Editor’s note: Ah, San Diego Comic Con. What a time, what a place! I’ve never been. But I have been caught up in the press of it all, getting interview sorted, then rearranged, then having to do them myself, then realising I should have done it yesterday by email. Ah, San Diego Comic Con…

So instead of all that what we have is this: F Stewart-Taylor, she of The Trades and the biggest John Allison Presents fan I know who isn’t me, asking Sweet JA all the questions in her heart. It was supposed to be an SDCC thing, but because of certain reasons it became a Q&A in GoogleDocs. That’s okay though! What matters is that the answers, and they are here. Please enjoy. And thank you. Good day.

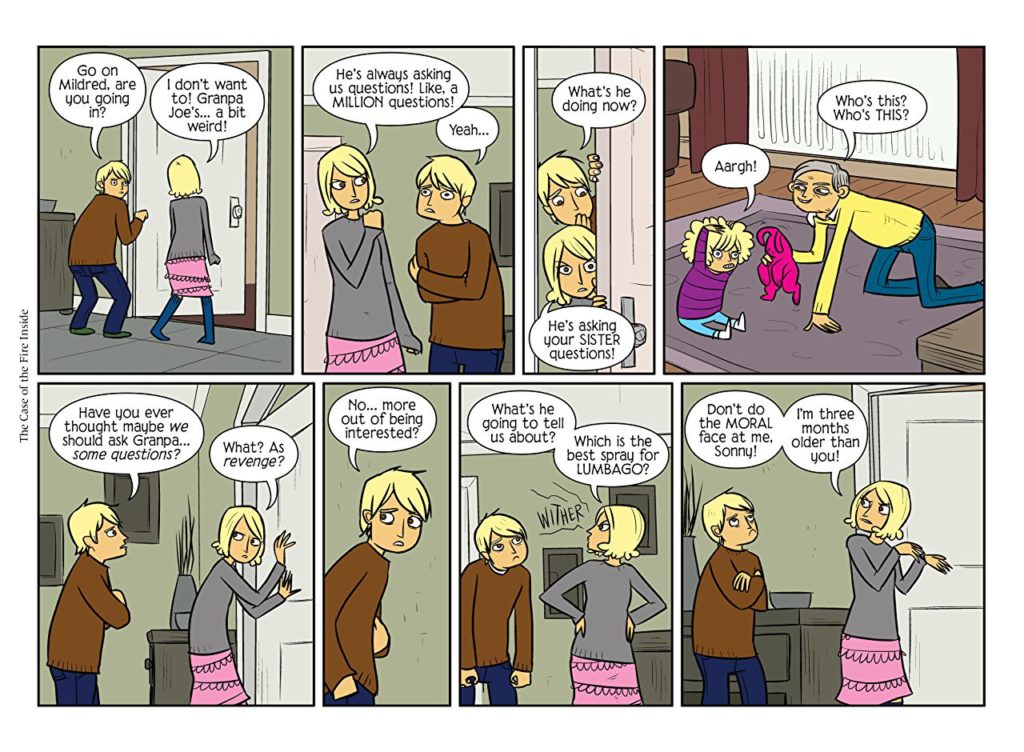

Hi John. It’s a delight to have the opportunity to ask you a couple questions. I’ve been a fan of yours for years, and there’s so much I love about your work. I tried to focus on the Bad Machinery case for which you received the Eisner nomination, The Case of the Fire Inside, but there’s a bit of everything.

First of all, obviously, congrats on the Eisner nomination, which is richly deserved. I believe this was your third Eisner nomination, the first two being for Giant Days, which is a monthly comic distributed more traditionally, and you won the Web Cartoonists’ Choice for Scary Go Round a couple times. Do you feel like you have a foot in both print and webcomics with Bad Machinery being published by Oni? Does it feel more like a webcomic, or more like a print comic that is also published on the web, and did that change as you brought the series to a conclusion? What are you excited about, format wise, in comics lately, on or off line?

