I don’t know if I can say that I think representation and a welcoming market is enough, but I can at least say that it’s sadly refreshing. I’m not exaggerating in the slightest when I admit that, compared to western comics and anime fandom, manga fandom feels like a real refuge. I nearly always regret it anytime I step out of the manga blogosphere and into the much larger worlds of anime or western comics fandom. For instance, I’m a regular reader of Kelly Thompson’s terrific column She Has No Head! at CBR’s Comics Should Be Good, but I’ve learned not to read the comment section unless I’m prepared to feel incensed for the rest of the day. I have such admiration for Kelly and other female writers in that world, because really, I don’t think I could handle it. My skin is much too thin.

I don’t know if I can say that I think representation and a welcoming market is enough, but I can at least say that it’s sadly refreshing. I’m not exaggerating in the slightest when I admit that, compared to western comics and anime fandom, manga fandom feels like a real refuge. I nearly always regret it anytime I step out of the manga blogosphere and into the much larger worlds of anime or western comics fandom. For instance, I’m a regular reader of Kelly Thompson’s terrific column She Has No Head! at CBR’s Comics Should Be Good, but I’ve learned not to read the comment section unless I’m prepared to feel incensed for the rest of the day. I have such admiration for Kelly and other female writers in that world, because really, I don’t think I could handle it. My skin is much too thin.

All that, of course, is addressing fandom much more than the content of the books themselves. This brings me to your second question, to which I have a fairly convoluted answer, because I think there are a large number of titles that sort of do both at the same time.

Let’s take, for example, Tite Kubo’s Bleach. This is an incredibly popular title among both teens and adults, with an even more popular anime adaptation that can be followed regularly on the Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim. It features quite a number of female characters, most of whom are warriors of some kind (this is battle manga, after all), and the ones that aren’t, are genuinely awesome, idiosyncratic, interesting women and girls with their own thoughts and lives. Furthermore, a whole bunch of them are regularly clothed from neck to toe in the same loose-fitting clothes as the men.

On the other hand, there are several female characters in the series who are so embarrassingly sexualized (Rangiku and Nell, for instance) that it’s actually difficult for a reader like me to even look at them, let alone follow their stories. And both of the series’ major story arcs (at least what we’ve seen in English) revolve around one of these generally wonderful female characters (first Rukia, and later Orihime) waiting to be rescued by Ichigo, the series’ male lead. Furthermore, if we’re talking about gender roles as a whole (not just those thrust upon women), there is no escape here whatsoever from traditional ideas about men. Many shounen manga paint a picture of the ideal male as someone who works tirelessly to build up his physical and mental strength in order to protect his loved ones, and that’s certainly Ichigo’s prime directive. Like most shounen heroes, he’s strong, stubborn, and emotionally unavailable, and those are traits the author appears to hold in high regard.

Overall, it would be difficult to make the argument that Bleach challenges traditional gender roles, and that’s certainly not an argument I’d make on its behalf. Yet, it’s still more nuanced in that area than, say, American superhero comics, which you could argue are the most similar to shounen battle manga.

I chose a shounen manga as the example here, because it’s the most popular demographic category by far, especially here in the west. Unfortunately, I can’t speak any more favorably about many popular shoujo manga, either—in fact, some of them are much, much worse. On the other hand, one of the medium’s greatest strengths is its variety. Because manga in Japan covers as much ground as, say, prose books in North America, you can nearly always find something that is exactly what you’re looking for.

What does the youth-orientation of very famous manga mean to you? I haven’t been within the manga loop recently but the heroes of the very, very western-beloved titles seem to skew younger (teenaged) than those of the popular American Superheroic series (mid-ish twenties).

I think it means a couple of things. First, it means that a lot of teens and pre-teens read manga (definitely in Japan, and on a smaller scale, here), which I think is something that can’t necessarily be said for American superhero comics. I rarely read superhero comics, and I have no expertise on the subject at all, but my understanding is that the Big Two’s target audience is adult men. Also, I think it may speak to the depth and range of teen-focused manga. I’m 43, and I still read a healthy amount of shoujo and shounen manga. In fact, when I look at this list I once made of ten favorite manga series, the vast majority of them were intended for shoujo or shounen audiences, yet they still resonate strongly with me, much like the best young adult and children’s prose fiction still does, even after all these years.

I don’t love all youth-oriented manga at my age, obviously, just as I don’t love all YA novels (even some that I loved as a teen). But there’s an enormous catalogue to choose from, even if you only count what’s been published in English.

What does it mean to find validation and joy in crossing cultures? What does it say about your country, that country, you, the art of storytelling?

Wow, that’s a big question, and I’m not sure I’m qualified to answer it, but I’ll give it my best shot.

Wow, that’s a big question, and I’m not sure I’m qualified to answer it, but I’ll give it my best shot.

