CW for mentions of child abuse

What is it that sets Fantastic Four apart from other team books? Though the roster rotates slightly throughout the years as characters move in and out of each other’s lives, everybody knows the Fantastic Four will always be Susan Storm, Reed Richards, Johnny Storm & Ben Grimm. This consistency has allowed for the development of a very strong family unit, one which has now become the basis of most F4 stories. But when we say family is the prevailing theme of the comic series, what exactly does that mean? This is the first entry in what will hopefully be a series of essays exploring the ways in which ‘family’ is understood throughout Fantastic Four.

It’s not uncommon for characters in action and superhero comics and stories to be, in varying definitions of the word, orphans. There’s many reasons for this, one being that it evokes immediate sympathy from the reader. It can allow a character to have a ‘clean slate’ with little to no exposition needed to describe their background or situation. But most interestingly, it frequently allows the character to live an unorthodox lifestyle outside of conventional norms.

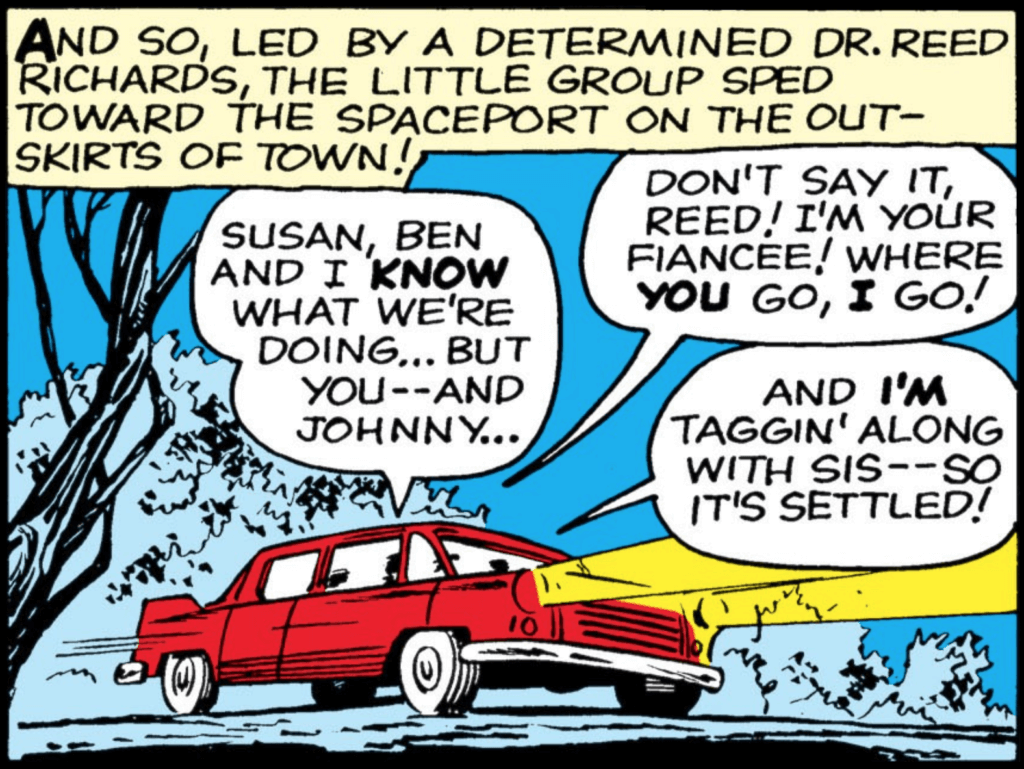

At the point in the story where Fantastic Four (1961) begins, all of our main characters are, in some form, orphans. This factors into their superhero origins: Reed, effectively left to his own devices in his teen years by his extraordinarily wealthy (and mysteriously absent) father, is able to use this fortune to build his infamous rocket to the stars. Ben’s family had passed in his childhood, leaving him in the care of an aunt and uncle he struggled to connect with. Susan and Johnny similarly no longer have parents around to forbid or even discourage them from joining Sue’s fiancé on a flight test in an experimental rocketship.

But it also factors into their everyday life: No secret identities are maintained by the team (aside from a teenaged Johnny who does a very poor job of guarding his, but whatever, we still love him) as there are no immediate family members who need to be protected from the F4’s roster of supervillains. This affords them all a certain amount of freedom, but at the same time isolates them from the civilian world.

