“Art is a fight to the finish between black charcoal and white paper.”—Gunter Grass

Most artists know that if they are drawing with charcoal, they might as well throw themselves down an old Victorian era chimney. While it’s a forgiving medium in the sense that even non-artists can achieve a level of mediocrity with charcoal, it’s typically not a medium for the meticulous, the anal retentive, the precise—a.k.a. comic artists.

This isn’t to say that all comic artists are psychotic, detail-obsessed mad hatters who stab people when a stray line appears on the lower corner of a panel. But if you look at most of the work from Marvel and DC or at nearly any genre of manga as well as that of numerous indie artists, you may notice that hard-edged lines play a significant role in the delineation of forms in a substantial amount of comics. So when an illustrator named Mark Siegel completes an entire graphic novel in charcoal, one cannot help but to wonder if he is on drugs.

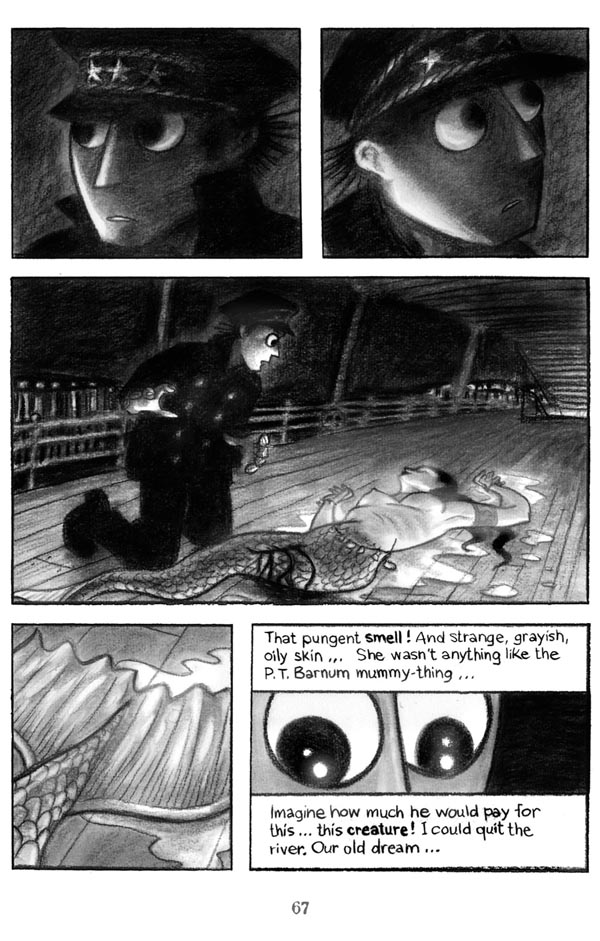

The graphic novel in question is Sailor Twain, or The Mermaid in the Hudson (2012), and it is rendered entirely in the messiest, albeit most traditional, drawing medium in existence. When people think of charcoal drawings, they think of graceful nudes cast in deep shadows or dramatic portraits of the inwardly tortured. They usually don’t think of googly-eyed cartoon sailors making out with mermaids.

Mark Siegel’s Sailor Twain is a powerful graphic novel about a sailor’s obsession with a mermaid in the Hudson River. The novel is a complex weave of archetypal themes, rooted in Mark Twain’s humor, Edgar Allen Poe’s darkness, Ernest Hemingway’s realism, and ancient Greek myth. Set around the Hudson River during the late nineteenth century, the story begins when Sailor Twain discovers an injured mermaid and, in tending to her wounds, develops a dangerous fixation on the creature. Forbidden love, quiet betrayal, heartless revenge, and blind infatuation create a cryptic yet adventurous mood that would fail miserably without the beauty of its medium.

That’s right. Sailor Twain could not have been successful in a medium other than charcoal. The gripping narrative, the charming characters, the enigmatic tone—all drift inside the hazy marks of charcoal like fleeting spirits. Unlike many other comics, Sailor Twain is driven by its medium as much as it is by the elements observers tend to elevate above the specific art tools. In fact,in an interview with Comic Book Resources(CBR) News, Siegel states:

Charcoal is a forgiving medium, it hints at more than it describes things. Not for the highly detail-minded. I tried inks and watercolors, but when I did a first test with vine and willow charcoal sticks, I suddenly saw the industrial revolution, the age of coal and steam, the perpetually rainy, foggy atmosphere I wanted for Sailor Twain’s Hudson River. It could be nothing else.

From panel to panel, industrial steam and stormclouds merge in the sky and on the black and white horizon. Rain cloaks the figures in bleak uncertainty. The underwater world of the mermaid is speckled with bright glowing forms from the river’s inhabitants and doomed architectural structures. The characters, defined with crisp, simple lines, stand out amid the soft, blurry backgrounds.

Okay, so what? Sailor Twain was created with charcoal on paper, and it suits the story. Who cares? We should care because Siegel has accomplished something that many comic artists never even attempt to do: he has sublimated his medium, from mere visual tool, to thematic device.

Medium isn’t explored enough in the analysis of comics. An artwork’s medium is ridden with hundreds (and, in some cases, thousands) of years of history in which artists, critics, and patrons assigned value to work based on more than just the cost of the materials or the quality and content of the work. A hierarchy has been established over the course of art history, and even though postmodernists love to pretend that we live in a world in which all media are created equal, painting is still at the top and drawing bows down before it, as the preliminary map, the sketch, the unfinished pre-painting, the flimsy skeleton. People, even trained artists, perceive drawing as the lines that need to be filled in with color, much like a children’s coloring book. The “tracer” scene from Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy (1997) explores this unfair degradation of the comic book inker.

The comic book world desperately needs works like Sailor Twain. We need comic books in which the medium is as prestigious as the story, characters, dialogue, and literary/visual devices. We need comic books that sublimate the medium to a level above “how it looks.” In Sailor Twain, the charcoal didn’t merely make the Hudson River. It is the Hudson. It is the mystery, the allure, the temptation. It isn’t merely an outline of shapes or forms. Charcoal is the literal and abstract shadow that obscures the characters’ desires and motivations. It is the fog the prevents the viewer from exposing the many secrets found in the narrative.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with the numerous comics that do not uphold their tools as actors in their stories. But works like Sailor Twain, Hyperbole and a Half, This One Summer, and Jimmy Corrigan definitely operate on another plane that isn’t frequently explored—a plane in which the medium isn’t solely a visual tool, but a contributor to character development, narrative depth, and thematic emphasis.