Like so many children from marginalized groups, Maurice Broaddus wanted to see himself in the media that he saw on the screen or in the books he read He wanted to be able to see people who looked like him shaping the future, whether it be commanding starships or wielding magic. Like so many of us craving that representation, he grasped at it wherever he could find it, from the X-Men’s Storm, to Cyborg, to Black Panther (of which he owns a complete collection, including T’Challa’s first appearance), to the best Star Trek captain, Sisko (Broaddus’ words, not mine, though I’m hard pressed to argue and will not take him up on the challenge to fight him about it, no matter how I might feel about Picard!)

When Broaddus did truly find works by and for black people, including Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Walter Mosley’s Futureland, the impact was profound.

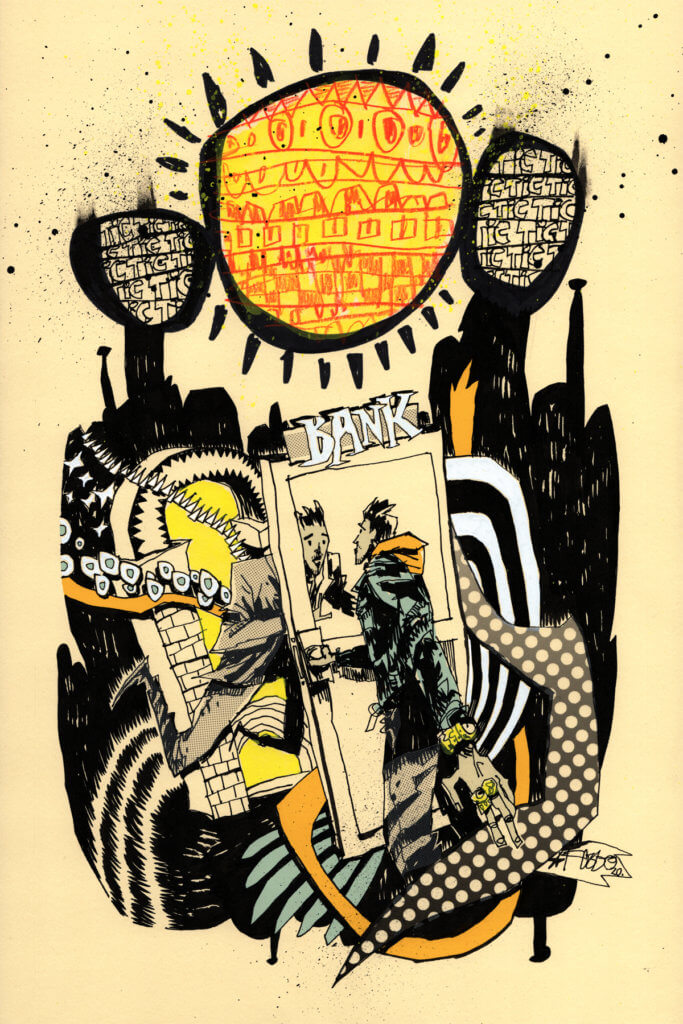

Now, as the landscape of speculative fiction expands exponentially with greater diversity, Broaddus himself is contributing to that wealth of imagination and exploration with Sorcerers, the flagship publication of the new digital publisher, NeoText. The urban fantasy novella, which is co-written Otis Whitaker, and features art from Jim Mahfood, tells the story of Malik, a young man from Harlem who learns from his dying grandfather that he is a sorcerer.

“Now it’s Malik’s turn to step up and take his place as wielder and guardian of an ancient magic passed down through generations in order to protect the family, the people of Harlem, and the world from the forces of dark magic connected to the worst aspects of American history and the fearful creatures it has unleashed.”

A science fiction writer with a strong passion for Afrofuturism, Broaddus’ work has appeared in Lightspeed Magazine, Weird Tales, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Asimov’s, Cemetery Dance, Uncanny Magazine, and more. He also serves as the Afrofuturist in Residence at the Kheprw Institute where he strives to improve the community by finding and connecting the many talented and skilled people within it.

Ahead of its August 4 release, Broaddus took some time to answer a few questions about Sorcerers and Afrofuturism.

What does Afrofuturism mean to you?

