Here’s the thing: Robin was never intended to be a legacy character. There were no real reasons to assume or suspect that Dick Grayson, the original Robin, was going to give up the mantle. Sure, as Dick progressed in age, thanks to some very specific cultural anxieties, there were reasons to assume that he might get a costume update. But prior to 1982, the idea that anyone but Dick Grayson would ever be calling themselves Robin seriously and for any length of time was pretty far off the radar.

In fact, prior to Jason Todd assuming the mantle of Robin, legacy in the DC canon was largely defined by characters with unrelated powers or skill sets sharing the same name, without direct connection. People like Alan Scott and Hal Jordan were both identified as Green Lantern, but shared completely different power origins. While Al Pratt and Ray Palmer were both known as The Atom, Al was a detective with the ability to use super strength and an “atomic punch” ability, and Ray was a scientist with the ability to shrink to subatomic size. Both Jay Garrick and Barry Allen being the Flash is another example: While both were speedsters, they had no real connection to one another. You get the picture.

The concept of a name and costume being directly handed off from one character to another on the page was not something being widely explored or even considered in DC at the time, especially not by fans. This is important to understand before we start to talk about Jason Todd. Jason is famous for a handful of things. He was the second person to become Robin. He had a temper that may or may not have resulted in the death of a criminal (or several criminals, but we’ll get to that later). He was retconned almost immediately after his first appearance, thanks to the massive continuity reboot event Crisis on Infinite Earths. Oh, and he died by committee, thanks to the results of a call in poll.

That last thing is The Big One. We’ll talk about that more in a moment, since not only is it one of the most famous comic book deaths of our time, and not only has it been elevated to near urban legend status in comic book history, but it also tends to be the only thing people ever want to talk about when it comes to Jason. Let’s zoom out a little bit. Let’s talk about Jason Todd’s life before we talk about his death.

Jason vs. Jason: Pre- and Post-Crisis

Dick Grayson was ousted from the Robin mantle after a forty-four year tenure for a couple reasons. I’ve written pretty extensively about Dick’s history and his transition from Robin to Nightwing already. You can read all about it here. The long and the short of it was that Dick simply outgrew the role of sidekick.

Jason’s original origin story is an alternating saga taking place between Detective Comics and Batman in 1983. He’s first introduced in March with Batman #357 as the trapeze artist child of Joe and Trina Todd, the Flying Todds, of Sloan circus. This incarnation of Jason has red hair and a personality that’s essentially identical to what readers would have remembered from Dick Grayson’s youth, which was obviously the not-so-subtle intention.

In May of 1983, Detective Comics #526 was published as a special 500th anniversary issue, officially placing a newly orphaned Jason into Bruce’s care. The editorial mandate at the time was to introduce a new sidekick for Bruce as quickly and as easily as possible. Jason’s original introduction to the world of masked vigilantism went down like this: he discovers the secret entrance to the Batcave about ten minutes after setting foot into Wayne Manor for the first time. He dons his own ad hoc crime fighting costume, cobbled together from old disguises in a costume trunk belonging to Dick—showcasing his acrobatic chops almost immediately. By the final page of the issue, Bruce and Jason are walking side-by-side into the idyllic grounds of the manor with the pragmatic caption, “But life renews: that is the lesson the Batman and Robin taught each other, years ago. Life renews, with every new dawn.”

While poignant in and of itself, this moment does not address the fact that the name and colors of Robin are still currently in use by the original Boy Wonder. By 1984, Dick was practically a grown man, a college student, and the leader of his own team of superheroes, the Teen Titans. He rarely showed up in Batman books at all, which was becoming a bit of a narrative problem with fans who’d invested in the brand “Batman & Robin,” not “Batman,” solo. This culminated into issue 39 of New Teen Titans. Dick dramatically announces that he is no longer going to be Robin—that Robin is going back to being Batman’s sidekick—and that he is going to craft a new identity for himself, one that can stand alone and independent of Batman and allow him to lead the Titans without caveats.

February of 1984 is a month of pure shared universe continuity magic, with the release of New Teen Titans #39 (Dick “quitting” being Robin), and Batman #368 (Jason Todd officially stepping into the role and donning the costume for the first time) being released almost simultaneously. This provides a convenient solution to the problem posed in the early pages of Batman #368—Jason is offered the sidekick gig by Bruce, but doesn’t feel like he can “steal” Dick’s identity by taking up the name and the costume.

And there you have it, Jason is installed securely beside Batman as the new Robin, and Dick Grayson is Nightwing. A place for everything and everything in it’s place. Except it could never last, not really. Not as idyllically, at least.

The all new, all the same team of Batman and Robin as Bruce Wayne and Jason Todd lasted less than a year before the massive continuity streamlining event, Crisis on Infinite Earths, came through and changed the status of the DC Universe forever. Think of Crisis on Infinite Earths like something of a giant cosmic reset button for the entire DCU, allowing for most characters to be reconstructed from the ground up with histories and backgrounds that carefully hopscotched around the candy-coated absurdity of their torrid 1930s and 1940s pasts.