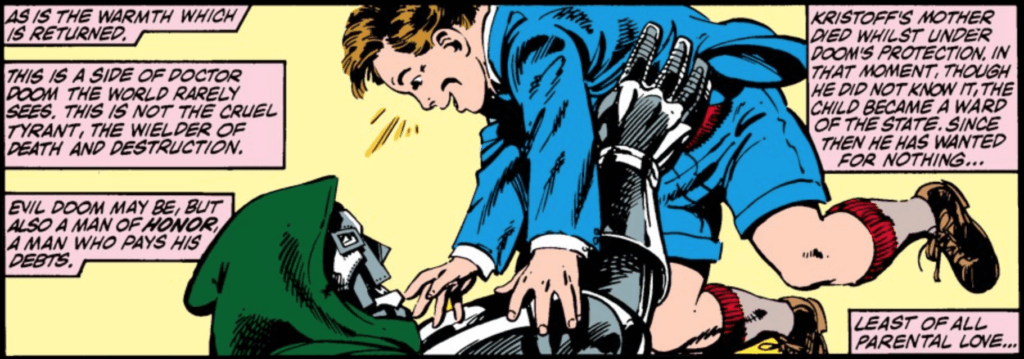

Adoption can be seen as the narrative consequence of the orphan’s story, especially in comics. Across all genres, the comics format generally demands a supporting cast: other characters for the protagonist to care about, be motivated by, and to exist alongside in order to drive the story or create conflict. There are quite a few adoption stories throughout the history of Fantastic Four, with one of the very first being that of Kristoff Vernard by none other than the F4’s collective archnemesis, Victor von Doom. Victor’s attitude towards the young man (who came into his guardianship after Kristoff’s mother was murdered in front of Victor) at first seems stern, but with an underlying kindness and genuine love.

We quickly see that love twisted, as the sole subject of Victor’s love becomes the sole bearer of his anger and abuse. Kristoff isn’t even the only supervillain adoption story we get in Fantastic Four: Alicia Masters, Ben’s on-again off-again girlfriend and later wife, is the adoptive step-daughter of the equally abusive Puppet Master. While both Kristoff and Alicia go on to join the loving-yet-dysfunctional Fantastic Family, the image of adoption that Fantastic Four portrays remains marred. In both cases, the adopter was an ‘evil’ individual who ends up using the person in their care for literal supervillain schemes. This image existed in contrast to Franklin and later Valeria, who are biologically conceived (in wedlock, even!) by their superhero parents, Sue and Reed.

The status quo of the F4 is eventually shifted in Jonathan Hickman’s Fantastic Four run that introduces the beginnings of an auxiliary group called the Future Foundation, which was essentially a small boarding school. Like the Fantastic Four themselves, several of these children were parentless and ended up becoming the legal wards of Reed and Sue (specifically Vil, Wu and Bentley Wittman Jr.). Sue is later shown as fiercely defensive of the young team, and it becomes clear that she considers them all as dear to her as her own children. But the feeling that Ben, Reed and Johnny are only tangentially involved in this new extended version of the Fantastic Family is ever present throughout this run, and leans into one of the persistent problems of Sue’s characterization: that she is overwhelmingly, to the detriment of any other character development, a mother figure.

This new family structure was one that served to socialize and teach the younger generation while allowing our adult cast to take on the roles of parents, guardians and teachers, not unlike what we have seen for years in X-Men titles. The Future Foundation presented considerable opportunity for writers to explore the theme of family beyond the traditional biological relations we had seen up until this point, but this new structure didn’t last: after the Secret Wars interlude, the Future Foundation took off on their own adventures in a title that lasted only five issues before cancellation.

The team returns in Fantastic Four #26 (2018) for a remarkably unceremonious sendoff, in which each member of the team is quite literally sent back to where they came from, regardless of the relationships they had developed during their time together as an adventuring team. This includes the four Moloids (Tong, Korr, Mik and Turg) who are apparently sent back to Subterranea – a place they had been ostracized and outcast from.

The disbandment of the Future Foundation feels like an admission of defeat: they apparently don’t fit into the current storyline, and they’re not worth the effort of trying. The familial relationships (including the team’s only two LGBTQ members) they had spent years building are simply gone for the foreseeable future. The absence of the Future Foundation, but not Franklin and Valeria, from the main title adds to Fantastic Four’s history of flawed adoption storylines and establishes the narrative that adopted children are not fully part of the family, liable to be discarded when no longer needed or wanted.

