Content warning: penises, breasts, rape of men.

EDIT, October 2016: this article is an analysis of Gfrorer’s work as a commentary on phallocentric patriarchy. Cis masculinity is consciously centred in the readings of these narratives.

I never really managed to think of a penis as a vulnerable thing until I caught the first fifteen minutes of Slaughter High. An 80s slasher that’s not remembered for any particular focus on the phallic, the acid-burned killer is introduced as a smooth-faced young nerd in a sequence of heinous bullying. Enticed into a shower with a confident jock babe, the kid finds himself mocked, gang-lifted, toilet dunked, all the while totally naked. His junk jiggles around, elastic and pale pink, and my heart broke a thousand times. Traditionally used semiotically as power, ownership and aggression, suddenly I saw the phallus in a totally opposite light. Associating a dick with an enforced breakdown of agency — against the grain of virility motifs and the idea of penile arousal as self-surrender or embrace of barbarism and the instinct to put others under siege — roundly improved my life. It gave me the roots of an ability to relate to (not to like, but to perceive a basic species-sameness with) even the pushiest man. He’s affecting his power, and underneath, he is weak. It broke the spell, really. Genitals have no Top Trumps magic, and genital-reliant gender has negotiable power. Men and me? We are equals. I understood this in a new way.

https://youtu.be/Qq_SKkuoYJ0?t=329

Julia Gfrorer’s work conjures this same spirit of reassessment, but in contrast I believe it does it on purpose. Slaughter High worked mostly in contempt, in jokes, in weakness as repulsivity; Gfrorer celebrates weakness as levelling. Her work grants vulnerability as a given for all people, and phallic genitalia, in ways that are usually reserved for women, and (weakness word!) “pussies.” Her regular endangerment of a penis and testicles, of men’s bodily confidence, and ultimately of a man’s conception of “his manhood,” is made wholesome, not vindictive, by its meta-thematic comparison to vaginas and womanhood. She makes them like us. She reveals that they are like us.

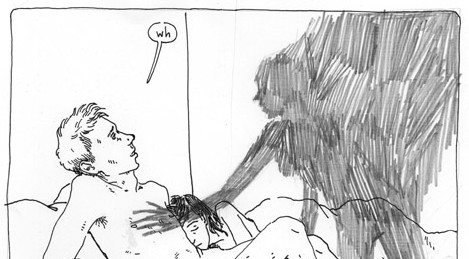

Sometimes in Gfrorer’s work, men are raped. This is something that happens in life with tragic frequency, but it is not something depicted in art or media too often, or too well. Of course the rape of women by men is very common, and in art and media too. We are not afraid to suggest women are victimised by men. When man’s rapes feature, the rapist is often a fellow male and the victim commonly queer; otherwise he may be a heterosexual who becomes subject to fears about their own sexuality subsequent to their rape by a man. In this way, fictitious rape of men is often kept reserved from a reader’s ideas about men’s heterosexual relations. Gfrorer prefers to consider rape of men directly within the realm of heterosexual intimacy; Gfrorer’s art contrarily positions women and vaginas as potentially rapacious, and the heterosexual, male penis as their prey. In Too Dark to See, a man in bed with his female partner is raped by a shadowy succubus; in Phosphorus a younger man is raped by some sort of pond spirit.

“I suppose the one-sidedness of it… there’s definitely always an examination of different types of power dynamics. Partly I think because I’m not writing about it for fun. I’m not writing about sex for it to be fun, like, “Hey guys, did you know sex is really fun? Surprise!” That’s not productive, to me. I want to find the thing that is challenging.” — Gfrorer during Katie Skelly’s Grotesquerie panel, readable at TCJ

The penises in Gfrorer’s work lie slightly curled, foreskins intact, or rest on supportive, shapeless balls largely without detail. They don’t glisten, or glow purple, or bulge angrily. They stretch like the penis in Slaughter High, and testicles can be gathered in a hand. These are mimetic penises, penises from neutral life — not localised, miniature stories about the straining horniness of the mighty boner. She neglects to give the penis its own stand-out narrative, makes it exist as metaphorically inert in the man’s narrative. In contrast to weaponised norms, the effect is of deflation.

With the lack of diegetic titillation, without the visual fetishism we are used to in works ascribed to the male gaze, no obvious joy is taken by Gfrorer’s narrative in the destruction of macho security, or the dismantling of the phallus as an image of power, domination and conquering. The aggressors are not wicked in the pantomimed sense, and provide no opportunity for cathartic, vengeful empathy with their predatory action. These are not comics to which one reacts simply, or perhaps even immediately. But the ability to recognise disempowered sameness and sexual victimisation in men is, for me at least, gratefully received. When one has a personal awareness of rape culture and emotional, behavioural relics from gendered and romanticised, sexualised predation, seeing those aspects of oneself reflected and validated is satisfying. Further, seeing one’s silent, ever-flexible bar-banging outrage register upon the image of the ghoul that allowed it to happen — the spectre of ingrained and traditionalised assumptions of masculinity, boyhood, maleness, countless graffiti DICK DRAWINGS, given shape as “a drawing of an okay, average man” — works some kind of healing magic.

When I say “average”, I mean normative; Gfrorer’s men appear to be white, able bodied, slim, they have no “foreign” markers in their stories. There is nothing in the stories to suggest that whiteness, for example, should not be understood as a demographic majority and a conceptual default. In the greater English-language and/or “western world” industries of visual entertainment intended for the man on the street, we understand that they are, that these men are facets of The Man. Gfrorer’s men are social winners in every way except for one: the specific victimisations they are suffering in the moment.