After Crisis, fans were dropped into a Batman continuity in which Jason Todd had never existed at all. Batman was once again sans Robin, though Dick Grayson was still safely in place as Nightwing. Jason, in all his knock-off glory, had simply never happened. And he would continue to not exist in this new continuity for another year until the publication of Batman #409 in 1987. This is the version of Jason that would stick most clearly in the collective consciousness for a handful of reasons. Namely, this is the Batman story coming hot off the heels of Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One, the story responsible for reestablishing and streamlining Bruce’s origin story in the wake of Crisis. It’s also coming off the recent media attention brought to Batman as a character following another, and arguably more famous story by Miller, The Dark Knight Returns.

The Dark Knight Returns was a pivotal moment in the formation of what we would consider a recognizably “modern” incarnation of Batman, someone who is brooding and dark, a loner who isolates himself from society to obsessively carry out his one man crusade by any brutally violent means necessary. It was also an important milestone for comics a medium when it landed on top of the Young Adult Hardcover New York Times bestsellers list—a feat it only qualified for thanks to its release as a trade paperback in bookstores. For the first time, mainstream audiences were zeroing in on Batman, and not because of a popular TV show or serialized movies, but because of a comic book.

This is the cultural climate the newest variation on Jason Todd is born into, and thus, his new origin story marches to a similarly darker drum beat. This version of Jason is a kid living on the streets of Crime Alley, who Bruce finds attempting to jack the tires off of a parked Batmobile. Rather than punishing young Jason for his attempted crime, Bruce feels endeared to him and his fearlessness, and eventually (in the space of just a handful of issues) takes the young new Jason under his wing to become Robin. Right off the bat, with this new rough-and-tumble origin story and persona, Jason’s relationship with the fans was … complicated at best, and contentious at worst.

A Death In the Family

The event that firmly established the name Jason Todd in the hearts and minds of comic fans spanned across Batman 426-429 (less than 20 issues after Jason’s reintroduction) and was called, aptly, A Death In The Family. In this arc, Jason is manipulated by the Joker into believing that his dead mother is actually alive and working out of the country. Jason sneaks out of Gotham, hops on a plane, and goes globetrotting to follow up on the leads given to him. One such lead genuinely does reunite him with his mother, only for it to be revealed that she is being blackmailed by the Joker and is working to lure Jason into a trap.

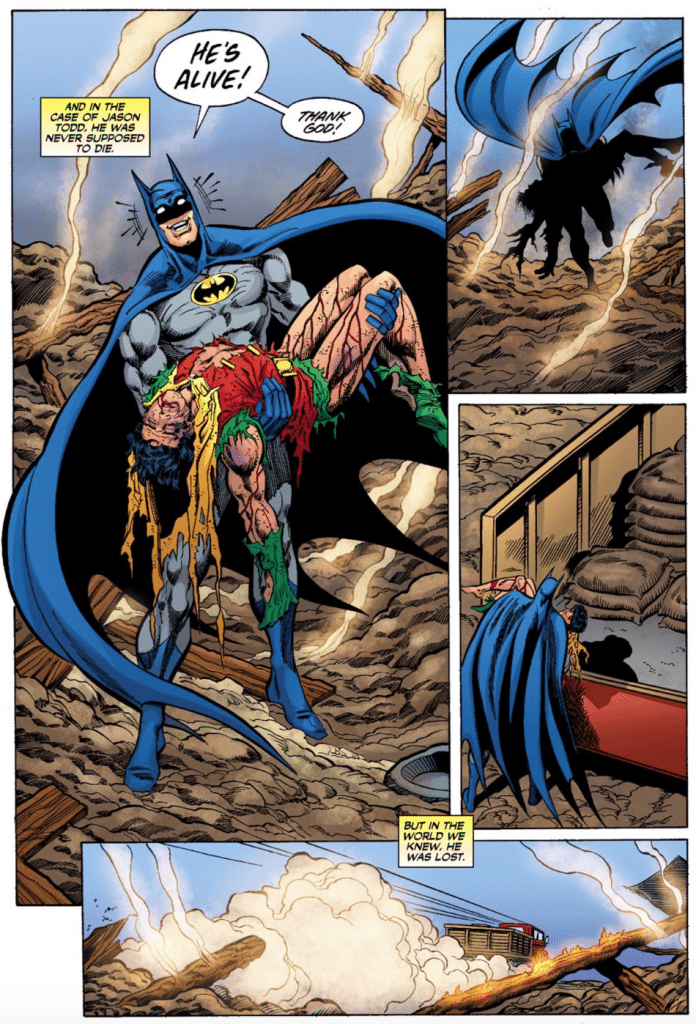

In the arc’s iconic climax, Jason is beaten nearly to death by the Joker with a crowbar and left in a pool of his own blood, trapped with his mother in a warehouse where a ticking time bomb counts down. Too beaten to move or run, Jason is unable to escape from the building, and both he and his mother are killed in the blast. In one of the most famous splash pages in DC comics history, Batman, just moments too late, is shown cradling Jason’s corpse to his chest and screaming in agony.

Horrifying as it was, death itself is not actually the thing that rocketed the event from standard comic book fare to a pop culture media event. It was the manner in which the death was decided. A call-in poll was set up in the back of Batman #428. Two numbers were provided: one to vote for Jason to survive the attack and one for him to die.

The inspiration and origin of the idea varies from story to story, but the most likely origin can be attributed to a combination of sources. Denny O’Neil, the editor of the books, had long been aware of Jason’s lack of popularity with the fans. He looked to the oblique reference of a dead Robin in The Dark Knight Returns as source material for the subsequent mood of the storylines following Jason’s murder. The call-in poll was a concept borrowed from a 1982 episode of Saturday Night Live where the audience was encouraged to call in and vote on the fate of a lobster: Whether it would be cooked and eaten or spared by the end of the episode. O’Neil thought it was a new and exciting way to engage with fans and readers and something to be used on an event with real stakes—“life or death stuff.”

