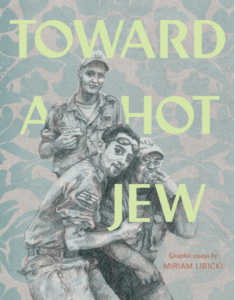

Toward a Hot Jew: Graphic Essays by Miriam Libicki

Miriam Libicki

Fantagraphics Books

September 28, 2016

For every human being stuck between two or more axes of oppression, the internecine fighting of intersectional politics can be as frustrating and upsetting as hatred. As sick and horrified as I felt at recent acts of Antisemitism inspired by the election of Donald Trump — the most notable when “alt-right” white supremacist Richard Spencer spewed hate speech to an audience who responded with Nazi salutes — for much longer I’ve also associated Antisemitism with common, leftist dismissals on places like Tumblr.

Some Jews have money and success, so Jews can’t be oppressed. Israel was created after the Holocaust, so Jews can’t be oppressed. Most Jews are white, so Jews can’t be oppressed. Jews have been racist, so Jews can’t be oppressed.

Most of these statements come up by other minorities in response to posts about Antisemitic hate crimes or pleas to include Jews in activist movements. For the most part these are meant as silencing tactics and not the start of hard conversations about how some Jews can conditionally access white privilege, issues of appropriation and cultural supremacy among the different Jewish ethnic groups, or how to Jews can deal with intra-community racism. Fortunately for Jewish readers looking for a way forward, writer/artist Miriam Libicki’s graphic essay collection Toward a Hot Jew provides a good place to start those conversations.

Toward a Hot Jew features seven pieces. Most of these deal with Jewish identity or the internal politics of Israel, but the first — “Who Wants to Be an Art Star” — is a decent introduction to what Libicki does. In creating one-page profiles of herself and her fellow students at Emily Carr Art Institute, Libicki writes a contiguous text about the artist. This text is broken up over a splash page or panels drawn in watercolor and ink that showcase the artist, a facsimile of their artwork, or even just a close-up of a previous portrait to give the reader the impression of greater intimacy with the subject.

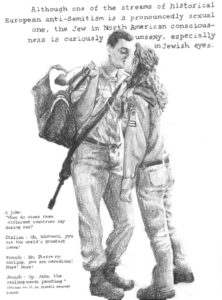

Libicki works mostly in pencil for the next piece — the book’s title essay “Toward a Hot Jew: The Israeli Soldier as a Fetish Object.” Libicki’s figure drawing is oddball. The details she puts into her subjects’ clothing and objects and the realistic shading strive toward realism, yet her figures’ wide-eyed expressions seem cartoonish. Still, her style is effective for this piece, which shows pictures of attractive young IDF soldiers interspersed with an essay on how the image of the strong, sexy, fighting sabra works as propaganda for Israel and a refutation of Jews being stereotyped as nebbish nerds, ball-busting materialists or eternal victims of the Holocaust. For me, this wasn’t new territory. I’ve heard these ideas discussed before in Forward pieces and Israeli novelist Amos Oz’s memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness, but it is a good presentation of the idea of Jews trying to remake their image via Israel becoming a double-edged sword.

Libicki works mostly in pencil for the next piece — the book’s title essay “Toward a Hot Jew: The Israeli Soldier as a Fetish Object.” Libicki’s figure drawing is oddball. The details she puts into her subjects’ clothing and objects and the realistic shading strive toward realism, yet her figures’ wide-eyed expressions seem cartoonish. Still, her style is effective for this piece, which shows pictures of attractive young IDF soldiers interspersed with an essay on how the image of the strong, sexy, fighting sabra works as propaganda for Israel and a refutation of Jews being stereotyped as nebbish nerds, ball-busting materialists or eternal victims of the Holocaust. For me, this wasn’t new territory. I’ve heard these ideas discussed before in Forward pieces and Israeli novelist Amos Oz’s memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness, but it is a good presentation of the idea of Jews trying to remake their image via Israel becoming a double-edged sword.

“Ceasefire” is a part-diary, part-series of portraits Libicki created during a trip to Jerusalem that happened to coincide with a ceasefire between Israeli and Hezbollah forces in August 2006. In watercolor splash pages, Libicki shows scenes of Israeli life peacefully existing, but the descriptions feature Libicki’s guilt about the situation and the subjects’ word bubbles describe their anxiety amidst the image of normalcy. She utilizes the same method for the later piece “Fierce Ease” about the pessimism of her Israeli friends and relatives circa 2008 in the face of perpetual war.