Pitching Bad Machinery for print was an abstract act—it was a webcomic that I wanted, by force of will, to make into a proper book. I’d collected all the Scary Go Round strips into books that I’d published myself so it seemed like a step to formalise that process. In retrospect, of course, it was still very much a webcomic, formatted like one and written like one—on the hoof. As I had with my early webcomics, I had to learn on the job—painfully slowly—especially as Oni were very hands-off and pretty much let me publish what I wanted.

I’ve got back into print comics in the last few years, but format is always secondary to content. Is the work good? Does it press my buttons? I’ve drifted out of webcomics over the years, discovering new things has become harder as the community fractures.

Although you phased out some of the supernatural elements as the Mystery Kids became Mystery Teens, The Fire Inside, which earned the Eisner nod, has some of the cleanly integrated thematic supernatural elements in the whole run of the series, what with seals becoming girls and boys becoming slightly older and more hormonal boys. In a Comics Alliance interview, you called the inclusion of supernatural elements, although perhaps not your inclusion of supernatural elements, ‘magical realism’ and I was curious if you felt that your inclusion of such elements shared anything in particular with magical realism as a genre with a particular literary history, or if it has more in common with folklore and urban legends. In other words, what do you see as the relationship between the supernatural, the town of Tackleford, and your broader storytelling interests and aims, particularly in Bad Machinery?

I wanted the series to be about folklore and urban legends. I carefully researched spirits and creatures and tried to incorporate them into child mystery plots. Research for the child mystery plots consisted of reading one Hardy Boys book and one Nancy Drew book, declaring them boring, and deciding to do whatever I wanted.

One thing I discovered researching folk beasts was that they were almost all the same, or variations on one or two themes. Which is why by the fourth case aliens have manifested, the sixth case is about a giant walnut, and the seventh is a time travel epic. The interplay of the child characters, on the other hand, seemed incredibly fertile territory. The vanishing of the supernatural in the last two or three cases was more about the end of innocence than a rejection of magical realism. After all, the final case involves a weird blood curse, an imp that is stuffed down a toilet, and a living, evil, fatberg.

There’s no formal process in any of this. To my mind, Tackleford is just a weird town where outlandish things can happen, but it also has an earthiness and an ordinariness that rejects the old Sandman/Books Of Magic/Shade the Changing Man Vertigo comics’ magically real psychedelia. I’m all for that sort of thing but it doesn’t play to my strengths.

In a CBR interview, you described the Scary Go Round adults as acting ‘drunk all the time,’ and it seems like you’ve been reconsidering through them, or having them reconsider, their position as adults very directly in recent strips. What was it like for you to position the kids in a social world with relationships to the adults, like Ryan and Shelley, who you wrote for years as not-quite-kids? Did it change how you think of your characters, to see them in this new context or to decide how the kids see them, and vice versa? Did writing the kids growing up change how you saw the future for the Scary Go Round characters, or is it more like both are expressing a theme in which you’ve been interested for a while?

I see the Bobbins characters as one generation, the characters introduced in Scary Go Round like Erin, Eustace, Esther and so on a second generation, and the Bad Machinery kids as a third generation. Each has a new layer of sophistication. Trying to get them to interact has required a layer of sophistication to be applied to the old characters in order that the interaction works, and in a lot of cases, that has meant sidelining or removing “legacy” cast. This is inherently a bad thing, to my mind. There shouldn’t be a “legacy cast.” A shared universe is fun, but it’s also cumbersome and annoying. The new Bobbins stories I’ve done are meant to harmonise these worlds, but they’re rabbit holes that always take months to write my way out of. They start off fun, but following their logic to its bitter end is just ghastly. It takes a year or so before I look back and feel like the process was worth it. Those stories are deep reads for mega-fans.

Shauna’s affection for Brutalism seems to me to have a potential connection with her working class background and early years on a council estate; that kind of rich detail about kids’ interests and family lives are thick on the ground in Bad Machinery. They’re age appropriate in subject and style of passion, which is charming and another avenue into how these kids develop over time. How has your process for creating characters changed, to get to the more emotionally grounded characterizations you’ve given the kids? What does that process look like, and how does it fit into your writing process, which sounds like it involves pretty extensive planning?

