Kitty Pryde has been a favorite character for Jewish superhero fans since her inception, but Marauders #11 insults everything about her identity. Created by John Byrne and Chris Claremont in 1980, Kitty is notably one of the few Marvel characters who has been depicted as Jewish since her creation. By comparison, Ben Grimm, who was created in 1961, was only established on page as Jewish in 2002, twenty years after Kitty hit the scene. Kitty was depicted as fiercely proud of being Jewish, frequently wearing a Magen David — Star of David — necklace. Her outspoken nature about her Judaism was often a necessity, especially when X-Men comics relied on heavy Holocaust imagery in their storylines.

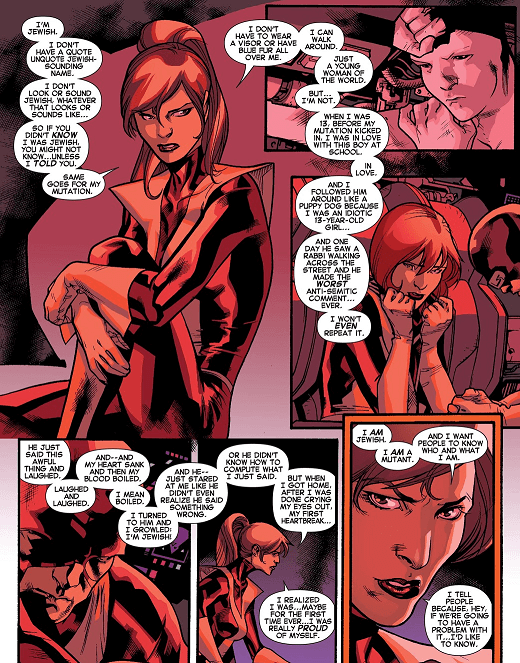

In more recent years, Marvel has become painfully ambivalent about Kitty’s Jewish heritage. Kitty is not alone in this Jewish erasure, especially not among the X-Men: Bobby Drake, who is half-Jewish, had that aspect of his identity entirely ignored in his recent solo series, and Wanda and Pietro Maximoff’s involvement in the MCU led to them being magically emancipated from their father Magneto, literally handwaving away their Jewish heritage alongside their mutant status. Kitty has suffered as an especially egregious example of this erasure. Her once curly hair is now sleek and straightened, her Magen David necklace no longer worn. Her recent ill-fated wedding towards tin-plated gentile Colossus in X-Men Gold #30 contained no hints of the Jewish traditions the character has been so vocally proud of throughout her history. With the exception of Brian Michael Bendis, who is both openly Jewish and no longer at Marvel and who notably explored the intersection between Kitty’s Jewish identity and her mutant one in All New X-Men #13, very few creators seem interested these days in characterizing Kitty as Jewish or exploring that facet of her identity.

Marauders has been an especially rough run of it for Marvel’s most prominent Jewish heroine. When the Krakoa storyline found Kitty the lone mutant unable to enter mutant paradise island through the portals that are supposed to recognize all mutants, she had to find other ways to belong. There’s a metaphor about the Jewish experience finding space among other marginalized communities in here, one which Marauders has not even attempted to touch upon because if the series has made one thing clear in its last eleven issues it’s that it has basically no interest in respectfully depicting Kitty as a Jewish character.

