Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes plays around with a lot of snow. Snowballs, snowmen, snow forts—snow, snow, snow. It is used as both a plot device and a background in many different ways—never sentimental or sappy. Let’s take a look at the main functions of snow for Calvin: Mischief, Artistry, Philosophizing, and Fantasy.

Mischief

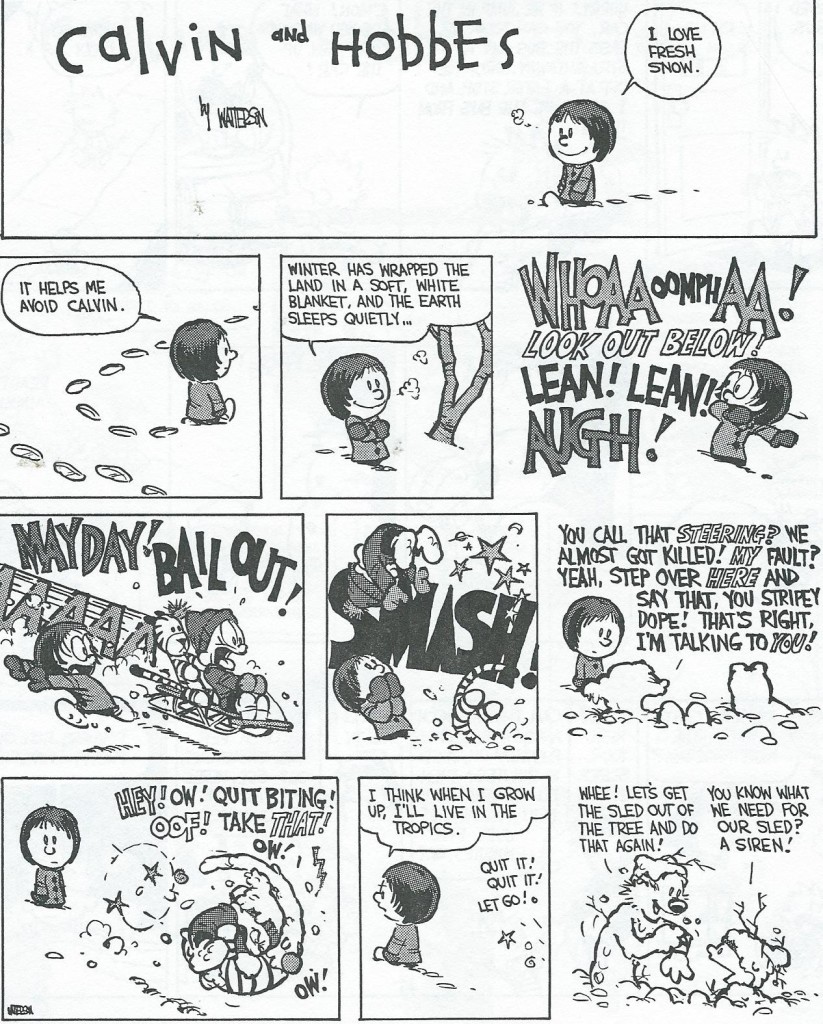

Starting with Mischief as our first category, Calvin’s tricks are mainly inflicted on Hobbes, Susie, his Dad, and, to a lesser degree, his Mom. Calvin and Hobbes constantly throw snowballs at each other, but with different approaches. Calvin often hatches elaborate plans that prove overly complicated (such as building a decoy snowman on their front stoop, dressing it in his clothes, then getting locked outside in his underwear), while Hobbes’ tactic is of brute strength (such as rolling up a giant snowball and then jamming Calvin into it head first). The two are not always on attack-mode though. They build and plot together, as well as playing Speed Sled Base Snow Ball (Winter’s answer to Summer’s Calvinball). They engage in shared mischief as well as ambushing each other, which contrasts from his relationships with other the characters.