The characterisations just occur to me as I write. There’s no master document that says what Charlotte or Shauna likes. A door appears and I step through it. It was funny to me that a 12-year-old would like Brutalist architecture. It was funny to me that Charlotte would love death metal and Death Note, but it felt real. I just kind of know!

The Fire Inside is at a delicate moment in the growing up of young persons; reading through some of the old cases, it’s interesting to see both how your art has changed, and how you’ve changed the kids’ features and personal style as they grow up. Putting Charlotte in blazers is a bit of genius, I think. Would you talk about your visual design process for characters, and particularly how you’ve thought about the kids’ growing up and changing, visually?

The girls have very strong visual identities. Lottie, who is perhaps the most childlike of the three in her personality, is desperate to be seen as more grown-up. So I gave her that bun, the blazers, the button-down blouses, and her Paul Westerberg suit. In the final story, Shauna is wearing her Saturday job boss Amy’s old hand-me-downs because her brother destroyed almost everything she owns, a signifier of the mentorship Amy has provided. And Mildred, an only child, has some odd fashion choices. She’s working out who she is.

The boys, apart from their spell as mods, dress in the generic outfits of teen boys. Jack is a little cooler than the other two and has some fancier attire, but in the last case they’re full-on Three Investigators in their suits—just a nod to the books I’d started out wanting to emulate but quickly ignored. There’s a thought behind every outfit.

With some exceptions, the kids investigate mysteries more than crimes per se, but do you feel like there’s a connection between your work and the rich world of British Crime Fiction? I’m thinking more Marple than Morse, since I can picture Charlotte in 60 years as a particularly noisy Ms. Marple type sleuth; the Jessica Fletcher connection being already explicit in Murder, She Writes. Do you feel like there’s a connection between your Tackleford mysteries and the ‘cozy’ mysteries, in terms of how the fabric of community is woven through with intrigue?

I remember with great pleasure watching Sunday night mystery shows with my parents as a teenager. As I like to say often, the perfect show to watch with your mum and dad is one where there is absolutely no chance of anyone ever getting a blowjob. Murder, She Wrote is at the back of my mind, also The Ruth Rendell Mysteries, Bergerac, Lovejoy, and of course Poirot and Miss Marple.

Do you feel like working with a publisher, on Bad Machinery particularly but also Giant Days, has changed your relationship to comics and comics readership? You mentioned that you feel like webcomics are being competed against more and more for bits of leisure time; do you think print comics are more sustainable in terms of reader attention, or is it more a question of what the expected and desired readership buy-in for a print comic is?

The difference is that people in the industry know who you are. Doing a webcomic meant blank looks among all but the hippest people working in the mainstream when you met them. That has changed a little, but I don’t think it’s changed a lot. And I wanted to be known in the industry—I’d been reading their comics since I was 6 or 7. Webcomics are past their peak. People don’t visit websites like they used to, but at the same time, there are far more places for people writing the sort of material I have been working towards to do it in print now than there were a decade ago. It’s hard doing everything on your own. It’s bloody exhausting and I was getting very tired of it, as the hill grew ever steeper.

Are print comics more sustainable? I have no idea. But there’s a framework and an infrastructure that makes sense to readers. The infrastructure for webcomics as a stable art form has become ever more nebulous as social media has grown.

What have you most enjoyed exploring through Bad Machinery? Has working on the series been a growth outlet for you? What do you foresee taking from this project to your next endeavour?

Working on Bad Machinery has been a huge opportunity for growth as a writer. The longer stories have given me tremendous room to develop my characters and develop my plotting. Both of those things have been of great value on Giant Days, and can only help me as I go on.

As concerned as I am about the future for webcomics, I remain a fan of the form. I love strips, serials, and episodic entertainment, and applying the brevity of the newspaper comic to a more dynamic medium. I’ve been doing webcomics near-daily for almost 19 years. They mean something to me. Bad Machinery wound up being a weird hybrid, half book, half webcomic, but I would not have had it any other way.