“Once upon a time, there was a woman who could fly.”

– Uncanny X-Men #186, “Lifedeath”

X-Men #7

VC’s Clayton Cowles (letterer), Sunny Gho (colorist), Jonathan Hickman (writer), Tom Muller (design), Leinil Francis Yu (artist)

Marvel Comics

February 26, 2020

The X-Men have always known death. For every generation that has read X-Men comics, there’s the death, the shocking blast of an ending that Changed Everything Forever. Little Illyana Rasputin, sick with the Legacy Virus. Dark Phoenix dying on the moon. You could even go back fifty years to X-Men #43, to the first death of Professor X (later revealed to be the forgotten former foe Changeling). But the X-Men also know rebirth; the luckiest, most uncanny mutants – like Illyana, Phoenix, and Professor X — always come back from the dead, sometimes more than once. It’s become a cliché, as genre-savvy readers know that for most superheroes, death is just a pause, not an ending. How do you engage readers who have become deadened to death?

Here’s one way. X-Men #7, by Jonathan Hickman and Leinil Francis Yu, takes a long-held idea to its literal conclusion – death is a rite of passage for mutants. (Anecdote time: in my one conversation with Chris Claremont, he talked about an X-Men story idea in which recently resurrected characters like Nightcrawler, Psylocke, and Kitty Pryde would throw a “We Came Back from the Dead!” party. Marvel rejected it.) Through the new ritual of Crucible, death and rebirth become formally ingrained in mutant culture. It’s an ingenious bit of worldbuilding from Hickman that answers the question “What about the one million mutants depowered on M-Day?” while stirring up many more.

X-Men #7 takes its title, “Lifedeath,” from the acclaimed issue by Chris Claremont and Barry Windsor-Smith that dealt with Storm’s emotional recovery after losing her mutant powers. Unlike Giant-Size X-Men #1, this isn’t a homage to an older issue; still, Uncanny X-Men #186 is worth keeping in the back of your mind as you read about Melody Guthrie, the depowered mutant formerly called Aero. Once upon a time, Melody could fly. That gift was stolen from her on M-Day, and her feet have been on the ground ever since. Not human but no longer a mutant, either, she’s been trapped in a kind of half-life. Death, life, Lifedeath. But that’s about to change since Melody’s been chosen for Krakoa’s first Crucible.

The mystery of Crucible unfolds slowly, as the story shifts to the Summer House on the moon. A charming scene of domestic intimacy (the quick hits: robe! Coffee! Bikini! Speedo!) between Cyclops and Wolverine shifts into something more ominous as the men discuss Crucible and their uncertainties about it. A comment from Wolverine — “Go find a priest” – sends Cyclops to seek out Nightcrawler, and an interesting interlude occurs. Nightcrawler points out the forked towers that have been part of Krakoa’s landscape since House of X/Powers of X.

Since the towers have no visible entrance, Nightcrawler took a risk – took a leap of faith – and teleported inside, only to discover a white, cathedral-like interior that looked like it was made only for him. (I’m reminded of Grant Morrison’s Phoenix describing the White Hot Room: “You were always here, waiting for yourself to arrive.”) The white towers could be the organic twins of Nimrod the Lesser’s tower, that “pillar of collapse and rebirth” which is first glimpsed on a Tarot card in Powers of X #1, alongside Cardinal, Nightcrawler’s chimeric descendant, who followed “the last religion.” I never wondered what that religion was, but by the end of X-Men #7, I might have seen its beginning. Before Nightcrawler has that last page epiphany, however, he has questions – namely, “Are we really going to sit around and watch a mutant die?”