These pieces sandwich “Jewish Memoir goes Pow! Zap! Oy! — On Autobiographical Novels and Why They Are So Jewy.” Perhaps the collection’s greatest departure, the essay is an in-depth literary criticism on how the vulgar, confessional style of memoir comics are rooted in the work of novelists like Philip Roth and the Jewish Biblical tradition of portraying the “Chosen People’s” relationship with God as “raw and ambivalent,” as well as Libicki’s own place in this tradition. To a certain extent I have trouble attributing this style to specifically non-Jewish artists like R. Crumb, Justin Green or Craig Thompson, who I’m sure are influenced as much by their own cultures. Yet I do think the essay is one of the highlights of the book. It’s well-researched and critical of how these works often use the suffering of others as well as their own, and I like how Libicki imitates the styles of those she is discussing in critiquing them.

These pieces sandwich “Jewish Memoir goes Pow! Zap! Oy! — On Autobiographical Novels and Why They Are So Jewy.” Perhaps the collection’s greatest departure, the essay is an in-depth literary criticism on how the vulgar, confessional style of memoir comics are rooted in the work of novelists like Philip Roth and the Jewish Biblical tradition of portraying the “Chosen People’s” relationship with God as “raw and ambivalent,” as well as Libicki’s own place in this tradition. To a certain extent I have trouble attributing this style to specifically non-Jewish artists like R. Crumb, Justin Green or Craig Thompson, who I’m sure are influenced as much by their own cultures. Yet I do think the essay is one of the highlights of the book. It’s well-researched and critical of how these works often use the suffering of others as well as their own, and I like how Libicki imitates the styles of those she is discussing in critiquing them.

However, the best essay is the last in the collection — “Stranging the Welcomer: A Theory of Black and White Jews All Over.” Libicki worked for years on this essay. In the preceding piece, “Strangers,” about her feelings of impotence watching over social media the uptick in racist protests in Israel against the Sudanese refugees, she mentions wanting to write a piece about Ethiopian Jews. “Strangers” is good. It utilizes original sources of articles and social media protests (attributed via different-colored lettering) in a unique way, and I could draw parallels to my own feelings about the current backlashes against Syrian refugees in America and Europe.

Yet “Stranging the Welcomer” is an earnest attempt to deal not only with Jewish intra-community racism, but how conflicting narratives play into the struggle. The beginning goes through the history of how Israel saved many of the Bene Israel people from famine in Ethiopia via airlift to the country, but treated them poorly after their arrival — giving the refugees Depo-Provera without their knowledge and sometimes treating them as uneducated or mentally disabled for not being aware of touchstones of Ashkenazi (Jews of Eastern European descent, as opposed to the Sephardim of Spain and Portugal or the Mizrahim of the Middle East) culture and religious practice.

Libicki discusses how conditionally “white” Jews in Israel and America have used “Operation Solomon” as proof of Jews’ open-mindedness while ignoring the mistreatment of Ethiopian Jews in subsequent years, but also ties this into a myriad of other issues and contradictions in black and Jewish relations: the participation of Jews in the Civil Rights movement and Martin Luther King’s support of Israel, the flight of conditionally “white” Jews to the suburbs, Jews appropriation of African-American culture, and the Antisemitism of Louis Farrakhan. In this discussion Libicki tracks how Jews are cast in the role of oppressed or oppressor — the covetous villain of Christian imagination or the Zionists destroying the self-representation of Mizrahim — and points out the limitation of seeing disputes between peoples in such broad good vs. evil roles.

The book ends with a call to radical empathy, a call for Jews to understand those of their religion/ethnicity and other oppressed peoples different from them. It’s a familiar call, but one that’s needed, especially in a difficult time like this. If what we fear is the tendency toward stereotypes of the “other” in fighting oppression, stereotypes, and fascism, it’s best that these discussions occur in full contexts. Toward a Hot Jew isn’t perfect, but it’s one of the fullest and most unique attempts to have the discussion on intra-community Jewish racism that I’ve ever seen, and well worth checking out.