Real stakes, of course, meaning the flat out murder of a teenage boy. The poll remained open for just 36 hours and a total of 10,614 votes were cast, 5,343 in favor of killing the boy and 5,271 in favor of allowing him to live. A difference of just 72 votes set the trajectory for all future Batman comics.

A number of urban legends spiraled out of the poll results, including one about a man who supposedly hated Jason so much he created his own automated calling service to flood the “dead” line with votes. Other stories about editorial regret and childhood heartbreak in which voters on either side lamented their positions steadily cropped up as well. But hindsight, as they say, is 20/20 and the fact of the matter is the fans—conspiracy theories aside—had spoken. Jason Todd was dead. The dynamic duo was no more.

Dead Robins: Killing for Character Development

There are plenty of immediately obvious, in-your-face reasons for why the deliberate and graphic murder of a child on the page is horrifying, even when you set aside the fact that this particular death was brought about by popular vote. The callousness and overt, endemic and contradictory resistance to change/thirst for new things that nerd culture so often represents, for example.

Let’s take a second to unpack where this blood-lust came from. It’d be easiest, and not totally untrue, to say that people didn’t like Jason because he was different. Different and coded in a way that was inherently dissonant to the overarching narrative of the previously held Batman mythology (we’ll talk about this more in a second).

The other half of that equation was the fact that Jason, for all his differences, represented more of the same to Batman fans. The very idea of Robin had been “tainted” by the camp legacy of Burt Ward and the ‘66 TV show, and any pre-Crisis readers still associated the name Jason Todd with the transparent Dick Grayson knock-off who was so shoddily shoe-horned into the narrative just a handful of years prior

In the TV show, Robin’s charm wore thin under a flood of exclamatory puns and gee-wiz boyhood daring-do. This only served as a roadblock for what fans were beginning to consider the “true” Batman stories—that is to say, stories that were dark, hardboiled, and lonely.

It was the perfect storm of too-similar/too-different at the perfect time. The mid-to-late ’80s was the era of people like Alan Moore and Frank Miller crashing into the Batman mythology like freight trains and making things rougher around the edges, grim, and gritty. These new prestige format books allowed for the realization of the “hardboiled,” anti-camp Batman the vocal fans so desired.

While The Dark Knight Returns did make use of the concept of Robin with a new character, a scrappy teenage girl named Carrie Kelley, it took care to remove the idea as far from the baggage of it’s canon incarnations as possible. Carrie’s gender, flaming red hair, and giant futuristic green tinted glasses made her immediately and effortlessly distinguishable from her canonical counterparts. She was an unmistakably new, updated character for a new, updated world. This made her cool to new fans, edgy and yet safe from the baggage of the ghosts of Robins past, a luxury that Jason Todd was never afforded.

Carrie’s existence in The Dark Knight Returns was made possible by the implication of the original Robin being dead in Miller’s bleak new universe. This gave fans one simple justification to kill off a fictional minor: The death of Robin would somehow “help” course correct the Batman universe and make for the level of good, serious, hard hitting drama their appetites had been whetted for.

Even removed from the Miller-ized desire for grim-and-gritty stories, the concepts of Batman and death have been closely linked from the very beginning. In the most reductive sense, Batman is a character that literally embodies the consequence of loss. This was a theme played with now and again by comics of the 50s and 60s that would splash showy, shock value covers with titles like “Robin Dies At Dawn!” over images of Bruce Wayne anguished and carrying Dick Grayson’s body.

But the ’50s and ’60s Silver Age of comics was an era without much in the way of consequence. Robin, obviously, did not actually die at dawn. The plot of that particular book ended up being a ’60s sci-fi flavored dream.

There would be other close calls and hallucinations, moments pushing and testing the ability of the Dark Knight to cope and deal with another traumatic loss on par with that of his parents, but these were never truly viable and never fully realized. The status quo was always maintained, and if Robin was ever actually hurt, he’d recover.

Rinse, wash, repeat.

The opportunity to kill Jason Todd in earnest, no sci-fi dream sequences, no miracle healing, no Scarecrow fear toxin, offered fans a way to break that cycle. Here is one fan’s letter describing their simultaneous respect for Jason coupled with their desire to see him killed, printed in the back of Batman #429:

But there’s another, arguably much more concerning ingredient in the Molotov cocktail that was the anti-Jason, anti-Robin, anti-sidekick fervor that galvanized the comic book community in the wake of Miller and Moore.

Batman, Wealth, and Privilege

Even through the late ’80s reworking, rebooting, and retconning, Batman as a character has managed to maintain a handful of traits, something resembling a cohesive narrative throughout his many incarnations. Most are obvious: Being an orphan and a predominantly nocturnal vigilante, and the surface level iconography of the bat. Other traits are less surface level, like Bruce Wayne’s position of privilege and exorbitant wealth. These have sublimated themselves so intensely into the very fiber of Batman that fans often don’t consider Bruce’s obvious social standing and class to be integral to the character at all.

