Content Warning: this retrospective mentions abuse and sexual assault

If I were to do a quick Google search, I could find webcomics featuring anything I can imagine: gay centaur Westerns, wild overarching epics with diverse casts, and autobiographical tales featuring authors of almost every gender, sexuality, and race. While comic books on the direct market keep slowing in sales, the realm of webcomics has brought on fantastic new niches. I could probably list any Universal Monster and find at least one queer webcomic made by someone who greatly thirsts for Boris Karloff.

This was a long time coming. In the 1980s and 1990s, American independent comics had been previously isolated to small press, but were beginning to pick up nationally thanks to newly formed comic shops. These were never huge, outside of relative flukes like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and The Crow, but many enjoyed cult followings. Stories like Elfquest, Cerebus the Aardvark, and A Distant Soil all enjoy a sizable audience to this day. At the time, the majority, though not the entirety, of LGBT+ webcomics were made by people who either were not part of the queer community or not openly so. Women, like Donna Barr and Colleen Doran, wrote about gay men in their fiction, and the guys usually wrote fetishized content surrounding lesbian women.

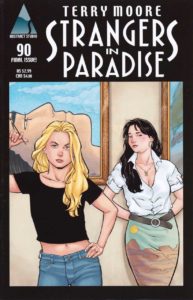

Strangers in Paradise by Terry Moore, however, was said to be a huge outlier of the icky male-gaze surrounding LGBT+ themed comics at the time. Half romance comic, half crime drama, the series follows former sex worker Katchoo, who works as a budding artist while navigating a love triangle with her friend Francine and a Catholic ex-Yakuza named David. Before it hit its second volume, SiP had already been nominated for several awards, including more than one Eisner nomination. Much of its success stemmed from its inversion of traditional romance tropes and its focus on two bisexual women and a straight Asian man. While not terribly famous today compared to contemporaries in the same field, SiP has a devoted fanbase due to its discussion of feminism, body issues, and queer content. It touted itself as being “the comic to give someone who doesn’t read comics” due to its sizable female audience and lack of clear fantastical or superheroic elements typical of most comics at the time.

It is also a zany, dated piece of guilty pleasure fluff stretched across 19 volumes that I adore to pieces, despite its very, very clear issues. Just to start with, here are some of the outrageous plot elements in this series: a ghost grandma, a lesbian Jack The Ripper, two “Crash-The-Wedding” plots, a crossover with early ’90s Image Comics, an entire dream sequence introspecting the queer elements in Xena: The Warrior Princess, mafia-hired sex workers infiltrating the White House, and multiple timelines with multiple endings. I remind you, this is a crime drama/romance work meant for everyday readers. It is hilarious how ridiculous this series gets considering its core audience. It’s like Terry Moore started each volume by throwing darts at a board filled with fever-dream scribbles and plastered whatever he landed on into that week’s script.

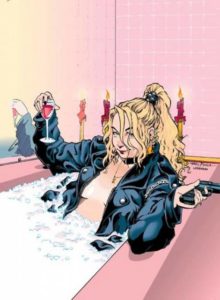

Where Strangers in Paradise really falters is actually embedded in the elements that garnered it praise in its heyday. To understand, let’s wind back a bit. The overarching narrative is that Katchoo, a Chicago sex worker with a troubled past, becomes ensnared in high level mafia activity and tries to escape, only to be forced back by circumstances partially out of her control. By the end, she is the head of the crime family that damaged her so badly, feeling compelled by her situation to continue, and ultimately and subconsciously by her own need to embrace an environment that reflects her own self-image. In the tradition of The Godfather and Scarface, Katchoo’s story is of a person who tries to change what dirty part of the world they can, because they can’t change themselves. This, in all honesty, is a great crime character. However, a character unable to change or adapt does not make good dating material, and thus, does not make a great core for a love triangle. Katchoo often—frequently, in fact—lashes out at both of her love interests, taking words and twisting them into weaponized arguments that cast her in the right every time.

As an example, within the context of her private life, Katchoo is a professional painter with a preference for drawing real-life nudes. When David, her then-boyfriend, refuses to pose nude, Katchoo throws a gigantic fit. From his perspective, he thought he was just going to pose in some jeans and a t-shirt, and he’s uncomfortable being drawn nude for an art piece that might be sold off or possibly be shown at public art galleries. This is a completely normal, human response. Katchoo responds by violently breaking up with him, accusing him of never sharing any part of his life with her, and throwing him out of her house. While some of her secondary points remain valid, she is completely in the wrong here, and the worst part is that Moore is unable to see her faults, or most likely is unwilling to develop her past this point until around issue# 64, which is well over the halfway point.

When Katchoo finally comes to her senses, what makes her realize she was in the wrong was not that she was being a complete ass, but that she realized that David kept his life from her because he was abused during most of his childhood. From a story perspective, this ejects any character transformation out the window because Katchoo’s found a scapegoat for herself. She wasn’t in the wrong; it was just that she didn’t know some fact that would have made everything better if she did know. This is a classic case of abuse mentality, and the fact that the author rarely addresses this is incredibly distressing.

There are numerous occasions where this happens. At one point, Francine is making Katchoo breakfast and talks about how their current life is better now that their brushes with the mafia and hired killers are seemingly over. Francine says that their past few years together had been like a “nightmare” to her. In response, Katchoo starts breaking furniture and uses that one word “nightmare” to start an intense argument. She destroys things, she yells at Francine, and when Francine locks herself in a room, Katchoo breaks the door down. There is no excuse for this, because I personally know abuse victims who’ve had this exact scenario happen to them.

Nobody really calls Katchoo out for her horrifying behavior, and on average they never act like Katchoo is a toxic person to be around. Her behavior eventually mellows out, but it’s done so hastily that it’s almost without warning. It doesn’t have a clear connection to her feeling any remorse for what she’s done to Francine and David in the past and almost everything to do with how she feels their overall relationships are flawed; so every scene where she shows her true colors before that point still leave a bad taste in my mouth.

At best, she has intense rage issues, possibly stemming from PTSD or other applicable disorders due to her abusive upbringing. At worst, she’s a character that actively creates drama for the writer and never grows as a person, and the rest of the cast just accepts it. It’s ridiculous how much of the core drama can be directly tied to her inability to function as a reasonable adult. This would be fine for a singular graphic novel, but again, 19 volumes of this nonsense makes a mind weary.

I am in fact so weary, that for now I’m completely out of wind. In truth, this is only a fraction of what’s plaguing this series, and if I posted the full version of this article, the editors would fire me for overloading the audience with my inane rambling. Next time, we’ll be looking at some of the other elements that Strangers in Paradise dropped the ball on. Let’s just hope I stop talking about toxic relationships for a while.

Spoilers: I don’t.

“This is the comic to give someone who doesn’t read comics. This is the book that will prove that comics are not only for kids anymore, but that as an art form, they can aspire to a cohesiveness that prose and painting alone, individually, lack.”

–PlaNETLar (On the back of volume 2, 1996)

4