I think an argument could be made that, in the simplest terms, this demonstrates the universal power of storytelling. That a middle-aged lady in western Massachusetts can feel such a strong connection to stories told by writers thousands of miles away, despite numerous cultural differences, is a pretty powerful testament to both the skill of those writers and the power of the medium they are working in.

I mention the medium specifically, here, because I think its visual nature is actually a major factor in making that connection so quickly and easily. As a reader, I don’t have to rely on my imagination alone to envision the world the artist has created, so things that might otherwise register as a cultural barrier are actually quite clear.

I am not sure what this says about either culture, except perhaps that I expect there is value for each in listening to the stories of the other. I have some pretty highfalutin’ ideas about the value of storytelling, including a deeply held belief that it is through stories that we (humans) share the most vital truths about ourselves and the universe we live in. I honestly believe that storytelling, in all its forms, is the most important thing we do as a species. So with that in mind, certainly cross-cultural storytelling can be an important tool for understanding each other.

And on a personal note (returning somewhat to your very first question), I think perhaps the reason that I so quickly felt a connection to Japanese comics in particular, is that the way in which the Japanese sequential art tradition developed (its methods of serialization, its aesthetics, its artistic ideals, its editorial process) just happens to lend itself to producing the kinds of stories I most enjoy. That is to say, I don’t think sequential art is necessarily the universal key to global understanding. It just happens to work especially well for me in this case.

Where do the bulk of your readers live (based on google analytics, etc)? Are you aware of a Japanese readership? Or Korean for your manhwa reviews, Chinese for Manhua, and so on.

Over 60% of Manga Bookshelf’s readership is from North America or other English-speaking countries, according to our site statistics. After that, our largest chunk of readers comes from Europe, particularly Germany, France, and the Scandinavian countries. We also see a good number of readers from Indonesia and the Philippines.

We do have some readership in Japan and South Korea (a little less in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong), though I’d say that there is some evidence that those readers—at least those from Korea and Japan—are more likely than not coming from within the comics industry, looking for feedback on their work. I suspect that manga and manhwa fans in Japan and Korea simply don’t feel the need to seek out a North American perspective on their own countries’ indigenous comics. And why would they?

What sort of feedback do you get, and does it differ noticeably from that which you get from American readers, or readers from other cultures again?

As you might expect, most of our written feedback comes from readers in English-speaking countries as well, particularly the U.S. and Canada, and the majority are regular readers who follow manga carefully and comment often (quite thoughtfully, too). We do have some European readers who comment regularly, and probably what I notice most about their comments is that they seem to be extremely knowledgeable about comics in general, and they’ve been reading them for a very long time.

We see very little feedback from East Asian readers (and the feedback we do see tend to come from North Americans living abroad). In fact, I think one lone reader from the United Arab Emirates probably leaves more feedback on the site than all of East Asia put together.

It’s probably also worth noting that the majority of our feedback comes from women. In fact, based on feedback alone, I’ve assumed that the majority of our readers are adult women, though that certainly could be a skewed perception.

Do you or how do you think that your gender affects the assumptions that audiences make about your site and your reviewing? Do you think that these assumptions are correct?

I think that depends a lot on the individual and where she/he is coming from. I think it’s pretty likely that many readers assume that I am reading and writing from a feminist (or at the very least, female-centric) viewpoint, and those people would not be wrong. This is not necessarily something I’m consciously doing, but I’ve certainly become aware of it myself over the past few years. I’ve even noticed (quite accidentally) that I seem to prefer manga written by women. In fact, that top ten list I mentioned earlier (which really is a little arbitrary, just as it claims) includes exactly two male creators, one of which is a male artist working with a female writer. Of course, this wouldn’t necessarily be an accurate assessment of the site as a whole (we have five male writers on our roster, after all), but you can be assured that I probably wouldn’t invite anyone to write for the site whose writing is hostile towards women.

On the other hand, I think there may also be a handful of folks out there who assume that a female-run site is somehow inherently fluffy and less intellectual than one dominated by men, and that would be a pretty foolish assumption. We can dish out fluff with the best of them (people like fluff), but I challenge anyone to make that claim against, say, Kate Dacey. Our core bloggers each have such different strengths and backgrounds—I’d like to think there’s something for everyone at Manga Bookshelf.

A lot of your contributors bring in personal information and reactions to the material they look at – is this an important part of your site and your own work? Is it something you feel is an important part of comics blogging – can someone’s reaction to a book be separate from the person that they are? And related to that, how responsible to you feel about putting an image of “yourself, who likes manga” into the world and the community conversation about manga and comics?

Hmmm, well let’s just call it a personal preference. The way I see it, there are a slew of manga bloggers and critics out there, all talking about the same books. What sets each of us apart is what we bring to the material as individuals. Without that, there would be no value in seeking out multiple reviews of the same comics, because we’d all have exactly the same things to say.