Bruce Wayne’s transformation from billionaire layabout to something even sort of resembling a philanthropist or activist didn’t actually occur until 1970 when Denny O’Neil removed Bruce from Wayne Manor and shifted the Batman’s base of operations to a closer-to-home penthouse in Gotham City. Prior to this shift in locales, Batman had a decidedly and predominantly high-class focus on his vigilantism. The majority of his crime fighting efforts were zeroed in on rescuing the wealth of the already very wealthy. This, of course, makes sense when you consider his origin as late depression era and World War II style escapist fantasy. Fetishizing and fantasizing about wealth was the vogue of the time and provided a framework for Batman stories that is subtly yet unmistakably classist to modern eyes.

Batman’s oath to wage “war on all criminals” takes a very sinister twist when you can parse out the definition of “criminal” as “poor people.” This classism and fear of the poor begins to fade in comic narratives thanks to the influence of ’60s camp and pop art appropriation of comic iconography. The overarching assumption that crime in Gotham is largely conducted by the underprivileged with the goal of victimizing the wealthy doesn’t start to change until the mid to late ’70s. Even then, the shift is gradual at best.

Unsurprisingly, the late ’60s and ’70s were also the dawning of the collectible comic era, a period of time when the widely accepted “junk art” of comic books were just starting to be seen as something worth holding on to. This was largely in part because the children who had been the sole audience for comics at their genesis in the ’30s and ’40s had become adults with kids of their own. The idea of saving comics to pass along to generations or to keep in pristine condition for themselves for the sake of nostalgia was really beginning to take root. The collector boom would happen definitively in the mid ’80s. Comics would complete their transformation from “low brow” art form marketed toward the disenfranchised lower classes and kids looking for escapism to a potentially valuable commodity marketed towards middle class men with disposable income and the obsessive need to gather things like variant covers.

So you can see why there would be a discomfort among fans—even on a totally subconscious level—at the idea of a Robin who is overtly and unrepentantly introduced as not only a definitively lower class kid, but also a literal criminal. The idea is almost paradoxical, even to readers who are new to the Batman mythology thanks to their exposure to The Dark Knight Returns or The Killing Joke. Batman is a character who fundamentally opposes criminals in the most explicit and literal way. Batman is also a character that exemplifies wealth and the luxury that wealth affords. Why then should we the fans buy the idea of this street urchin being rewarded for breaking the law?

Add to this the contingent of purist fans who were still galvanized at the mere thought of someone other than Dick Grayson stepping into the role of Robin—a character that until just recently was assumed to be as static and solid in his own cape and pixie boots as Bruce Wayne was in his cowl—and you have a recipe for some pretty vocal backlash.

This also comes at a time where the Batman and Robin partnership was being framed as anything but dynamic for the first time. Post Crisis on Infinite Earths, even Dick Grayson’s relationship with his mentor went from amicable split to toxic firing and estrangement. This was even further illustrated in Batman #416, in which Dick and Jason meet for the first time post Crisis. Rather than the friendly passing-of-the-torch that occurred between the two young men in the pre-Crisis universe, this new post-Crisis world has Dick being both shocked and hurt that Bruce would have chosen to replace him and illustrates a divide between the two characters which was never there before.

Post-Crisis Dick and Bruce were barely even on speaking terms when Jason assumed the mantle, and Jason was given no knowledge of the former Boy Wonder from Bruce—total about-face from the previously established sequence of events.

Jason Todd and Bruce Wayne were two characters who obviously grated against one another: A Robin who bristled at Batman’s authority and a Batman who questioned his ability to trust his own partner. This was the influence of the grim-and-gritty world of Frank Miller and Alan Moore coming to it’s most logical conclusion in the main continuity of the DC universe. This was an era that desperately wanted to lean into concepts like dysfunction and violent youth culture. If Batman comics were a living breathing thing, the late ’80s and early ’90s were, in an almost literal sense, the start of their “You don’t understand me, dad!” teenage years.

Jason’s rocky start as the post-Crisis Robin only got rockier as fan backlash increases, creating a sort of feedback loop of action and reaction between writers and fans. The more the fans protested, the brattier and less likable Jason became. It didn’t take long before we had Jason displaying shows of excessive force and bullheadedness that concern even Batman himself.

The most dramatic of these violent outbursts occurs in Batman #424 when Jason, semi-ambiguously, allows a rapist to fall to their death. The fallout of this action reverberates through the next several issues. The writers at the time didn’t know it yet, but this would be Jason’s penultimate story arc as the Boy Wonder—the feather that would serve to topple the already teetering tower of fan concerns, doubts, and resentment about the need for a teen sidekick in the Batman narrative at all.

Now you’d think that in this anti-camp, extra toughened fan climate that readers would have felt a thrill at the idea of a Robin so willing to transgress against Batman’s staunch, often frustrating moral code. But not, apparently, when said Robin is a former street kid with a predisposition for law breaking.

Brutality, and the disregard of moral absolutes, was only cool when Bruce himself did it, and not some kid, and especially not some kid from the Narrows of Gotham. Jason was a brat rather than a “badass,” a baggage-laden thorn in the side rather than a cool, edgy new interpretation of a sidekick. He simultaneously was a crook who besmirched the good name and reputation of a childhood hero and a garish reminder of the technicolor pop-candy history of a now gritty Dark Knight. But more than anything else, he was an outsider to the narrative of Batman’s fundamentally exclusionary and isolating wealth and social class. He paid for it with his life.