Other new developments to the Fantastic Family structure take place after Ben and Alicia’s marriage in Fantastic Four #5, back in 2018. Both Alica and Ben have taken on parent and guardian roles throughout their histories, being closely involved with Franklin and Valeria’s upbringings throughout their lives as the siblings’ aunt and uncle. Ben has also been something of a mentor to a variety of young heroes, from Vance Astrovik/Justice in The Thing (1983) to Lunella Lafayette/Moon Girl in Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur (2015).

We even get hints throughout the years (especially in this year’s X-Men/Fantastic Four) that Franklin relates more closely to Ben than Reed, and is more open and honest with him than his parents. So it’s little surprise to the reader that the newly married couple want to have children of their own. In Fantastic Four #12 (2018) we find out, albeit euphemistically, that Alicia and Ben are not able to conceive unless Ben is in his human form, which he is reverted to for one week each year. Largely due to supervillain schemes, to make a long story short, Alicia wasn’t able to conceive during this allotted time period. There was no magic or science that could fix this problem for them. Intentional or not, this predicament seemed like a pretty clear allegory for infertility.

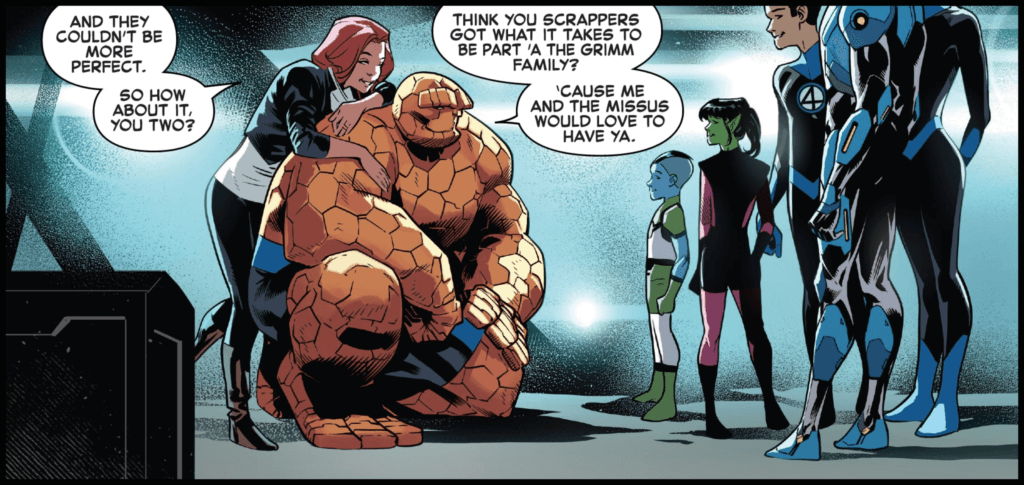

This plot was briefly shelved until just two arcs later when Ben and Alicia adopt a pair of alien children at the conclusion of the Empyre event in Empyre: Fallout Fantastic Four. The two children, N’kalla and Jo-venn, are rescued by the F4 from a life of perpetually battling each other in a gladiator-style arena, re-enacting historical battles between the two adversarial alien races they hail from: the Skrulls and the Kree. This serves as a rare but poignant thematic callback: both Ben and Alicia themselves were raised by non-biological parents. But is the message we take from this development that their failure to conceive naturally is what left room in Ben and Alicia’s life for N’kalla and Jo-venn? What does this say about adopted children if adoption is just the “backup plan” for those unable to conceive?

Though current writer Dan Slott has promised that these new family members are here to stay, Fantastic Four’s overarching theme of “family” could easily be deprioritized again by that perpetual cycle that seems to afflict all long-running comic titles: the impulse to repeatedly return the characters in a story to their original state, a yearning for the good old uncomplicated days of comics that, with some critical examination, never seemed to actually exist.

Adoption, childhood and generational trauma, parenting and socialization are all topics Fantastic Four has examined in the past, with varying degrees of introspection. The book now faces a unique opportunity that few other superhero titles share: the chance to be a truly modern, dynamic and interesting exploration of what ‘family’ really is. One can’t help but wonder, though, if that opportunity will be seized, or squandered alongside so many of the other rich story opportunities Fantastic Four has passed over throughout the book’s history.