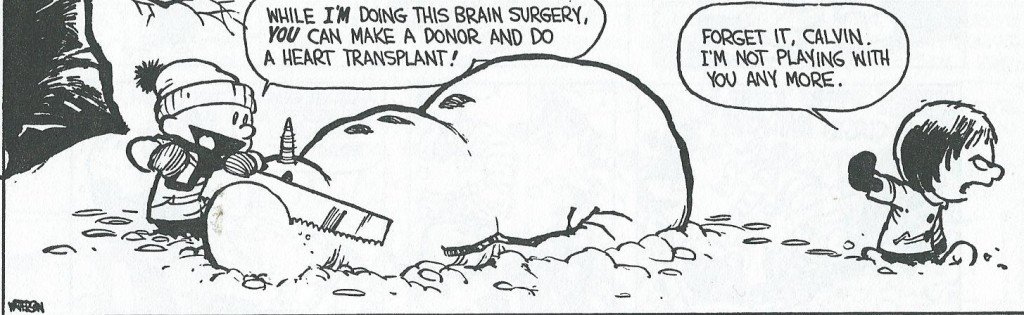

Calvin’s favorite target is difficult to detect, as he pulls stunts on Susie and his Dad with equal tenacity. He devises dozens of plans to pelt Susie with snowballs, most of which end with him missing followed by her retaliation, as well as the occasional apology. The two never play in the snow cooperatively, save for one short-lived instance where they built a snowman laying on the ground which Calvin began performing brain surgery on. Calvin even struggles with the moral implications of whether or not he is a bad person based on how much he enjoys hitting Susie with snowballs. He theorizes how Santa might interpret his behavior, and his self-awareness over this struggle actually taints his enjoyment of the whole scene. But he can’t resist the temptation to make physical contact with her. Young love!

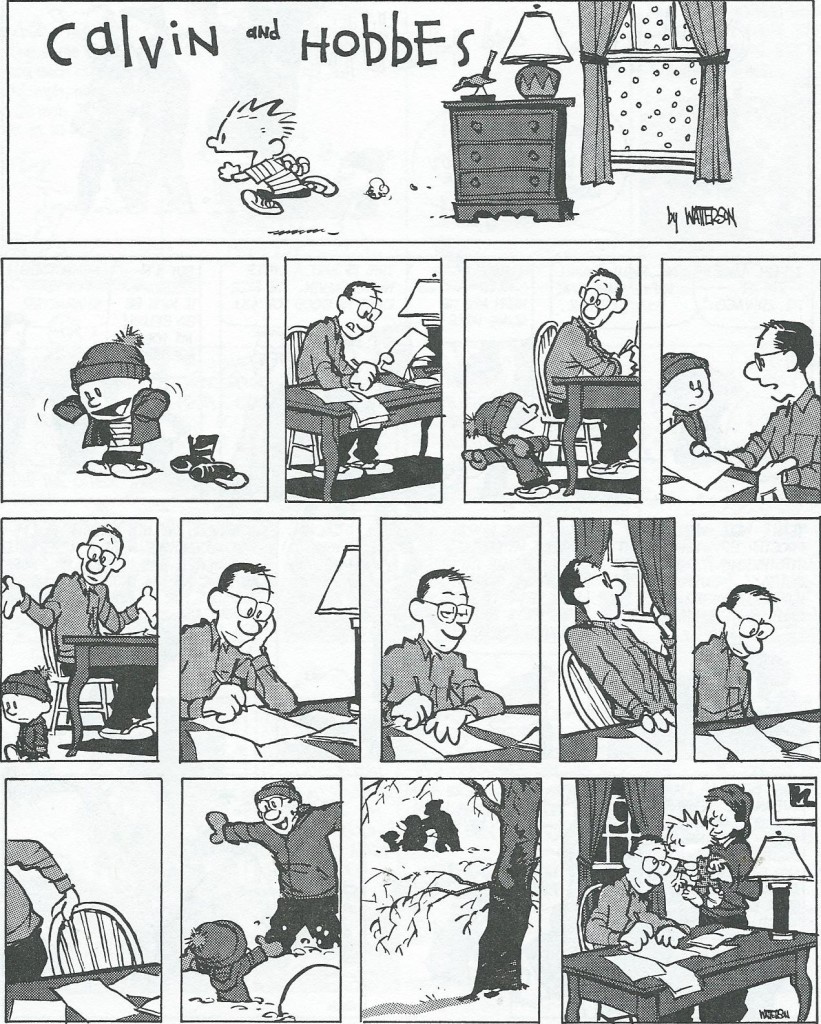

For this reason, I believe that his dad is actually his favorite target. Calvin never grapples with the morality of tripping up his dad with the snow. He’s never shown devising his snow-schemes against him, but the extent and number of times it occurs gives insight into his level of enjoyment. While he doesn’t regularly throw snowballs at his dad, Calvin comes up with various obstacles to stop him from leaving the house. His path from the front door to the car is blocked by maze-like shoveled pathways, large piles of snow is placed in front of the garage, and a highly populated snowman crossing constructed across the driveway; it’s like Calvin doesn’t want his dad to leave. He wants to engage with him, and does so through provoking him with snow pranks. Without expressing emotion or communicating verbally, Calvin manipulates his surroundings to connect with people. Notice that there are never barriers blocking his dad from returning home.