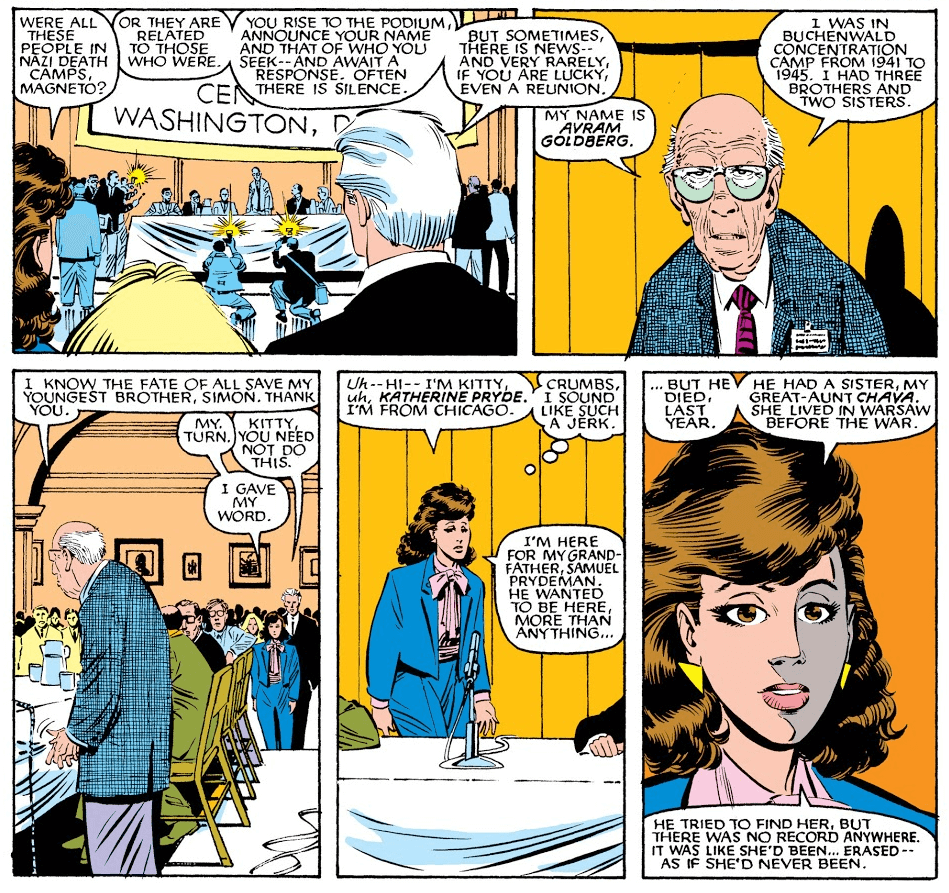

In Marauders #1, she even ditches the name Kitty in favor of Kate, a decision that left a bad taste in my mouth. What I take issue with is not the act of a character changing their name, a story that could be affirming to many, but rather Duggan’s choice of the name “Kate” in particular. While some readers wouldn’t automatically recognize Kitty as a typically “Jewish” name, many from Jewish communities would. Kate, by comparison, is a much more ambiguous moniker. The concept of toning down the ethnicity of one’s name in order to better assimilate in a new place is a sensitive one for many cultures, something touched on in All New X-Men #13 when Kitty states that she doesn’t have a “quote-unquote Jewish name.” Kitty’s surname, it should be noted, is already a shortened form of her family’s name, as Uncanny X-Men #199 notes her grandfather’s surname was originally Prydeman. There is a comparison that could be made in the act of a Jewish character arriving on an island, a gateway to a new, supposedly free world, and promptly changing her name: “We landed at Ellis Island,” quips Fran Drescher in an episode of Jewish sitcom The Nanny. “They changed our names and now we don’t know who the hell we were.”

In Marauders #2, Kate gets “Hold Fast” tattooed on her knuckles, a decision that struck me as culturally insensitive. Tattoos are considered taboo in Jewish culture, as many Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform authorities have argued that they go against religious laws, but also for what they have come to symbolize to many in a post-Holocaust Jewish society. The style and position of Kitty’s tattoos are a little too close for comfort to the numbers tattooed on the arms of concentration camp prisoners during the Holocaust, something Kitty as a Jewish person would surely be aware of well before anyone got near her hands or arms with a tattoo gun. On the very same page that mutant concentration camp survivor Bishop says that he “already has” a tattoo in reference to the M brand over his eye that marks him as a mutant — a blatant reference to the concentration camp numbers — Kitty displays no such awareness. Iceman, another Jewish mutant present in the scene, states that he will not be getting a tattoo but similarly makes no remarks on the subject of tattoos being used to mark concentration camp prisoners.

While some modern Jews have embraced tattoos, it seems strange that Kitty should remain so silent about her reasons for getting one in the same scene where Bishop references concentration camps. Marauders feels comfortable invoking fictional mutant genocide while it ignores the real genocide on which it was based. This omission seems especially glaring not only because of Kitty’s historic outspokenness about her Jewish heritage but because her great aunt Chava died in Auschwitz, as established in Uncanny X-Men #199 when Kitty spoke for her grandfather at the National Holocaust Memorial.

I believe characters should be allowed to grow and change, but I don’t think that should come at the cost of Jewish representation, and I don’t agree with the implication that removing facets of Kitty’s Jewish identity counts as upward growth for the character. Kitty’s recent appearances have been dedicated to making her look tough and cool. She can get a tattoo. She can drink in the middle of the day and kiss any man she wants. She can steer a pirate ship. She just can’t be proudly Jewish.

She’s not even allowed to be Jewish in death.

