In a historical move, DC Comics has slated to publish their first comic book title led by a queer couple, Midnighter & Apollo #1, on October 5th. Midnighter and Apollo certainly aren’t the newest kids on the block, however. The two first appeared in 1998’s Stormwatch #4 by Warren Ellis, Bryan Hitch, and Laura Depuy (now Laura Martin) although their coming out occurred in 1999’s The Authority #8 by the same creative team. After that, they became among the most well-known LGBTQ superheroes.

Excited for the new title? We are, which is why we’re hosting this roundtable on Midnighter & Apollo’s Stormwatch debut, as well as three more through September that will cover The Authority, the first Midnighter solo arc by Garth Ennis and Chris Sprouse, and one of the last The Authority runs by Dan Abnett, Andy Lanning, and Simon Coleby. Read on to find us chronicling queer representation in superhero comics over the last 20 years as well as interrogating the definition of the modern superhero through these wonderful characters.

If you weren’t introduced to Midnighter and Apollo through the recent Midnighter title by Steve Orlando and ACO, you may have through the phrase “the gay Batman and Superman.” Let’s delve into the queer rep as it’s seen on the pages of Stormwatch. Immediate reactions?

Heather Knight: The idea behind a “gay Batman and Superman” is really appealing to me in the sense that while I love those traditional heroes who have been embraced by me and many other readers for decades, it would be nice if some of those heroes reflected me more, and other people in the queer community. Stormwatch was not my introduction to these two (it was The Authority), and as a queer person I’m used to trying to read between the lines of character exchanges, starving for representation and just hoping for something other than the hetero-normative in stories I’m consuming, so despite the ambiguity of their relationship in Stormwatch the prior knowledge that they’re gay superheroes made my reading experience more positive. Which might not have been the case had I read Stormwatch first. Midnighter and Apollo’s relationship isn’t very explicit in the text, but having two super powered men who don’t compete with each other in the name of hyper masculinity and instead have a supportive and genuinely caring partnership was also rare to see in a comic, but only more important to me because of the prior knowledge that they were also gay men in a relationship.

While I love those traditional heroes who have been embraced by me and many other readers for decades, it would be nice if some of those heroes reflected me more, and other people in the queer community.

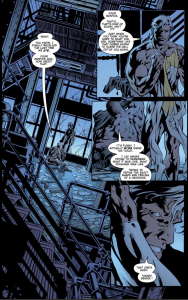

Ray Sonne: JAM, you’re not the first person to think that because actually, no readers of Stormwatch at the time of the comic’s publishing recognized the implication was that Apollo and Midnighter were sleeping together in more than the literal sense. There is subtext in that when it’s pointed out to you that there’s no reason for them to necessarily sleep naked (as shown in the later scene where they’re huddling fully clothed in the doorway) it dawns on you a bit, and Hitch also puts Midnighter in a kind of suggestive position in one panel. The threads are absolutely there, but they go deeper than subtle and become invisible. On its own, Stormwatch isn’t exactly great queer rep because it doesn’t want to admit that its queerness is there for whatever reason.

Meanwhile, two heterosexual couples are having on-page confirmed active relationships, which shows you the gulf between how the societally-accepted couple is depicted and what we get to see of the couple who doesn’t fall into that category.

Heather: Ah yes, the position where a naked Midnighter is on his knees in front of an equally naked Apollo, eye-level with his crotch region? Definitely not the most subtle imagery, especially if you’re looking for it, but considering Midnighter and Apollo are carrying on a conversation void of any actual intimacy despite being in that position and in various states of undress, I get why other readers might not have immediately caught on. Compared to other couples in the book, that’s still pretty casual for two men who are without clothes and had either just been sleeping or having sex (or both). They might as well have been talking about the weather.

Apollo and Midnighter were not “out” as of this book’s publishing. Instead, Ellis and Hitch depict their sexuality through subtext (which may seem heavy, but you may be surprised how many people didn’t recognize it). At the time, this strategy was necessary, but let’s talk about the use of subtext in queer stories today. Is its way of “getting things under the radar” still helpful or a bad shortcut in today’s world?

Heather: Midnighter and Apollo are introduced in the story completely naked and alone together, which for me may or may not have been all the heavy handed subtext I needed, but I can maybe see why others didn’t immediately jump to that conclusion. They’re not being openly affectionate with each other, in a book with other characters who are talking about their relationships and engaging in them intimately on the page. I think using subtext in queer stories today is often more damaging than helpful for the most part. This is 2016, we shouldn’t still have to fly queer themes under the radar to get them published and foster an audience. People want these books, they crave that representation without nuance. As a retailer in a comic book store, I see (and feel myself) more anger and annoyance than joy when queer readings are still left to the ambiguous subtext instead of openly calling it what it is. Can you imagine if this Midnighter & Apollo series was being advertised as two men who are just ‘super good friends’ and like to fight bad guys together? No, they’re gay, and a couple. That’s it.

