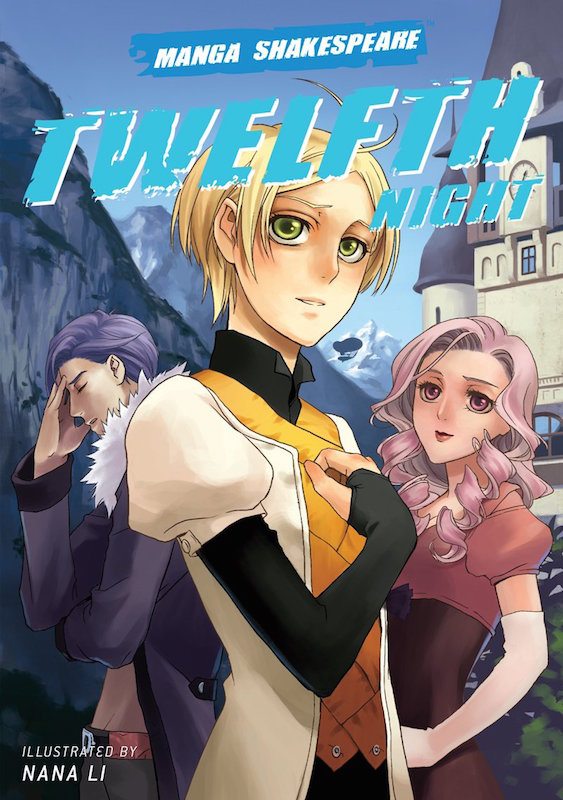

I was recently rereading Manga Shakespeare: Twelfth Night, and found myself surprised all over again by how much I like it, and how well it works. The Manga Shakespeare series, published by Amulet/Abrams in the US & Canada or SelfMadeHero in the UK, uses a “manga” drawing style (but the western left to right reading order) to present a pared-down script of Shakespeare’s plays, keeping his original words. It’s good.

I don’t usually appreciate comic book adaptations of “classics,” which are plentiful and often quite boring. Traditionally, a canonical literary text gets ruthlessly reduced and then shoehorned into a form that doesn’t really suit it, with too much writing crammed into speech bubbles and caption boxes, and stilted images without much action or movement in the panels. I’m thinking of the “graphic novelizations” of Great Expectations and Jane Eyre rumpled in a basket at the back of my eighth-grade English class when I was thirteen. These are supposed to appeal to reluctant readers. Sometimes there is a good close-up of a character’s face, but generally the Classics Illustrated series and their ilk feel to me like pictorial summaries of the classic texts they reduce, with all the juice squeezed out, rather than true adaptations into a new form.

There is, however, a major exception to this juicelessness: the many excellent graphic novelizations of plays. Playscripts intended for theatrical production that have become classics can be adapted into graphic novel form successfully, just as they can be performed on the stage successfully, because as written scripts they already exist in a form that is meant to be modified and embodied in a multitude of ways. Graphic novel adaptations of plays, therefore, kind of serve to produce the play for the page–taking it out of the realm of playscript and into the realm of realized visual performance and therefore adding to the many ways the script can be brought to visual life for a viewing audience. A graphic novel version of a play can be one version among many, rather than seeming as though it is trying to replace the experience of the “real thing” the way that a graphic novelization of a classic novel often feels.

Furthermore, the comic book adaptations of plays that are the most successful are the ones that realize this, and utilize the medium specific qualities of the creation of a graphic narrative to bring the script to life—just as a successful stage production would use the medium specific qualities of the theater to bring the script to life. Many comics, after all, do start as a script, in which the author lays out their plans for the dialogue and pictorial content of each panel. Sometimes this looks a lot like a playscript or a movie’s shooting script, and sometimes it is in thumbnails to indicate depiction. Regardless of form, a comics artist can then interpret this script in their own way, “staging” each panel based on what the author provides. This method implies a team of creators working together to create a comic book (author and artist, as well as inker, colorist, letterer) but in fact, single creators of comics also often create scripts before they draw out the panels of a page themselves.

Wouldn’t you prefer to read a graphic novel version of a play in which a comics artist treated the playscript like a comics script, turning it into a fully-fledged comic, rather than one where the artist treated the script like a “classic book” to be “adapted” for “reluctant readers?”

A 2011 post on The Guardian’s theater blog addressed this capacity for graphic narrative to house a playscript appropriately, in a discussion of a contemporary play being adapted as a graphic novel rather than published as a playscript at all. In the blog post, Kelly Nestruck notes, “reading plays for pleasure can be a frustratingly incomplete experience. Plays aren’t, after all, written to be read,” and further muses, “Imagine reading one of Harold Pinter’s plays and being able to see what’s going on during those enigmatic pauses–at least according to one cartoonist’s interpretation.” This casts the “cartoonist” in the role of the play’s director, which is a useful way to think about how plays might well be “produced” by adapting them for the comics page. Relatedly, Marion Perret, a scholar who writes about comics adaptations of Shakespeare, focuses on the vast range of interpretations to be seen in different adaptations of the same text. Just as the director interprets the text of the script in order to instruct their actors in what actions and emotions to convey, so, too, does the cartoonist convey their interpretation of the text of the script by depicting emotion and action.

Both the successful comics artist and the successful director will engage the conceits of their medium to successfully bring the script to life. Both comics and theatrical performance have medium-specific ways of requiring participation on the part of the viewing audience. That means they each draw in a viewer, in some ways differently and in some ways similarly. The participatory nature of comics is probably most famously addressed by Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics when he explains the way that readers are required to fill in the blanks between the panels to make meaning of the narrative. In the theater, audience members participate as well, by investing their attention and emotions in the actors in front of them. In comics, a reader generally invests singly, and in live theater, audience members invest together. This means that the methods of engagement will be different, but comics and theater are still two art forms that necessitate investment and engagement for the form to succeed.

For Manga Shakespeare: Twelfth Night specifically, there are a number of additional considerations that help the graphic novelization succeed as an adaptation. If you are trying to put together a production of Twelfth Night, the casting for it presents two of the challenges that are common in Shakespeare’s comedies: one, it has twins who are nearly identical to each other; and two, it has a woman character who masquerades as a man. In Twelfth Night, the casting is further complicated because the woman who masquerades as a man is, in fact, one of the twins.

For hijinks to ensue properly, the audience must find it plausible that these characters can be mistaken for each other, while also keeping track of who is actually where at any given time. In a theater setting, much of this can be achieved with actors’ costumes and body language; on screen, special effects including real and post-production can be employed. In a comic, however, I really believe those twins are nigh-identical because they are drawn that way. I really believe that everyone in the story confuses them, and believes that Viola is a young man named Cesario, because that is how the characters are drawn. My willing suspension of disbelief is pre-engaged.

The manga version of Twelfth Night circumnavigates the medium-specific play on gender and performativity innate to the Shakespearian stage, where all women characters were played by male actors, but it instead takes on the kind of play with gender representation familiar to a lot of manga readers. In other ways, too, it presents a shorter (but frankly, a lot of contemporary productions of Shakespeare make the plays shorter), thoughtful version of the play that engages with its medium.

Manga Shakespeare: Twelfth Night thus adds to the already-large number of good visual versions of the play, this time in a revisitable form.