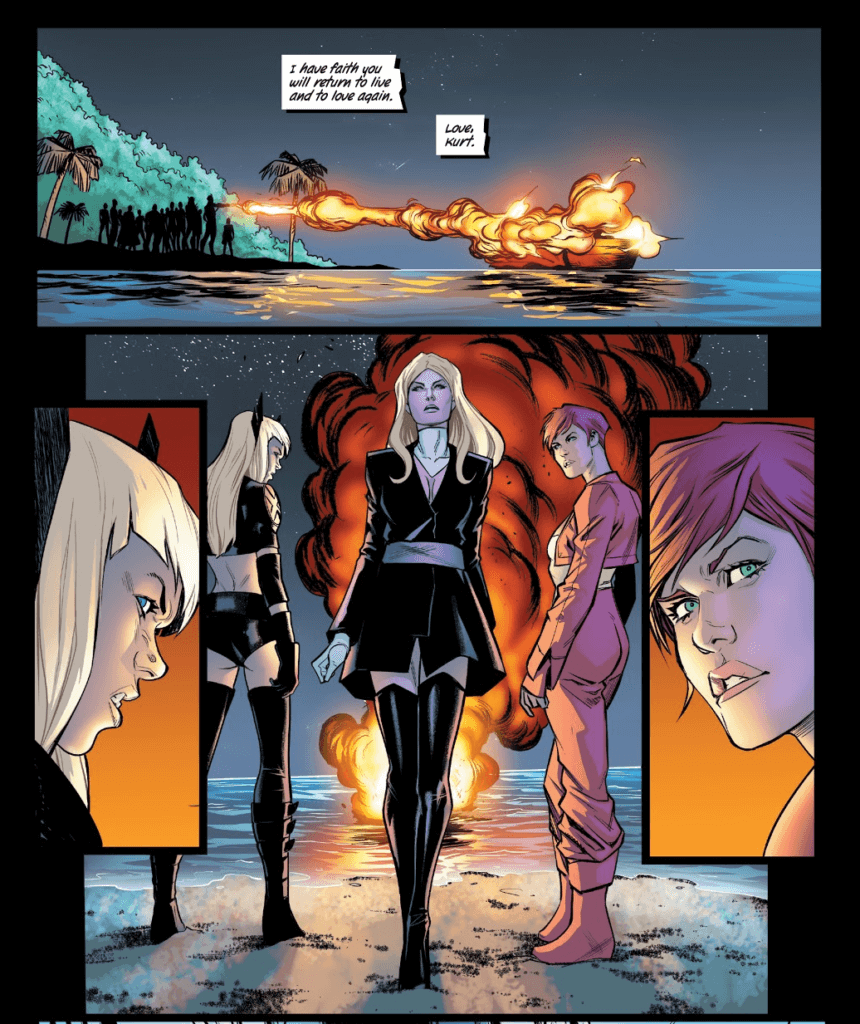

In Marauders #6, Kitty is killed by Sebastian Shaw, who supposes out loud that whatever it is that keeps Kitty from entering Krakoa via the doorways will also keep her teammates from resurrecting her via Krakoa’s methods of transplanting a dead mutant’s consciousness into a newly grown body. This assumption seems to be correct and, despite attempts to resurrect Kitty on Krakoa, she remained stubbornly dead for several issues. (At this point I could suggest she was just trying to get a break from all these goyishe happenings. Nice try, Kitty.) In Marauders #11, having accepted the less than temporary nature of her death, the inhabitants of Krakoa decide to cremate Kitty.

I will say that again, more bluntly: a murdered Jewish woman had her body disposed of by cremation.

While cremation is not historically a Jewish funerary practice, which dictate that the deceased should be buried without adornment in a plain wooden coffin — something else Marauders #11 fails to depict — there is a much bigger issue that needs to be addressed when it comes to the burning of Kitty’s body. During the Holocaust, millions of Jews were murdered by gas chamber and other means, their bodies disposed of by cremation. Jewish children were shown the rising smoke by Nazi guards, who pointed and told them that’s where their parents went. An extremely common antisemitic verbal attack involves telling Jewish people to get in the oven. For many there is simply no way to separate the act of cremating a Jewish character from the violent and hateful murder of their families.

What an insult, then, to take one of pop culture’s most iconic Jewish characters, a character who has been outspoken about the Holocaust and concentration camps, who has fought against the persecution of others, and have her non-Jewish friends and family send her off by cremating her body. Magneto, a Holocaust survivor, is depicted in the crowd during this cremation, although of course he is not allowed to speak. No one even attempts the Mourner’s Kaddish, the Hebrew prayer for the deceased. And while it would have been very easy to invent a one-off mutant rabbi to lead the service, there is none present. There is no melding of invented mutant and real Jewish traditions here, but instead a flat out rejection of Jewish traditions. The mutant metaphor becomes a problem when it allows the fictional to take priority over real marginalized identities.