JAM: In 2016, subtext is fine for secondary characters but I think flying under the radar isn’t doing anybody any favors. I’d be more encouraging of subtext here and there—but queer people are painfully absent from the mainstream. There is a culture of shame—or, I should say, there is a culture of shaming. Non-queer people have used every last piece of cultural capital to convince the masses that queer people do not exist and if they do, it’s in secret. And yes, subtext may be key in certain stories about closeting or coming out or the struggles of living in an oppressive world—but after decades of stories about quiet suffering, these days, queerness has got to be overt or I don’t have much time for it.

There is a culture of shame—or, I should say, there is a culture of shaming. Non-queer people have used every last piece of cultural capital to convince the masses that queer people do not exist and if they do, it’s in secret.

Heather: Yeah, I don’t have the patience for cop-outs where writers are making use of characters like that just to get points but not bother to actually develop any real story there. I’m all for the kind of subtext that eventually develops into something crystal clear, like you said in the case of a slowly developing relationship or in a story involving an initially closeted character. As long as there is some kind of payoff, I’m usually willing to be more forgiving in the long run. In Zodiac Starforce, Savanna’s sexuality wasn’t obvious to me until she began ditching her jerk boyfriend in favor of hanging out with Lily and I started catching the subtext vibe, so I was really glad when they actually took that relationship and made it explicit instead of drawing it out in a ‘girls who seem close and hang out together secretly’ kind of way. I also agree that it’s much less acceptable when it’s main characters getting the subtext treatment, and in the specific case of Apollo and Midnighter, that kind of ambiguity just would not fly today. We’ve come far enough that I hope we can handle boys kissing each other on the page in a comic book.

Although sex does often come up in prior Stormwatch arcs, its presence in this arc seems particularly central—Christine uses “the wet spot” to scold Jackson, Hellstrike and Fahrenheit are walked in on, and of course we have Apollo and Midnighter’s introduction. Why do you think this might be?

JAM: I have no idea. It was weird and didn’t seem to serve a purpose beyond telling me: this is an adult book for adults, you see, because look, the adults are doing adult things. On the one hand, sex is absolutely a part of life and we could all probably do with depicting it more healthily and openly—but on the other, all of the sexual relationships seemed to be dead-ends. I don’t know why I care about the fact that green glowy guy and the cowgirl are having sex. I have no idea. My slight guess is that it’s supposed to show that Jackson King is different from Henry Bendix by being lenient with them. Or maybe it’s because he also has a secret relationship with Christine? But then that relationship also seems to be thematically irrelevant. And then there’s Apollo and Midnighter who are so…half-formed. The fact that they’re implied to be sleeping together is good for representation reasons but I have no idea what the story with that relationship is either. Everything is so weird and bad. Stormwatch seems like kind of a bad comic.

Ray: Stormwatch had better written arcs, for sure (I say while having failed to reread them nearly as much as this one). When it comes to “A Finer World,” however, Ellis and Hitch do seem to be doing some very loose form of inquiring about the human condition. The main theme that comes up in all these relationships is secrecy: Jackson and Christine are still keeping their relationship on the down low due to Stormwatch rules, Hellstrike and Farenheit aren’t supposed to be hooking up for the same reasons, and Apollo and Midnighter’s relationship is born while they’re in hiding from Henry Bendix. Also a blink-or-you’ll-miss-it moment: Apollo shushes Stormwatch teammate Stalker when the latter asks him to have breakfast with him after the mission. He only asks Apollo, even though everyone else is there, for a meal that people are known to have after spending the night together. Hm. Wonder what Stormwatch rules those two are trying to dodge there.

It’s hard to find, but the overall message I come away with is that post-Marvel, superhero comics are very concerned about protecting the ones you love through secrecy. Also that it’s unprofessional to get too close to your colleagues when you have a job that requires you to risk your life. On the flip side, it’s human nature to form bonds with people you find yourself in dangerous situations with (just ask Apollo and Midnighter) and this arc seems to wonder what makes a person human. It comes to no obvious conclusion, but that’s my best answer for all the sex.

Heather: I definitely got that ‘This Is An ADULT Book for ADULTS’ vibe from the comic, in regards to all the sex. I also found it a little weird and out of place whenever it was inserted, like it served no real purpose other than to point and say hey look, these superheros are doing it! Like we’re watching a reality show drama unfold. I didn’t feel invested in the majority of the relationships in the book. With the exception of Midnighter and Apollo, who I already knew were going to go on and have a relationship beyond the pages of Stormwatch, everything else seemed to be prety lacking in substance. Even Apollo and Midnighter, without prior knowledge, aren’t developed much beyond a lot of subtext. Maybe this boils down to an excuse to have a lot of sex in the book because you wouldn’t find this stuff in any Justice League comics!