Aftermath: 1989 to 2005

Following A Death in The Family, Bruce was shown dealing with Jason’s death by explicitly not dealing with it, or dealing very, very poorly. The most immediate reaction moment came in the form of The New Titans #55 published in June of 1989, when Dick Grayson learns about Jason after having been off planet for several weeks. The encounter is … unpleasant and admittedly exactly what voters were looking for.

Batman #436, published August 1989, featured more examination of the Batcave and Wayne Manor by Dick who notes that Bruce has, rather unsurprisingly, gone to great lengths to erase any trace of Jason’s life with him.

Eventually, the glass display case that housed the Robin uniform began to be considered a memorial for Jason Todd rather than just a costume storage piece. It became one of the most notable and permanent set pieces of the cave, next to the giant copper penny or animatronic dinosaur.

This grieving eventually culminated into a Batman and New Titans cross over event called A Lonely Place of Dying (beginning October 1989), which had the express purpose of filling the role of Robin once more. A new character, Tim Drake, was introduced to take the job. He was given an origin story that directly tied to a noticeable uptick in brutal, dangerous behavior by Batman, spurred on by—what Tim assumed—was the lack of a sidekick.

“Batman needs a Robin,” young Tim Drake noted. And he was right. After 30-some years of narrative synergy, the dynamic duo were as interwoven with one another as they could be. An empty Robin costume simply wouldn’t do for very long, no matter how desperately fans wanted to shun the concept of a kid sidekick tagging along with their brooding Gothic hero. Also, Tim Burton had just released a movie and a sequel was in the works, and more marketable characters meant more merchandising. You get the idea.

To really get a grasp on just how maligned the concept of Robin and Jason Todd had become by 1989, take a look at the introductory essay before the 1991 publication of the Robin: A Hero Reborn trade paperback. The essay, written by Chuck Dixon—the man largely credited with laying the groundwork for our modern interpretation of not only Robin, but Nightwing as well—goes to some length to establish just how disinterested and even annoyed with the Boy Wonder fans had become.

Dixon writes, “Jason did not click as Robin. Reaction to him was negative all the way around. When the Joker did him in, there weren’t too many mourners.”

Sidenote: There were some mourners! While the reaction to Jason was largely negative, he did have fans. Rather famously, an eight-year-old girl wrote into the letters column to confess having cried “for a whole day” after Jason perished. The editorial response was a pretty troubling case of victim blaming:

The next 16 years of Batman stories would be subtly haunted by Jason Todd’s ghost. His death closed the circle of Bruce’s origin story, transforming him from orphaned son to grieving father.

The ’90s, in all their cartoonish extremes, went through a phase of absolute gleefully killing of established heroes and replacing them with younger, newer versions of themselves. In this way, Jason’s death was both an incendiary incident and complete outlier. He’s arguably one of the first casualties of this great purge but simultaneously something completely apart from it.

Jason’s death was not intended to be making room for a newer, hipper, more extreme Robin the way that say, Hal Jordan’s death was designed to make room for Kyle Rayner, or Green Arrow’s death was meant to lead to an adoption of the mantle by Connor Hawke. But it would be impossible to pretend the success and attention garnered by Jason’s death didn’t in any way influence this morbid trend in the years following its publication.

Despite the almost immediate introduction of a new Robin, Jason’s death was largely accepted by fans to be a tragic but ultimately worthwhile endeavor, something that belonged securely on a short but important list of widely accepted formative events in Bruce Wayne’s life and career. The murder of his parents, the guardianship of Dick Grayson, taking the oath to war on all criminals, and the death of Jason Todd—these were things that made Batman, Batman.

Over time, the glass trophy case of the empty Robin uniform became a sort of artistic shorthand for angst and brooding, a quick and easy way to signal to readers in the know that Bruce—or any member of the Batfamily—was considering something heavy and grave.

Jason’s death became so quickly and strongly entrenched in Batman canon that editor Denny O’Neil allowed himself to go on record saying, “It would be a really sleazy stunt to bring him back,” a quote that would go on to be printed on the back cover of the first printings of the Death in the Family trade paperback.

Make no mistake though, as far as on-panel grieving was concerned, there wasn’t much. This was the ’90s, a decade in comics fraught with over the top machismo, flaming wrist daggers, laser guns, ponytails, and so, so many belt pouches. By the time Tim Drake had taken up the cape and pixie boots, the stories spent making explicit reference to Jason declined dramatically, relegated to issues revolving around flashbacks, like Legends of the Dark Knight #100, published in 1997, which retells both Dick Grayson’s origin story and Jason’s first and last days as Robin. Jason’s death, like the death of Bruce Wayne’s parents, served as a meaningful, but only whispered about plot point lurking in the background of story arcs, to be pulled out when writers needed a conveniently poignant and sober moment of self-reflection or loathing for the Dark Knight and his allies.

The ’90s also brought about some of the biggest and most landscape-altering crossover plotlines in Gotham City history—events like Contagion, Zero Hour, Cataclysm, and No Man’s Land encompassed nearly all of the page space for years at a time. So it’s easy to see how and why Jason’s restless ghost didn’t start becoming a major focal point of Bat-plots again until the early and mid 2000s, when the mood of comics was finally beginning to shy away from the EXTREME landscape of the ’90s action and overblown machismo.