Gerry Duggan responded to criticisms of the issue on Twitter, citing that the funeral acted as a “misdirection” to cover Kitty’s resurrection, but the problem isn’t the act of holding any funeral. The problem is the refusal to portray a Jewish funeral. The problem deepens because the decision to have Kitty cremated not only refuses to respect her as Jewish character during an issue where she is ostensibly the emotional heart but because it also invokes the violent deaths of millions of real life Jewish people, something Duggan either doesn’t understand or has chosen at this time not to address.

It would be bad enough if this act of cremation was carried out by anti-mutant bigots, in what could be viewed as a continuation of Marvel’s long history of using the fictional mutant struggle against anti-mutant violence as a metaphor for Jewish persecution and acts of antisemitic violence. At least then an argument could be made that this is Kitty, rising from the flames of that hatred, a Jewish woman stepping from these symbolic fires unburnt. It’s a scene that could be powerful if it was done with care and sensitivity, and, to be blunt, an actual focus on Kitty. Metaphors like this are tricky; if they aren’t executed successfully, you risk offending the group the metaphor aims to represent and empower. Judging by not just my own reaction but the reactions from many Jewish readers on social media, Marauders #11 doesn’t flawlessly pull this one off. This isn’t Kitty rising from the flames of hatred because Duggan has this act of violence against Kitty’s Jewish body carried out by her friends and found family, the people who are supposed to love her and who have demonstrated with this act a complete lack of respect for her. If Marauders #11 invoked this imagery in an attempt to disquiet all its readers, to stir within everyone a sense of unease at Kitty’s Jewish traditions being tossed to the wind, a portent of darker things to come, then it didn’t succeed there, either.

“There will be no cemeteries on Krakoa,” Nightcrawler writes in a letter to Kitty. It becomes more important on Krakoa, an island of the undying, that Kitty’s body not symbolize the failure of their system to cheat death than it is for her loved ones to honor her by her Jewish traditions and give her a Jewish burial. It becomes more important to dedicate the page time to non-Jewish characters reacting to Kitty’s death than it is to take the opportunity to depict what could have been one of the few Jewish funerals in pop culture history. Kitty cannot be buried because that would go against what Krakoa stands for, while they display no thought, not even a moment of hesitation, towards what she, as a Jewish person, would have wanted in death. Instead we’re left with an issue where a Jewish character’s body is cremated for the emotional catharsis of non-Jewish characters and, by proxy, readers, with no apparent thought for how Jewish readers might feel seeing Kitty’s body burned.

The X-Office at Marvel has been taking strides to build an immersive mutant culture on Krakoa, and with this one line they’ve elevated their fictional culture above a real one — but not above all real ones. After all, Kitty’s funeral is not a ceremony devoid of all pre-existing tradition. She is fully clothed in her open casket, a nod to Christian burials where the body is dressed and embalmed in order to be viewed. The coins on Kitty’s eyes are Charon’s obol, an offering to the ferryman of Greek mythology; one coin to pay the way across the river Styx to the realm of the dead and one coin for the way back. And the burning ship is doubtlessly meant to invoke a Viking funeral. In no way can it be claimed that this is a truly secular service, just one devoid of Jewish traditions.

What an utter betrayal of everything the character stood for for decades. What a disgrace for a company, let alone an industry, that would not exist without the efforts and genius of Jewish creators. The mutant minority metaphor cannot work when by attempting to invent a completely fictional society it invokes the trauma of millions of real life minorities while simultaneously trampling over their representation.

Marauders #11 pays an extremely token bit of lip service to Kitty’s Jewish identity at the very last second, when Nightcrawler smiles over the fact that it took eighteen husk bodies to resurrect Kitty. Eighteen is the numerical value of the Hebrew word “chai,” meaning life. This would be a meaningful scene if it hadn’t followed on the heels of the burning of Kitty’s first body, but a little unexplained wink to Kitty’s Jewish identity doesn’t make up for — however unintentionally it might have been — invoking the violent deaths of millions of her people. I love Nightcrawler and his friendship with Kitty, but to have Nightcrawler, a character so Catholic he was once almost the pope, slide this information along feels disingenuous and borderline offensive. It positions a Christian character as the keeper of this Jewish knowledge rather than allowing a Jewish character like Magneto or Iceman to voice these thoughts about Kate’s resurrection in an issue already full to the brim with non-Jewish characters deciding what is best and most honorable for Kitty’s Jewish body. To have a Catholic character invoke the number eighteen without any other explanation in the issue is, to put it simply, not enough.

“We are not here to bury Kate Pryde,” says Xavier during Marauders #11. They’re only here to bury her Jewish identity. Kitty can only resurrect now that one more shovel of dirt has been thrown on it, one more piece of her lost.