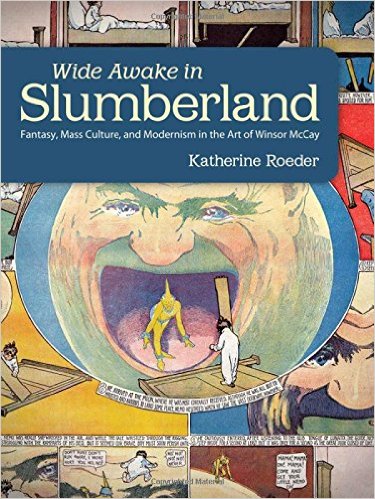

Wide Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay

Wide Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay

Katherine Roeder

University Press of Mississippi

January 1, 2013

Given the current situation of newspaper comics, it’s sometimes hard to believe that a century ago they were big business, wildly popular, and the source of some of the most innovative comics art in the medium’s history. Recapturing that lost world can be a challenge, but Katherine Roeder’s Wide Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay, a book on the art and career of the creator of one of the best newspaper strips of all time, does an excellent job of conjuring that lost world back up again. It’s a beautiful book, positively packed (particularly for an academic text) with full-color reproductions of McKay’s comics. Even better, it’s good, and it does a thorough and engaging job of explaining the world of McKay’s comics to readers. The medium, the industry, and the context of comics have changed drastically since Little Nemo in Slumberland debuted in 1905, but Wide Awake in Slumberland provides an excellent guide to understanding the state of all three in McCay’s prime.

Scholars have usually seen comics, and the mass culture of which they were a part, as somewhat more conservative (because popular) art forms, which were instinctively opposed to, or at best ambivalent about, the dazzling formal innovations that marked the high art of modernism. Roeder, by contrast, argues that this is a false dichotomy, and for her evidence, she looks to McCay’s comics themselves, which cleverly incorporated modernism into their visuals.

Roeder’s overarching argument has to do with the relationship between comics and modernism in art at the dawn of the twentieth century, when both comics and modernism were just getting started. Scholars have usually seen comics, and the mass culture of which they were a part, as somewhat more conservative (because popular) art forms, which were instinctively opposed to, or at best ambivalent about, the dazzling formal innovations that marked the high art of modernism. Roeder, by contrast, argues that this is a false dichotomy, and for her evidence, she looks to McCay’s comics themselves, which cleverly incorporated modernism into their visuals.

“McCay was instrumental in creating an audience for comics by both acclimating them to the visual language of comics and dismantling these selfsame conventions before their eyes,” she writes. “This type of interrogation of medium and self-consciousness about aesthetic practice would come to define modernism in the twentieth century” (9). Rather than being an anti-modern reactionary, in Roeder’s telling McCay is a gifted cartoonist who used modernism to make some nuanced criticisms of the modern life of his time.

It’s a great boon to Roeder’s arguments and to the book in general that Wide Awake in Slumberland is beautifully and copiously illustrated with full-color reproductions of McCay’s comics.

Thanks to these generous helpings of reproductions, it’s possible to see for oneself what Roeder is talking about when she discusses McCay’s visually innovative work.

It’s also possible to get a sense of the breadth of McCay’s talents as an artist, not only through his work on the earlier strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, but also through his appearances on the vaudeville circuit and his role as a pioneer in the development of animation. Thanks to her decision to discuss McCay’s creative output overall, Roeder’s discussions of the interplay between the landscapes of Slumberland and the cityscapes of turn-of-the-century makes both more accessible. Partly Roeder accomplishes this by explicating the themes in McCay’s work that the passage of time has rendered obscure: the concept of Rarebit Fiend, for example, relies on the forgotten Victorian cultural commonplace that eating too much cheese for dinner could lead to weird dreams. Without knowing that adage (or that Welsh rarebit is a cheese-based dish), a good chunk of the humor in McCay’s earlier work, which Roeder convincingly demonstrates was innovative and interesting in its own right rather than just as a prelude to Nemo’s adventures, would go right over readers’ heads.

Roeder’s chapters entail a thorough discussion of the interplay between McCay’s work and other elements of mass culture at the turn of the twentieth century: the relationship between the amusement park at Coney Island, the traveling circus, and the landscapes of Slumberland; the clever ways in which McCay borrowed the visual grammar of department store windows both to interrogate the era’s new conception of children as consumers and to attempt to promote tie-in Nemo merchandise; the carefully calculated mixed-class appeal of Little Nemo in particular, which transcended class-based ideas about childhood, child-rearing, and fantasy in order to pitch the strip as widely as possible. All of these discussions, coupled with the fact that Roeder is of the “restate everything one more time at the conclusion of the chapter” school of academic writing—this strategy can be a little dulling when sitting down to read the book cover to cover, but is a huge help to graduate students cramming for seminars—mean that the final chapter, in which she makes some of her most important points in terms of overall comics scholarship, is well supported.

Specifically, it’s very easy to read the ambivalence about new forms of mass culture in the early twentieth century, and the social changes they entailed, as a form of conservatism on the part of comics creators. In discussing McCay’s adult-oriented strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, Roeder highlights the fact that, even as the strip portrays modern urban living as literally nightmarish, its formal operations “complicate its indictment of urban life. From the architecture of the page to its placement within the newspaper, the comic strip mirrored the freneticism of city life. The disconnection between its form and content underscored the paradox of the displaced urban subject” (10)—which is to say, just like the protagonists of Rarebit Fiend, McCay and other comics creators were caught in the double bind of modern life and mass media: overworked, underpaid, and never totally certain that their lives might not have been easier in older, simpler times. Far from being a discordant note in the operation of early comics, the power of this tension was no small part of their success, and Roeder’s work helps us to understand McCay and his work as more than just the sum of Nemo of Slumberland, even as her conclusion lays out a long and illustrious list of comics creators whose work is openly indebted to Nemo in particular.

Indeed, my one serious regret about Wide Awake in Slumberland is that I could have read a much longer study of these influence-ees; among them are many classic comics and some of my own personal favorite creators, such as William Joyce and Bill Watterson. It would certainly make a really great museum exhibition (which is where I first encountered Little Nemo in its full-size, full-color glory; the beautiful full-scale reproductions of the strip that have been published in the last decade or so are well worth seeking out). “Wide awake” was a way, at the beginning of the 1900s, of describing consumers who were alert to the operations of the marketplace; by the end of her study, Katherine Roeder leaves her readers alert to the operations of Winsor McCay’s art both in his own output and in his work’s afterlife.