This was the dawning of a new era in comics, largely sparked by the paranoia and introspection brought about by national tragedies like 9/11 and ongoing international conflicts like the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Suddenly superhero stories were less interested in punching contests and cartoonishly exaggerated muscles and more focused on introspection and really unpacking the morally ambiguous landscapes that vigilantes—even ones considered to be wholly Good Guys—operated in. This was the era of DC events like Identity Crisis and Bruce Wayne: Murderer/Fugitive, stories that aggressively sought to drag the murk and mire of the superhero into the open and challenge their accountability, necessity, and ability to rally against foes that weren’t villains in brightly colored costumes. This was also the era of Jason Todd’s resurgence from relative obscurity to the limelight.

By 2002, Jason’s memory was made a critical part of story arcs once again. The famous Jim Lee/Jeff Loeb story, Hush, featured the first non-flashback appearance of Jason since his death, with Clayface impersonating him to drive Batman further over the edge. This was part of a scheme concocted with the express purpose of unraveling both Bruce Wayne and Batman’s lives simultaneously.

In 2003, a three-issue arc of Gotham Knights featured a story about child services investigating Bruce Wayne, dealing with the fact that Jason’s disappearance and death was actually a legal matter that, realistically, would have had to have been dealt with outside the world of capes and cowls.

This story arc also employs some revisionist history, with writer Scott Beatty using flashbacks to introduce even rougher edges to Jason prior to his death. Tiny details, like Jason being an under-aged smoker, only served to add to the miasma of danger surrounding him. Adding in a friendly relationship with Barbara Gordon, Batgirl at the time, served to up the emotional ante of his death.

In the Infinite Crisis event of 2006, Bruce is shown having what amounts to a panic attack and remembering the traumatic events of his life: His parents death, and Jason’s death chief among them.

But cameo appearances and an introspective narrative focus were just the beginning. Remember how Denny O’Neil said it would be a “sleazy stunt” to bring Jason back? Guess what happened next?

Under the Hood: 2005 and Beyond

Death in comic books is rarely a permanent condition. Since the aptly named Death and Return of Superman in 1993, the DC universe has been a place where no one stays buried for too long. So, by today’s standards, Jason’s staying dead for 16 years was an almost Herculean feat.

The road to his resurrection was … complicated, as comics often are. It involved the literal punching of reality by an alternate universe version of Superboy. No, I’m not joking. Superboy Prime punched reality so hard he brought Jason Todd back to life. But let’s not dwell too long on that. Trust me.

In 2005, Writer Judd Winick begins an arc called, rather nondescriptly, Under the Hood, shortly after the completion of the War Games. That event saw the death of yet another former Robin, Stephanie Brown, and instated the insane Black Mask as the new ruler of Gotham’s underground. The stage is set: A city torn asunder by both the events of War Games and of the massive cross title event Infinite Crisis, which caused some major shifts in the status quo.

In short, Under the Hood begins in a pretty tumultuous time as far as continuity is concerned. It also zeroes in on some particular breadcrumbs dropped in the Hush storyline, namely that Clayface was impersonating an adult version of Jason Todd rather than the remembered version. The idea that Clayface was working from a reference of some kind to base his version of adult Jason was an idea never fully explored in Hush and something that Winick cleverly capitalizes on.

Under the Hood tells the story of a new crime lord surfacing in Gotham using the moniker “Red Hood,” a name intentionally lifted from a widely accepted Joker origin story. Red Hood takes the Gotham underground by storm, working his way up the chain of command until he’s contending with the recently installed top dog Black Mask and shamelessly gunning for Batman’s attention.

In a twist of events that’s hardly a twist at all, Red Hood is revealed to be none other than a resurrected Jason Todd come to dredge up the ghosts of Bruce’s past and seek (kind of justifiable) vengeance on the Dark Knight for his own demise. It turns out that shortly after Superboy Prime’s reality-altering punch, Jason was able to crawl out of his own grave in a near brain dead state. He was found and taken in by a hospital as a John Doe before being turned out on the street. It’s there he’s found by a handful of League of Assassins thugs who then deliver him into the arms of Talia Al-Ghul, daughter of long-time Bat-nemesis, Ra’s Al-Ghul.

If this sounds pretty convoluted and confusing, it kind of is. Make no mistake, bringing a character back from the dead, though common in comics, is rarely a simple task. The long and the short of Under the Hood is this: Jason Todd is back, Jason Todd is furious, and Jason Todd wants revenge on the people he holds responsible for his death.

Those people being The Joker, obviously, and Batman himself, though not for not saving his life but for allowing the Joker to live and continue to hurt people. Also, in a rather strange and metatextual way, the readers themselves were being looked at with an accusatory eye. After all, it was the readers who were the final say in Jason’s demise, something Winick explicitly calls out in a moment discussing the strange circumstances around Jason’s revival.

He was never supposed to die, Winick posits, but he did. And now we all have to deal with the consequences. Except this is where the second layer of true subversiveness begins to form in Under the Hood. Rather than simply allowing us to write Jason off as a murderous villain—even though he is literally murderous and literally a villain at this point in the narrative—Winick leans into the idea of Jason as victim and devotes entire issues to the exploration of just how failed and abandoned he was, not by only the system, but by his family (biological and adoptive) as well.