In one case, there is actually a row of snowmen saluting him along the path to the door. In fact, one of the few strips that touches on the sweetness of their relationship is set in the winter. In a wordless Sunday comic, Calvin asks his dad to play outside, his dad says no, then leaves his work to play outside after all. In the final panel, Calvin gives his dad a kiss goodnight with a little heart between them. The snow mischief functions as a means to give Calvin what he wants: attention.

Calvin and his mom have a close relationship. They have similar personalities in many ways, and he receives plenty of attention from her. It is not necessary for him to throw snowballs at her to instigate a connection, plus she clearly hates cold weather. She is rarely outside in the cold and is instead depicted in front of the fireplace, annoyed at the dad raving about how great the cold is, and drinking mugs of coffee and hot chocolate. But Calvin does bring the winter inside to her. In three different strips, he leaves a door open for a comical amount of time, letting wind and snow accumulate inside the house. There is strip where he goes so far as building a snowman with the snow that blew indoors. He also tries to trick her with snow, planting a snow-Calvin decoy in the tub to avoid his bath. There is one solitary incident where he hits both parents with snowballs inside the house, which is never shown happening again. He never torments her with snow, but he manages to get her a little bit, which is basically his way of saying he loves her.

While the snow mischief is a method to facilitate bonding between friends and family, Calvin also creates a series of sadistic sculptures visible to their neighborhood. Hints that their neighbors are none too happy are sprinkled throughout the series, from Susie indicating nobody has bought a house on their street in years to his dad saying, “You have to admit it’s slowed down the traffic on our road.” And this brings us to our next topic: Artistry.

Artistry

Calvin experiments with the snow, sometimes using it as a tool for self expression, other times as a reaction to the art scene itself. His art varies between the abstract (“The Torment of Existence Weighed Against the Horror of Nonbeing’” anyone?) to kitsch, with him explaining his works to Hobbes each time.

In one instance, he leads Hobbes to a field of freshly fallen snow and says “Art is dead.” His new piece is the untouched canvas and signs his name to it with a stick. Even snowballs are a reflection of Calvin the Artist: “When I make a snowball, it’s a work of art!” The art is always done by Calvin alone without any collaboration, save for the one time he invited Hobbes to help him complete his piece on “compromise,” which obviously ended badly for everyone involved. There is also a small piece where Hobbes is sculpting a statue of Calvin; even in the one instance where another character makes a snow sculpture, it is Calvin in essence. While creating art is not an inherently narcissistic activity, in Calvin’s case it is definitely an arena for his egoism. In There’s Treasure Everywhere he says, “It’s tough being the sole guardian of high culture,” and “It takes a genius like me to create art” in Scientific Progress Goes “Boink.”

His egoism is not limited to his own pieces, and gets even worse when critiquing other kids’ work. Standard snowmen are not considered art; they must be either part of a scene (i.e. the snowman representing the spirit of the new year) or a commentary on how typical they are. He does enter a brief creative phase where he dabbles in nostalgic snowmen (i.e. the “Bourgeois Buffoon”), but he does so ironically. Calvin never presents his sadistic snowmen as art, which is fitting as their main purpose is for mischief rather than self-expression.