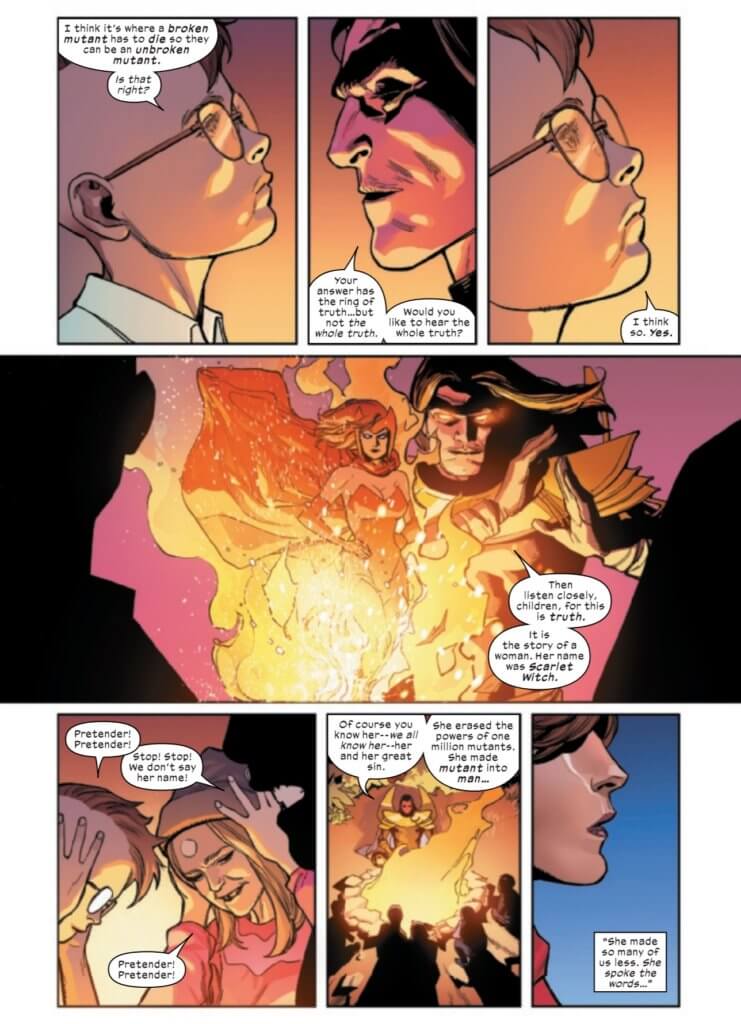

To understand Crucible, we have to return to the trauma of M-Day. By firelight, Exodus tells a group of children about the Decimation, and the mere mention of Scarlet Witch’s name is enough to make kids cover their ears and scream “Stop! Stop! We don’t say her name!” Now, the fact that Scarlet Witch has become a literal witch used to scare mutant children in front of campfires is first of all very funny, but also very fitting. (Kudos to Yu and colorist Sunny Gho for making Scarlet Witch look utterly devilish as her image is conjured in Exodus’s flames.) It’s been fifteen years since House of M, and despite AvX and numerous retcons designed to mitigate Scarlet Witch’s culpability in depowering one million mutants and keep her as a viable (and profitable) Avenger, “No more mutants” is still her lasting legacy on the Marvel Universe. Though this is an essay for another day, I’d argue that the retcons have made Wanda’s actions worse – no longer a mutant, “The Pretender Wanda Maximoff” is now one of them, one of the humans who have tried to wipe mutants off the face of the Earth. And of all of them, she came the closest to succeeding. Are we surprised that the same mutant children are reclaiming her words and spitting them back at their would-be destroyer? “No more.”

To understand Crucible, we have to return to the trauma of M-Day. By firelight, Exodus tells a group of children about the Decimation, and the mere mention of Scarlet Witch’s name is enough to make kids cover their ears and scream “Stop! Stop! We don’t say her name!” Now, the fact that Scarlet Witch has become a literal witch used to scare mutant children in front of campfires is first of all very funny, but also very fitting. (Kudos to Yu and colorist Sunny Gho for making Scarlet Witch look utterly devilish as her image is conjured in Exodus’s flames.) It’s been fifteen years since House of M, and despite AvX and numerous retcons designed to mitigate Scarlet Witch’s culpability in depowering one million mutants and keep her as a viable (and profitable) Avenger, “No more mutants” is still her lasting legacy on the Marvel Universe. Though this is an essay for another day, I’d argue that the retcons have made Wanda’s actions worse – no longer a mutant, “The Pretender Wanda Maximoff” is now one of them, one of the humans who have tried to wipe mutants off the face of the Earth. And of all of them, she came the closest to succeeding. Are we surprised that the same mutant children are reclaiming her words and spitting them back at their would-be destroyer? “No more.”