By doing this, Winick turns the notion of the “almost criminal” Robin that had concerned so many readers in the late ’80s on its head. Jason died because, as a child, he showed the potential to become a criminal, a murderer, to shirk Batman’s teachings and rebel against the Dark Knight’s authority in disastrous ways. Now, nearly two decades later, all of those anxieties have been realized in the most literal sense they could be, and that’s what makes the newly returned Jason Todd so damned, and undeniably, engaging.

And in one final, incredibly subtle narrative stroke, Winick gave a nod to Jason’s initial status as one of the original legacy adopters of the DCU by giving him what essentially amounted to a corrupted legacy title as the Red Hood. Like I mentioned before, the name was adopted from a widely accepted Joker origin story—this is something that is explicitly called out in the text. It’s an intentional call back.

In claiming this name, Jason is stepping into the mantle of the man who killed him and twisting it into his own image. He’s, in an almost literal sense, reclaiming his own death from both the Joker himself and from the fans responsible for it. His legacy status, now a corrupted and perverted image of itself, is maintained and weaponized in a totally new and unexpected way.

None of this is to say that Under the Hood was well regarded as it was released. The reality is that the story arc tapped into a specific subset of new Batman fans, many of whom only became familiar with it after it was published as a collected trade paperback. While critics and many long time readers roiled at the broken promise of Jason staying dead, new fans who may have been previously unfamiliar with the idea of Jason Todd at all flocked to this new face on the Gotham streets.

Regardless of the backlash at the very idea of reviving a character sworn to stay dead, Jason’s popularity soon took root. Under the Hood rapidly became an accessible entry point for new readers to jump into the densely complicated world of Batman comics and continuity.

By 2006, the culture of fans that had condemned Jason to death for his difference and his edge was now reveling in it. The same climate that had produced stories like Identity Crisis and War Games, which were all about questioning the need and morality of superheroes, was now taking readers’ interests to the next logical step: Exalting a former pariah, a character that existed to, in no short order, explicitly and definitively rally against the very idea of the Batman, to expose the logical fallacy and shortcomings of his mission.

If the good versus bad/black versus white/day versus night moral binary of the superhero world was teetering on the edge of irrelevance at the dawning of the new millennium, the undeniable success of Under The Hood shoved it off and lit some fireworks to celebrate.

An aside/addendum to Jason’s popularity, at risk of sounding completely reductive for a second: Red Hood is hot.

It’s up for debate how much his appearance may have helped him gain the initial traction needed to start to snowball like he did, but it certainly didn’t hurt. And, in many ways, Jason filled the same visual niche as his “big brother,” Dick Grayson—which is to say, an idealized, but decidedly different iteration of the hyper-masculine male hero body.

By the early 2000s, this particular niche was not expressly lacking in the DCU at large, but in Gotham City the male character roster typically ranged from the cartoonishly macho “traditional” superhero like Batman and Azrael, plucky decidedly adolescent teens like Tim Drake, and the grotesque array of super villains. Nightwing, famously, stood apart from his counterparts as a sex symbol for his ability to use the standardized superhero physique and prowess in a way far more palatable to those who were looking for it.

Jason’s new adult incarnation provided a much needed equal-yet-opposite alternative to Dick Grayson’s complex and baggage-laden status in the Bat-family canon. Jason’s childhood was cut too short to gain any degree of metatextual and subtextual anxiety, and he actively embraced his dangerous, decidedly tarnished status as a villain-turned-antihero.

Red Hood is, in basically every way, the anti-Nightwing. The prodigal son who never came home. The good soldier turned bad. The problem child rather than the golden boy. And this amalgamation of tropes sells, especially when wrapped in a leather clad, gun strapped, fit, and classically handsome package.

For the first time ever, fans of Batman were not only being encouraged to empathize and root for a character explicitly in opposition to the Batman code and oath, but a character that was all but served up on a sleek, sexy silver platter. The perfect storm of rebel-with-a-cause edge and intrigue with a built in history rife with all kinds of dark and stormy nooks and crannies to be explored and expounded upon.

Under the Hood saw to it that Jason Todd was not only back, but better and more popular than ever. Take that, call in poll results.

Into The Present

It’s decidedly passed the statute of limitations on spoilers, so I’m going to go ahead and tell you: The ending of Under the Hood does not tie a nice little bow around Jason’s story. It does not magically repair his relationship with the rest of the Bat-family, nor does it actively try to redeem any of his choices. Rather, it ends on a note that is, unsurprisingly, pretty ambiguous. And because the nature of the beast in mainstream comics is a shared universe, this ambiguity was largely left to splash over into other books with other characters.

Jason began to crop up in other titles to act as a chaotic force—sometimes written by Winick, sometimes by others—and something interesting began to happen. People began to vehemently disagree on who, and what, Jason was supposed to be in the scope of whatever narrative he was in. The idea of “ownership” of a character in geek communities was not at all new, nor was it something specific or endemic to Jason, but the fact that his reintroduction was mired in such deliberate moral gray only served to feed the voices of fans, both new and old. Jason rapidly became an incredibly contested feature of not just Gotham City, but the DCU at large.

In the years after his return, Jason became a sort of Rorschach test for both fans and creators. He would transmute from tortured, sympathetic foil to criminally insane mastermind and back again based on seemingly nothing more than the context of whatever story he was in. Under Winick, the Red Hood was a scary yet redeemable, misguided, and undeniably messed up kid. To then Teen Titans scribe Geoff Johns, he was a murderous sociopath undergoing a massive identity crisis. To Paul Dini and Sean McKeever, he was a begrudgingly heroic hothead. To Tony Daniel, he was a psychotic wrapped in a suit of armor that looked like a cross between a death metal front man and a renaissance knight.

