Editor’s Note: This author has chosen to remain anonymous, due to the very specific geographical knowledge contained here.

I grew up in Stanwood, Washington, a small town a couple miles off the interstate. Its got that quintessential small-town feel: the dairy farms handed down through generations, the locally owned businesses being edged out by big chains. The racism, the churches on every corner.

Stanwood has just a few claims to fame: Colton Harris Moore, the “Barefoot Bandit” known for stealing and flying planes as a self-taught teenager, that guy who tried to sell bulletproof vests and night-vision goggles to terrorists in Somalia, and, amazingly, one of the first female cartoonists to receive syndication.

Oh, and the time that a local church was so embroiled in the public school system that we made national news.

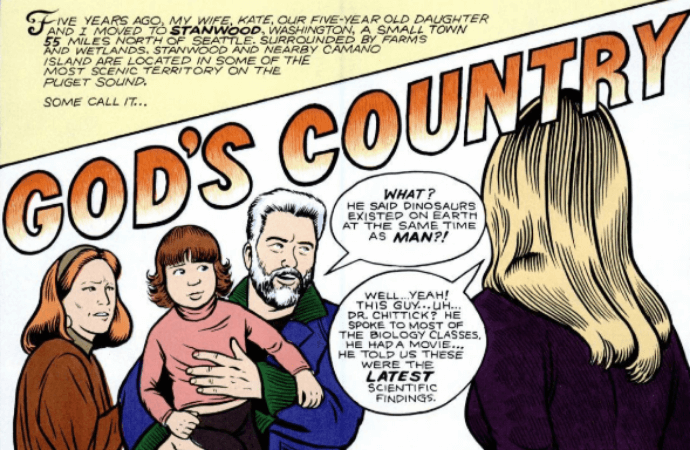

I remembered this little detail recently and asked my grandparents, lore-keepers for the entirety of Stanwood, about it. My grandpa pulled out a perfectly pristine copy of Mother Jones magazine from April 1994 and handed it over. Lo and behold, the story was told in comic format by Mark Zingarelli, an award-winning cartoonist who lived in Stanwood for a time.

I wasn’t familiar with Zingarelli’s work before reading this comic, but his work—a classic style that now looks a bit retro—is perfectly suited to both the subject matter and Stanwood’s glossy, good ol’ hometown feel. Zingarelli told the Everett Herald, Stanwood’s nearest “big-city” newspaper, that he chose to tell the story in comic form not just because it was the form he typically worked in, but also because it was more accessible, an eye-catching version of a story that people around the country needed to read.

It’s bizarre to see sights so familiar to me, such as the video store that closed down decades ago, rendered in such a cartoony style. But the story, too, is familiar. Though the magazine came out in 1994, when I was just six years old, the story wasn’t finished by the time I attended middle and high school.

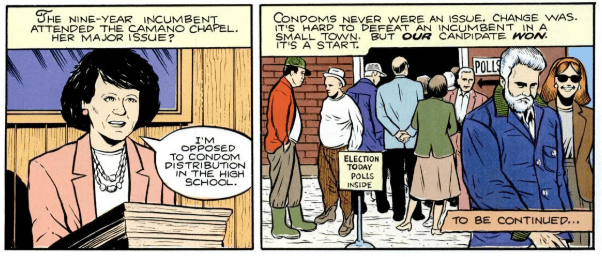

Throughout “God’s Country,” Zingarelli relays his experience with the Stanwood school board. After the babysitter for his child informs Zingarelli and his wife that she was taught that people lived with dinosaurs, alongside news that Stanwood had implemented an abstinence-only sex education program, they discover that much of the school board and the local government consists of members of the Camano Chapel, a fundamentalist Christian church on Camano Island.

By reaching out to national organizations like the ACLU and the National Center for Science Education, as well as dedicated grassroots organizing, Zingarelli and concerned members of the community, including some teachers, managed to make change. They elected Mary Beth Fisher over a nine-year incumbent member of the Camano Chapel to the school board. It wasn’t much, but it was a start, and Zingarelli notably ends the comic with “To be continued …”

Stanwood’s reaction to the comic was predictably divided. Some, like my family, who had previously spoken up about Camano Chapel’s involvement in the school system and been subsequently snubbed for it, were glad to see the issue receiving widespread attention. Others felt it was an attempt to smear the entire concept of religion. One of my favorite high school English teachers even contributed a comment to the Herald’s piece on “God’s Country,” suggesting that the Camano Chapel not the only church with its hands in the Stanwood school system, but things actually seemed to be on the mend.

As a student in Stanwood’s school system from around 1992 to 2007, I can, unfortunately, say that that was not the case. Zingarelli was right to end with the note, “To be continued …,” because even by the time I was in high school, there were still notable intrusions into our education.

As the Old Camano website points out, by 2002 most of the school board named in Zingarelli’s piece had left or been voted out of their positions. But that’s at least ten years with the religious right influencing school curricula and a wealth of other members to vote into prominent positions, and it wasn’t easy to get rid of.