And from the mouth of babes comes a clumsy explanation of Crucible: “It’s where a broken mutant has to die so they can be an unbroken mutant.” The unfortunate use of “broken” aside, that’s close enough. Nightcrawler, the swashbuckler-saint of the X-Men, guides us along with Cyclops to the arena, explaining Crucible’s origins; this is an ideal role for the character because we trust him innately. His questions are our questions. One of the gifts of the Resurrection Protocols is that depowered mutants can be reborn with their powers restored; of course, you can’t be reborn without dying first. Crucible is an act of ritual combat in which a depowered mutant will fight Apocalypse to the death so that they can be reborn – and that’s exactly what happens when Melody, clad in an X-Men training uniform and a flower crown like a sacrificial maiden, steps into the arena. It’s violent. It’s brutal. It’s tough to read. But here’s the brilliant thing – it never feels like a defeat. It’s a victory.

Crucible is a ritual of choice. That choice is immediately offered to Melody; her sister Husk stresses that Crucible will happen only “If you want it.” And during combat with Apocalypse, she’s offered an exit and healing, but she refuses. Rather than accept victimhood, she overturns it – she can’t pick up a sword and fight Scarlet Witch or the human bigots that would kill her, but she can fight Apocalypse, whose particular brand of pompous negging takes the form of any self-doubts and self-recriminations Melody has had since she was depowered. Leinil Francis Yu, returning to regular art duties after being away for two issues, does fantastic work during this fight scene; it looks like it hurts, with Melody alternating taking Apocalypse’s blows like a broken doll and standing up, fists raised, bloody but unbowed. She’s fighting for herself, her true self, and she will no longer be depowered or diminished in man’s world. Why is she here, Apocalypse asks? “To fight and die for my people. Like a mutant.” But death for mutants doesn’t necessarily mean what it used to. Melody isn’t choosing the abyss, but survival.

X-Men #7 is a fascinating slice of science fiction from Hickman and Yu. It asks hard questions of the characters and readers; at least, harder questions than we usually get in superhero comics, like whether you’re Team Iron Man or Team Captain America. Several months into Dawn of X, we now know the issue is not in the Resurrection Protocols themselves (or if they’d, ironically, kill all drama and momentum in the X-Books) but how the characters would react to them. X-Men #7 raises questions about agency, bodily autonomy, culture, and faith that are new to the franchise, and they’re thrilling. The blossoming mutant society on Krakoa pushes against human ideas of normality, and if they still feel alien or chilling, well, we’re all flatscans, technically we’re the ones trespassing here. It is emphatically not a cult or a hivemind, despite what online detractors have argued; reactions to Crucible are split, as Wolverine refuses to attend, and even Husk, who knows Crucible is “what [Melody] wants,” has to be held back when the fight intensifies. Crucible is a reminder that the X-Men will always know death, but it won’t destroy them.

There are scenes of brutal violence in X-Men #7, but more striking to me are the moments of hope and faith. Nightcrawler’s leap of faith teleporting into the towers. Melody’s faith that after she dies, the Five will resurrect her. Cyclops’ faith that, after his resurrection, he is still himself in all the ways that matter. Melody again, in two of the most powerful panels Yu’s drawn yet, having faith that she will fly again. Mutants still have to figure out their place in a strange new world. Cyclops and Nightcrawler still have questions. Melody – Aero – has her answer.

There are scenes of brutal violence in X-Men #7, but more striking to me are the moments of hope and faith. Nightcrawler’s leap of faith teleporting into the towers. Melody’s faith that after she dies, the Five will resurrect her. Cyclops’ faith that, after his resurrection, he is still himself in all the ways that matter. Melody again, in two of the most powerful panels Yu’s drawn yet, having faith that she will fly again. Mutants still have to figure out their place in a strange new world. Cyclops and Nightcrawler still have questions. Melody – Aero – has her answer.

“My feet may never leave the ground…but, someday, I shall fly again!”

– Uncanny X-Men #186