The idea of Afrofuturism has seen a recent resurgence in interest since the term was first coined by social critic, Mark Dery, in his 1994 essay, “Black to the Future.” When most people think about the term these days, it’s in light of the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s blockbuster, Black Panther. But Afrofuturism is what black creatives—black people, period—have always done: imagine a better future for ourselves. From Martin Delany and his book Blake (aka The Huts of America) to W. E. B. Du Bois’ story, “The Comet;” to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Water Dancer, and N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth Trilogy; from the visual art of Jean-Michel Basquiat the music of Sun Ra, Parliament-Funkadelic, or Janelle Monae to the work of Milestone Comics, Afrofuturists ponders the questions “Where are we now?” “Where do we want to be?” and “How do we get there?”

What does it mean to hold the title of Afrofuturist in Residence?

Being the Kheprw Institute’s Afrofuturist in Residence represents a public statement of the attitude and mindset of the organization and community, about creating desired future states in the present by constantly re-imagining the work and the way the community moves through the world. Afrofuturist-in-Residence means I am a part of the organization’s rhythm of dreaming together. As a community, we envision a desired future state that we can work toward.

Why did you feel that the novella format is the best way to share your stories?

I’m glad to see the novella making a comeback. It used to be the go-to length for books, but fell out of favor for decades. I’ve always gravitated to shorter works (look at me writing over a hundred short stories compared to a half dozen novels). And now with Sorcerers, I have a smooth half dozen novellas under my belt now.

Novellas are “armchair length.” By that I mean I can curl up in an armchair and consume the story in a single sitting. A short story or a comic book, I’m looking at ten to twenty minutes of escapism (a more crass interviewee would refer to them as “toilet sitting length”). A novel, well now I’m looking at 15 hours plus. A novella allows the reader to become immersed in, engrossed in, and thoroughly explore a world in a few hours. With the option to quickly revisit it.

At mauricebroaddus.com, readers can find various blog posts and resources, as well as his thoughts on the Kheprw Institute’s regular panel series, Afrofuture Fridays: “The theme of our Afrofuturism Fridays discussions is to ponder the questions ‘Where are we now?’ ‘Where do we want to be?’ and ‘How do we get there?’ because we have to imagine the future we want to see.”

As a teacher, you are also a learner. What have you learned from others in your Afrofuturism Fridays events? Have others answered these questions in ways that have surprised you?

Here are some personal highlights from Afrofuture Fridays:

Black Panther – this was our first one. The term Afrofuturism catapulted into the cultural consciousness with the release of the movie. We discussed the history of the character in comic books and the movie and applied the themes to what we see going on in the community today. It was a sometimes fraught conversation, dealing with various tensions and issues of identity, community, and agency within the community.

Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes/Tobias Buckell – we brought in these authors (Tananarive and Steven via Skype) to interview them and talk about Afrofuturism and their works (the term Afrofuturism came about because so few African Americans were writing it. Mark Dery, who coined the term, name-checked Octavia Butler, Samuel Delany, Charles Saunders, and Steven Barnes as some of the only practitioners at the time). It was an honor to talk to authors I looked up to and who had influenced me so much (Tananarive and Steven) and a friend who I’ve come up alongside (Tobias).

Clint Breeze and the Groove – One of the things we like to highlight are local artists/practitioners. Clint Breeze and the Groove had just released their first album, Arrival, with a pure nod to Afrofuturism. So, we did what few musicians get to do: have a panel to talk about the message of their work. Turns out, the vision was rooted in social activism, such as dealing with current issues like gentrification, and dreaming of a better future of social equity.

But our most recent Afrofuture Friday involved a bit of a reversal. Rasul Palmer is someone I’d been mentoring within the Kheprw Institute (as my co-facilitator of Afrofuture Fridays) and Madebo Fatunde, someone I’d been mentoring through the Science Fiction Writers of America. Well, I interviewed them about their work as black futurists, as both are leading tech heavy initiatives.

“We must fight oppressive systems, but, as an Afrofuturist, I’m still dreaming of better days,” writes Broaddus in his blog on the “Protests and the Value of Disruption.”

What are the three most important elements of the future you want to see?

1) Collapse of old, non-sustainable systems that never served people equally

2) Healing from the history of damage from those oppressive systems

3) Building of new systems, ways of moving, being, and doing

AND/OR

1) Change how we value relationships, supporting and celebrating each other

2) Change how we value art and science, storytellers and teachers

3) Change our competitive models to a cooperative, collaborative infrastructure, that impacts how we do our economic models to education to policing/criminal justice.

We can re-imagine a better future. Together.