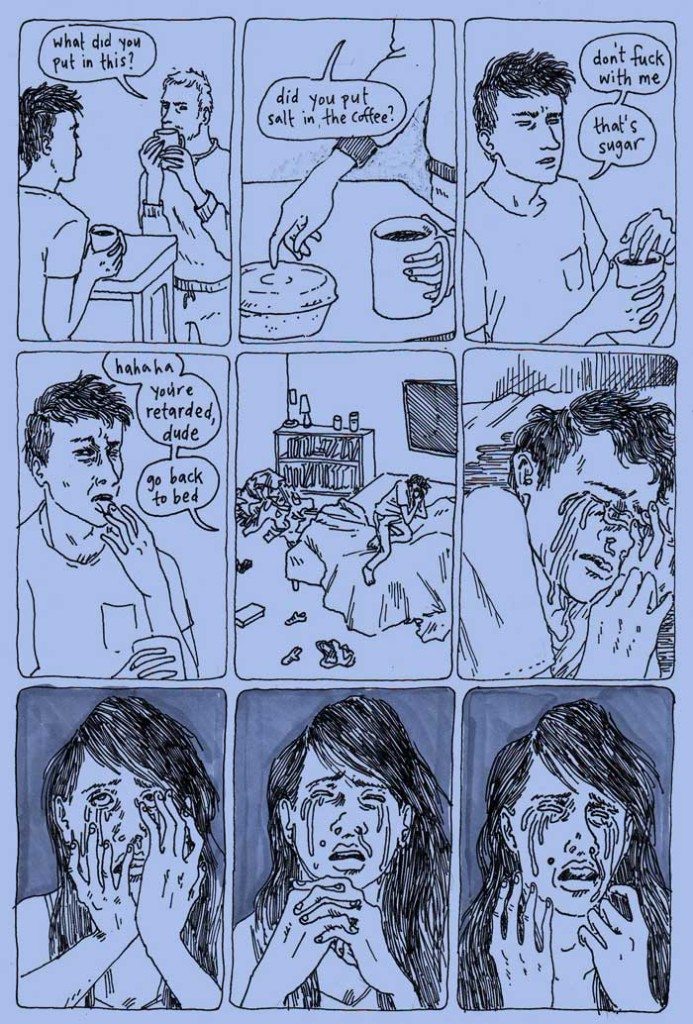

Seeing men suffer intimate victimisation and casual cruelty from people who don’t share their gender (and conversely, seeing women casually, confidently abuse men, with no repercussion) — seeing the registry of cruelty and intimate victimisation upon smooth men’s faces, bodies, and seeing this behaviour as cooly delineated as Gfrorer does it — feels like the release of a held breath. Gfrorer tells these stories without malice, with no denial of tragedy, with no captioning, no narrative script; her work, without fail, is an external and voyeuristic but fully experiential diegesis that subtly, through focus, encourages sympathy or peership with the men she draws being betrayed and violated. This feels like a challenge to my compassion and connection. Not to welcome #allmen as people who understand what it is to live within womanhood, but to truly see the unfairness and lies that support phallocentrism and patriarchy. Her work leaves me with a lot of thoughts: men aren’t “stronger,” no matter how many you meet who could knock you down. A penis is just a piece of flesh that dangles. Men have no more idea about how to relate to themselves than anybody. A man is in danger, as well, and cannot process it better than you. There is no shield around a man innately; the shields he has are all constructed. If your lover has a cock, don’t be afraid, because you’re holding something that can die.

Men are just as weak as women, but manhood offers certain denials, or lucky breaks, for some reason. To escape the rock-solid conception of gender binary that many of us grow up with, this is necessary work to learn.

2016’s Dark Age and 2012’s Black is the Colour establish a baseline impatience with masculine posturing. Dark Age’s naked, male protagonist finds himself trapped in a pitch-dark cave for an unmeasurable length of time (unless time is measured in panels, in which case: sixty six), waiting for his female lover to return with help and light. A state of complete physical passivity. Black is the Colour kills sailors while mermaids chat nonchalantly about the men’s probably sexual inabilities, callowness, and lack of value. A sailor cast adrift by his own crew discusses the homosexual sweetness of his early intimate encounters and tries to retain faithfulness to his shorebound wife, resisting the come-ons of a pleasant, engaging naked mermaid, whilst dying of exposure, hunger and probably tuberculosis. In the end, he dies and is consumed. Once again, Gfrorer offers a struggle with surrender, ultimately lost, for a man of normative privilege.

2014’s River of Tears covers a short time for a man whose ex-fiance is struggling with addiction and suicidal ideation. Her need to impress upon him the depth of her suffering spoils his night out, spoils his sleep, spoils everything…she dominates his psyche. Eventually he dreams of her crying, being embraced by Death, and the comic ends. He drowns in her problems, given over to his irrelevance in the face of her needs. The simple subversion of a man’s pain not only proving accessory to a woman’s story, but of a man’s story (he began as the protagonist and vanishes, a twenty-first century Marion Crane) being entirely hijacked by a woman’s narrative leaves me speechless. Why is this structural upheaval so rare? Hanging men out to dry, again and again. Weakening the dominant narrative, swimming against the tide. Gfrorer can make her art, but if you become her audience and take it in, she can also make a change for you.

In an interview with Sean T. Collins, at the start of their professional association, Julia Gfrorer says:

My audience’s comfort level is really none of my concern, because I have no context to predict whether comfort or discomfort will occur in my audience as a result of my work

For my part, context suggests both.