Hmmm, well let’s just call it a personal preference. The way I see it, there are a slew of manga bloggers and critics out there, all talking about the same books. What sets each of us apart is what we bring to the material as individuals. Without that, there would be no value in seeking out multiple reviews of the same comics, because we’d all have exactly the same things to say.

Just as it’s impossible to set purely objective criteria for evaluating works of art, it’s also impossible for any critic to completely remove him/herself from the equation. And while in a very formal review or piece of criticism, most writers will assume an air of authority and objectivity, I personally prefer to read something with a bit more transparency. In order to better understand the critique, I want to understand the person it’s coming from.

This is a preference that has evolved for me over time. For instance, I used to have a strong preference for reviews and criticism written in the third person (I think the site’s style guide might still reference this, actually), because I felt that they were less prone to arbitrary value statements made without any substance to back them up. But working with talented writers like David, Michelle, and Sean, I began to realize that this assumption was full of crap. Their personalized observations enrich their writing rather than detract from it, and as a result, I’ve come to favor reviews that offer personal reactions along with informed observation. Regular readers of the site will notice that I’ve mostly abandoned writing formal reviews in favor of roundtable-style discussion like Off the Shelf, and that’s been a deliberate choice. In fact, I rarely (if ever) write strictly in third person on my own site at this point, which is a huge departure from my style as a reviewer for PopCultureShock and Comics Should Be Good.

I’m not sure I ever thought a lot about feeling “responsible” about putting my personal image as someone who loves manga out into the world, but it may be meaningful to note that it was when I began blogging about manga that I also began blogging under my real name, instead of my longtime fandom pseudonym. Don’t get me wrong, I’m pro-pseudonym when it’s warranted (which it nearly always is, online, especially for women), but there was something about being a manga fan that made me want to own that identity a little more publicly.

I’m interested in writing and reading about manga, because I’m interested in people and how they think and feel–including the creators of these series, their characters, and the writers who discuss them. I’m really glad that you used the phrase “community conversation” because that’s what this is all about for me. And I think that has a lot to do with why I enjoy and encourage a personal take on the material we’re all discussing.

How has manga changed your life?

How has it not? Okay, that’s a bit much, perhaps, but manga has pretty dramatically changed my life, not just by giving me a wealth of new stories to love and a fantastic community to be a part of, but also by pushing me into become… almost a journalist. I don’t feel like I’ve quite earned that title yet, but it’s something I’d never considered striving for until I became part of the manga blogging community. It’s been a revelation for me, in so many ways.

Is there a difference for you, in the focus you’d have in a professional site review and what you’d put in a casual, “fanon” review?

Yes, definitely, even now that my “professional” reviews have become much more casual than they were in the beginning. I think with any kind of writing it’s important to be aware of who you’re writing for, and what can be fun about writing for a fandom audience, is that there is a lot of shorthand you can use that’s specific to that fandom. It’s a bit like writing fanfiction, really. You can assume that you and your audience share the same background with the material, which allows you to skip a lot of exposition and get right to the good stuff.

When you’re writing for a “professional” site, you’re usually writing for a broader audience, so you have to make sure that what you’re saying is accessible and relevant to whomever that might be. “Whomever that might be” can still vary from site-to-site. For instance, at Comics Should Be Good, I could assume that most of the people reading my reviews were comics fans, but that they might not have much experience with manga. At PopCultureShock, I could assume that most readers already had some interest in manga, but they might very well be clicking over from the main site, which focused heavily on things like movies and gaming.

At Manga Bookshelf, we can assume that most readers are real manga fans and largely adults, so we’re expected to provide thoughtful, well-informed reviews and discussion, with as much smart, pithy analysis as we can muster. We don’t always succeed (or, well, I don’t), but that’s what we’re shooting for. There are columns in which it’s more appropriate to indulge fannish tendencies, like some of my discussion posts with Michelle, and my personal favorite indulgence, Fanservice Friday (I really need to revive that column). Occasionally it’s nice to be able to fall back into that shorthand and just enjoy being a fan.

I am … honored to be your biggest surprise of the year.

Anyway, I hope that the readership in China/Hong Kong/Taiwan/Singapore/Malaysia increases. Now that my column is firmly established, I’ll try to promote it more in the learning-Chinese-as-a-second-language community (many members of that community live in China or Taiwan).

And I forgot to mention that I do miss your own articles, Melinda. I know you have an incredible amount of work to do, both for Manga Bookshelf and in the rest of your life, but if any of your commitments lighten up I hope you can write more articles for Manga Bookshelf again.

Why not have a loo at the manga podcast here, http://www.mangauk.com/index.php?p=kame-hame-huh

Thanks! Most interesting to me, though I’m not unbiased.