In the New 52 reboot of the DC continuity, Jason takes the form of team leader and title character of an ongoing series that positions him as a rough-around-the-edges mercenary for hire with a background in mystical and spiritual martial arts. Soon, in the new DC soft-reboot of the New 52 universe, he’ll be the “evil” Batman counterpart in a dark Trinity team made up of Bizarro and Artemis the Amazon.

In short, no one has ever really been sure what to do with Jason, or where to go with him. He does not have the baggage of a character like Dick Grayson, but he comes with his own set of complexities. In a way, his rebirth into Red Hood and lack of a clear redemptive arc made good on the classist assumption of the ’80s that Jason’s lower class roots made somehow more predisposed to being a fully realized criminal. In another way, Jason’s lack of a clear moral code and path made him appealing and dynamic in the starkly binary world of Gotham City.

His existence was founded upon and perpetuated by the idea of existing in an in between state. As Robin, he existed both in the world of the wealth and class afforded by Wayne Manor and the poverty-stricken world of the Narrows. As Red Hood, he works in the liminal state between Batman and his allies’ strict moral code and his own need to exact extreme and absolute justice. In an almost literal sense, he is in between life and death. This is what makes him work. The difficulty fans and creators have in parsing him into any concrete category is by design, the spine to which his narrative is grafted.

Complexities and wildly varying portrayals aside, one thing was certain: Under the Hood grew from much maligned frustration for old school Bat-fans to exalted and wildly hailed definitive text by a newly organized fanbase. Since it’s release as a comic, Under the Hood has become one of the most retold stories in the Batman canon. It’s taken the form of animated feature film, the backbone plot to a major Batman video game, and now has persistently circulating rumors of a live action adaptation coming in the near future.

This staying power is not by accident. Jason Todd represents the sort of clunky elegance and magnetism that is the trial and error phase of comics history. He came into existence as part of a shift that would change the way DC would grow to define their relationship with legacy and on the cusp of an event that would radically morph the entire universe’s continuity. He provided a gateway into the intimidating world of Batman comics for newcomers, became a sex symbol for a niche of fans who were largely being ignored prior to his resurrection, and blazed a trail that would become the primer for the Robin mantle and it’s future bearers. His history is a tumultuous, complicated, topsy turvy cross section of classist anxiety, ingrained fear of difference, and false starts that grew into an exaltation of everything Batman comics once vehemently rejected. His ability to adapt and reflect makes him both occasionally contested, vehemently prized, and unarguably timeless.

Love him or hate him, Jason Todd is here to stay.

I am old 🙂 I was one of the people who voted. Now, I HATED the reboot hubcap thieving little creep, but I felt he was written so we’d not like him. I was disappointed with with the pre-crisis kid, like most people, since he was a red-headed Dick. In part, this was lazy writing (all due respect guys, but come on). I thought making him dye his red hair brown was ridiculous. Robin, despite the Peter Pan slippers was clearly being written and a young adult. People will notice he is younger, you are fooling no one, let him keep his hair.

I was dead broke, working my way through college, but I voted. My first job was at a comic book store, making me an OG fan girl, I guess, and I encouraged people to vote to save him. I don’t recall anyone saying, "nope, let the PIA die, and bring back Dick, making Nightwing his new partner. Because killing a teen, in a role kids are supposed to identify with, that was just sick. And I could see several narrative options to calm him and make him more of a pro. And people forget, Bruce ADOPTED Jason, and never did Dick.

But after he died I thought–ok, you murdered a young boy. Don’t undercut it by bringing him back. But when I say "Jason" in Hush I found myself happy, and digging the white flare of hair (bring it back). I think he has become dynamic, interesting, and regaining his grip. Don’t forget, many who come out of a pit are unhinged for a while. Jason got rehinged. I liked him with Roy. Jason was the first killed; Roy was the first to fall from grace because of his heroin addiction and thrown out, not helped. I thought they were good partners (not Starfire–her depiction as a ditz who does remember being a Titan or loving Dick while wearing highly impractical "armor" just sucked.

I like his new team. Artemis has finally become interesting and this is my favorite Bizzato yet–and the way Jason takes care of him in the clearest indication of his good news.

DC has been trying to make him an anti-hero, and I think this does it. And I am glad he wears an old costume of Dick’s and wears the Bat. Now if we could get that darn cap of Roy in Titans, I can die happy!

4.5

This was very cool. 🙂

Amazing article. Gave me really good insight about the character and furthermore, about the history of my favorite comic book brand. Thanks for taing the time to research and put together such a fantastic read.

That was some of the best writing about a character (addressing both its own internal and contextual history) that I’ve ever read.

A fantastic article.

This is really excellent work. Every single DC writer who tackles Jason Todd should be sat down and made to read this – maybe then they would understand why Jason Todd matters so much to so many people.

It’s kind of sad that Jason Todd has more or less gone in a full circle with the New 52, he’s back to being a knockoff character with no one really likes. In the past five years, he’s pretty much been a self-insert character for a sexist writer working for an editor who repeatedly harasses women.

Wonderful article! Will read again for sure. Thank you for writing!

This is sooo great!!