Philosophizing

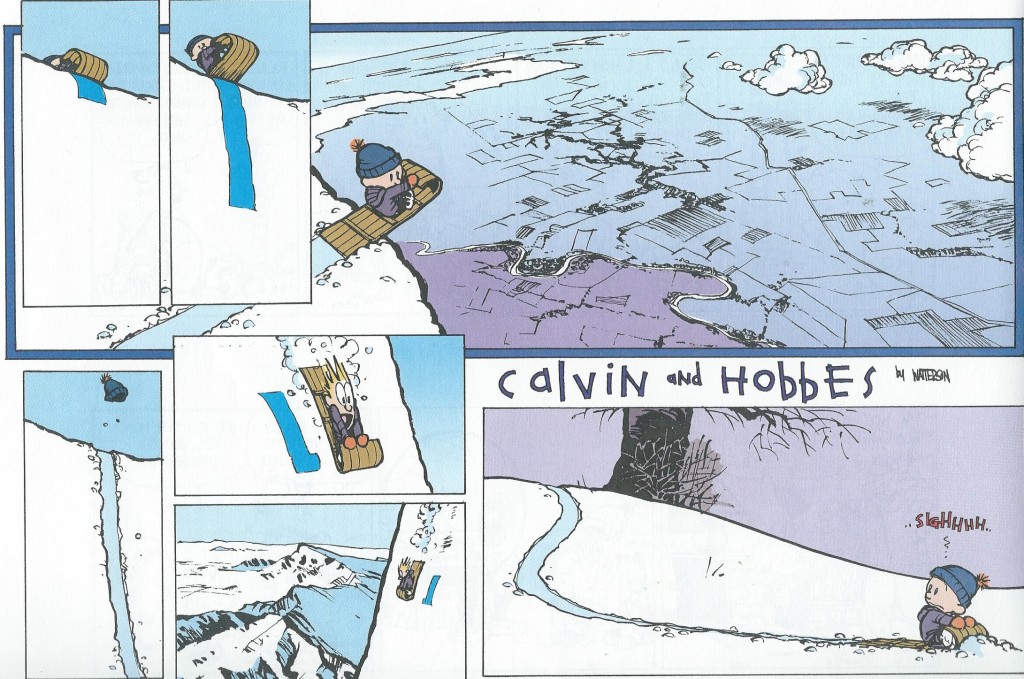

On the flipside of his snow sculpture fueled narcissism are Calvin’s quiet walks and toboggan rides. Calvin and Hobbes occasionally go for long walks and hold intense conversations about the meaning of life. Meanwhile, the sled ride is the winterized version of the wagon rides of the Summer, and these scenes are used as a stage for philosophizing. Calvin seizes these opportunities to reflect on issues of life and death, with Hobbes as his captive audience. Usually these sled rides are death defying and Hobbes isn’t give much time to formulate responses; it is primarily Calvin performing intellectual monologues for his terrified friend. These one-sided discussions cover a wide range of topics: that change is the essence of life; the possibility of reincarnation; how their toboggan ride would be made significant by being viewed and vicariously experienced by others rather than remaining a private experience; the nature of love; if the point of life is only to survive and reproduce; the concept of instant gratification; and many more. The perceived danger of these rides instigates Calvin’s asking of these questions; his physical vulnerability opens him up to profound conversations.

Fantasy

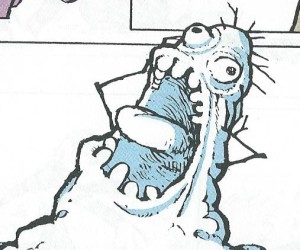

However, his sled rides are not truly dangerous. This where our fourth and final topic steps in: Fantasy. Calvin utilizes snow as a tool for pretend scenarios as well as a stimulant to imagine progress. In his mind, the toboggan runs are much longer, perilous, and death defying than they are in reality, as evidenced by the comic below:

Calvin also enters his dinosaur fantasy state when he imagines he is a dinosaur about to stomp on dozens of tiny snowmen. He and Hobbes panic to destroy the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons, a being he created that he must destroy. He fantasizes that the world has entered a new ice age and is overrun with Woolly Mammoths when there is only a half inch of snow outside. Spaceman Spiff makes a cameo as he is the only one strong enough to carry a giant snowball up into a tree to drop on Susie’s head. His snow forts are “impenetrable” and “indestructible,” even though they’re actually pretty tiny. Snow gives Calvin plenty of fantasy fodder, as do most other natural elements throughout the series.

The snow also importantly gives Calvin ideas for possible improvements to be made, which is engaging his imagination on another level. He imagines skiing with a jet pack on, using a snowblower to bombard Hobbes with snow, etc.

Calvin and Hobbes made extensive usage of winter scenery and snowy shenanigans throughout its run, primarily because it gave Calvin a powerful and limitless source for self expression. He used it to strengthen his relationships with his friends and parents, to indulge his narcissistic side, to experiment with different artistic approaches, to reflect on his questions about life, and to imagine the world as he would like it to be. It is Calvin at his most outwardly expressive and also allowed for some of Watterson’s best visual gags. The winter strips are integral to understand Calvin’s sense of self and his connections with those closest to him.