Our sex education is where the influence was clearest. We had the standard binary “boys in one room, girls in the other” approach in elementary school, where we primarily learned about periods and tampons. In middle school, things were … different. A woman came to speak to our class and taught us there were three kinds of kissing: peach, plum, and alfalfa. Say the words aloud. Notice the way your mouth moves. Imagine a room full of preteens from a farm town being unable to hear the word “alfalfa” again without breaking into a fit of giggles for the next ten years.

The same woman also taught us that if a girl “alfalfa” kisses a boy, it’s her fault if she gets pregnant. She didn’t discuss how such a thing might happen, nor how a girl has a right to kiss someone without the implication that she’ll have sex with them. It was suggested that boys were wild, sex-crazed fiends, who, when presented with a mouthful of “alfalfa,” would be unable to stop themselves from doing whatever it was that came between kissing and a baby—we certainly weren’t told what that was.

We were told, however, that condoms were “a tool of the devil.” We weren’t told what condoms were, only that they were somehow connected to Satan. I didn’t see a condom until my friend brought a pack to school to blow up like balloons, and even then I only knew abstractly what a condom was for. You used it during sex, apparently, but what for? Nobody had told me.

At the end of this lecture, we were told to sign a little card that acknowledged we understood what we’d been taught. It also included a pledge that we would remain abstinent until marriage. I don’t remember what exactly I wrote, but I do remember feeling angry and confused by the entire thing—I hadn’t learned anything, and I didn’t like that I was supposed to agree to not do something I didn’t fully understand.

In high school, there was an attempt at giving students actual information, but what sex education you got depended on what teacher you had. In my case, I had the teacher who mysteriously fell ill right around the week he was supposed to teach sex ed; usually, that meant substitutes that would stammer their way through the curriculum or put on a movie or something. Though it didn’t feel like it at the time, I lucked out—my substitute teacher unabashedly told us about testicles and ovaries and caused an entire room full of freshmen to look at one another as if our bodies were somehow more strange and alien than they’d been just hours before.

But we also had another teacher, a youth pastor from one of the local churches. He showed up to class with a casual, relaxed attitude, as youth pastors do, and told us about a young woman who wandered out into the mudflats and was sucked into the channels. She sunk to her waist, unable to free herself. They brought a crane out there to pull her out, and the suction was so great that the crane tore her in half and she died.

“That’s what premarital sex is like,” he said, with all the gravitas a man in the typical youth pastor uniform of khakis and an inoffensive sweater can muster.

I don’t remember the rest of the lecture, because by this time I was old enough to be heavily invested in romance novels and armed with the knowledge of all those body-themed books well-meaning relatives give you in secret. Some of them even mentioned masturbation, a word I had literally never heard spoken aloud. There was only “alfalfa” kissing and premarital sex, which would probably lead to death or dismemberment.

This isn’t an exaggeration—that scene in Mean Girls where the PE teacher struggles his way through sex ed, suggesting that if you have sex you’ll get pregnant and die, is literally my high school experience, only minus any attempt at being helpful and certainly no mention of condoms. As you can imagine, the teen pregnancy rates at my high school were astronomical. We didn’t have a Planned Parenthood in town, and I think few people would have known where to turn for information online at that point. Despite the abstinence pledges, teenagers did have sex and did get pregnant.

Zingarelli’s comic was primarily focused on how Stanwood taught Creationism as a viable scientific theory, and we hadn’t yet escaped that by the time I was in high school, either. One teacher laughed her way through her lecture on the Big Bang Theory, scoffing at concepts like “millions of years” and that “something” could come from “nothing.” In other classes, teachers tossed out words like “intelligent design”—even if they weren’t allowed to teach it, we were still aware of it.

When I tried to start a Gay-Straight Alliance in high school to combat our school’s rampant bullying problem, I was told no, because then the school would have to allow an anti-gay club. But First Priority, our bible study club, was allowed to proselytize at lunch, handing out sodas with Bible passages attached and sitting down at lunch tables to ask, in grave tones, whether anybody had ever died for you.

Things are different now, at least according to people I know who graduated after I did. They got real sex ed, and the teachers who laughed their way through science lectures retired or moved. That is, undoubtedly, a good thing.

But Zingarelli’s comic was created back in 1992. Over a decade later, I was still experiencing it, the “To be continued …” lasting far longer than it had any right to. Its art style looks retro, but its themes, its events, are not. They’re still happening—if not in Stanwood, then elsewhere.

The comic, and the Mother Jones issue it appeared in, are eerie. Not just because it’s strange to see the Video Farm—a name that is so incredibly Stanwood that I never questioned how weird it was until this exact moment—appear in Zingarelli’s art style, but because they’re eternally relevant. In 2019, these questions are surfacing again. How entrenched is the religious right in our education? What can be done to stop them? What effects are these ideologies having on children? Is grassroots organization enough when it took over a decade to (hopefully) oust the Camano Chapel—which one teacher said was not the only church to blame—from the public school system?

I’m grateful that my grandfather hung onto this issue for almost 20 years. I’m glad the comic ended with “To be continued …” Because it has continued, and it is continuing, and it will continue, until we forcibly stop it.