I do buy into the idea of secrecy and the taboo-ness of getting romantically involved with people you work closely with, even if that wasn’t actually the writer’s intent. That sort of plot is always appealing to me, the forbidden love and illicit sex with someone in a high stakes, potentially life or death situation. I like seeing characters be drawn to each other despite regulations and better judgement. It would have been nice to see that conflict reflected more in the text rather than just thrown in every once in awhile for two seconds and left largely up to interpretation.

Before the mission that would prove to change the course of their lives forever, Apollo and Midnighter give up their names and memories of their pre-superpowered lives. This is in contrast to older superheroes such Superman and Batman, who have their alter egos either as disguises or as the genuine other half of their lives. What do you think this choice says about Apollo and Midnighter?

JAM: Once again: Stormwatch is so bad that I couldn’t begin to tell you. I can maybe extrapolate from other similar stories—giving up your name and memories does give me a “will you give yourself to this program” kind of feel. Maybe Apollo and Midnighter are incredibly patriotic/heroic/wanted to do something to help people. (It is interesting that Apollo basically dropped a bomb just outside the White House with absolutely no questions asked. This is a very not-Superman move.) Maybe they were running away from something. Maybe they did something bad and wanted to forget and do something good. Maybe it’s all 3 of those things or something else. The two are shapes of characters in Stormwatch, rather than actual people, so I have absolutely no idea.

Ray: I think it’s less about why Apollo and Midnighter did it as characters and more about what ideas Ellis is toying with by writing in those decisions (let’s be honest, the guy’s strength is not in characters. He largely relies on archetypes and has much more of an interest in exploring concepts rather than people). What he and Hitch ultimately question is, can you still be a person if you don’t have a history or family or identity or even memories? What are you if you’re only who you are in the present moment? Ultimately, based on Apollo and Midnighter desiring nothing more than helping to create a finer world, they suggest that you are still a person through your values and ethics.

Heather: It kind of reminded me of the concept of that Joss Whedon show Dollhouse, and the questions that were raised about what kind of person would willingly sign themselves over to someone else, give up who they were and actually consent to having their entire lives and memories erased, in the interest of being in the service of total strangers. Is it a motivation born out of selflessness or something more selfish? In the case of Midnighter and Apollo: Lack of self-preservation or the innate desire to give yourself over to something bigger than you and help other people? In the case of the ‘dolls’ on that show, a lot of them were treated like subhumans because to the outside viewer, they were basically empty canvases. In Stormwatch not so much, these characters still have clear motivations and while they question what makes them human, I do think it could be making a statement about your beliefs and values keeping you so.

Superheroes with secret identities like Batman and Superman still have their public identities for various reasons—to keep up appearances in the public eye, to protect loved ones who would be in danger if they were directly connected to their alter egos, even to try and hold onto some semblance of a personal life. Sometimes hanging onto their ‘normal life’ can be a way to stay sane, or to not completely become this ‘other person’ they’re constantly balancing, and in other ways it can even serve as a motivation to keep fighting. A lot of that stems from what they have to lose or simply because they believe in doing the right thing, but I agree, the fact that Midnighter and Apollo completely gave up everything and then continued to fight for a better tomorrow even when they didn’t have to anymore, makes them no less human.

While “gay Superman and Batman” comes up a lot, not many people mention it’s because they were initially part of a gay version of the Justice League. More bluntly, however, this is a version of the Justice League set up to question several superhero tropes. What is it to be human? Is it having a name and history? Is it confinement to the basic processes of life, such as eating (as Apollo and Midnighter discuss at the beginning of the arc)? Is it having a sustaining sense of morality? What are Ellis and Hitch trying to ask or imply here?

Heather: Apollo and Midnighter are bio-engineered superhumans, the only survivors of their first mission who go off the grid and then spend five years fighting crime undercover without a mission directive. They miss having their own identities apart from their vigilante personas, they even talk about missing basic bodily functions associated with being ‘normal’, but along with other members of Stormwatch they are living proof that being human isn’t necessarily textbook. Fuji’s body is essentially plasma living inside a specially built containment suit, unable to control his molecular structure outside of it. He doesn’t experience normal physical functions, except for the bizarre way he achieves an orgasm every five minutes. At the end of the day they’re all united under the same values and beliefs of doing the right thing, which has little to do with their biological makeup. Superman is constantly pointed out as an alien, separate from the humans he saves, but he has one of the most unwavering moral centers of any character in the DC universe. Things like names and bodily responses are things associated with being human but I think the desire to be human and to do good is maybe the most human trait of all.

JAM: Oh man. I don’t know? This sounds like a much more interesting and well-put-together comic than the one I read. The note about food was cool and interesting—also headaches—but I don’t feel anything was interrogated in this comic, really. It was all over the place with no/scant thematic centers or reason or anything. Things just happen and there’s a lot of jargon. It’s bad. Ask me again after we read a comic that makes sense.