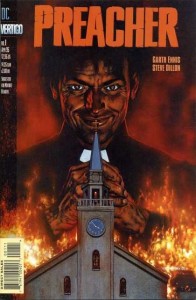

This past March and April, I read Preacher for the first time, which feels like comics sacrilege in 2016. Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s seminal late 90s creation about a man from East Texas who is burdened with glorious purpose—or, more accurately, the spawn of an angel and a demon—is held up alongside The Watchmen (which I have unsuccessfully tried to finish twice) and The Sandman (haven’t read that one either) as comics reading requirement.

This past March and April, I read Preacher for the first time, which feels like comics sacrilege in 2016. Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s seminal late 90s creation about a man from East Texas who is burdened with glorious purpose—or, more accurately, the spawn of an angel and a demon—is held up alongside The Watchmen (which I have unsuccessfully tried to finish twice) and The Sandman (haven’t read that one either) as comics reading requirement.

While I don’t feel all that bad about missing out on The Watchmen or The Sandman, as a native-born Texas, Preacher did give me some pause. Besides the setting of East Texas, what little I did know of Preacher was its status as a parade of blasphemy and gratuitous violence that is largely directed at institutionalized Christianity. As a kid who grew up in a town filled to the brim with Christian evangelicals telling me I was going to hell for asking the questions that I did, I could get on board with a comic book like this! I agreed to read the entire 75-issue series, in preparation for the AMC television series premiere.

Spoiler Warning: This article contains many spoilers for Preacher.

Published by Vertigo, Preacher originally ran from 1996-2001. The story is: Jesse Custer, an East Texan, is possessed by a Christian deity called Genesis that gives him god-like powers, and the Big Guy Upstairs is feeling threatened by all this hullabaloo. Jesse ain’t havin’ that, so he sets out on a road-trip-style adventure across the United States to track down the The Holy Bearded One. On his journey, he is often accompanied by Cassidy, an Irish vampire, and Tulip, Jesse’s gun-loving girlfriend. Along the way they encounter a myriad of characters, ranging from the tragic and grotesque to the tragicomedic and grotesque.

So, what did this Texas gal with her own ax to grind against Christian evangelicalism think of all this?

I liked it and hated it, which seems apropos to a series like Preacher, a story with a distaste for the sacred that is about as subtle as Donald Trump’s racism. The raging teenager in me was licking her lips and nodding along, “Yeah, that’s right, burn that shit to the ground!” The comics scholar in me appreciated the fully realized mythos and how the themes, stories, and characters were interwoven together. The literary nerd enjoyed and appreciated the creative overlap of the Western genre and the Southern Gothic. It’s good stuff, it’s smart, but it’s also an incredible letdown that reflects its age. Most of all, I loved Tulip.

I hated Preacher, because it indulges in wanking itself off to its own sense of “gender progressiveness” and then wallowing in its ejaculations. Reading along, I would find myself enjoying the complex and insightful conversations between Jesse and Tulip about, for example, Jesse’s sexist treatment of Tulip. See, Jesse is our romantic hero with some high falutin’ ideals about how men should treat women. Tulip calls him on his bullshit, but she’s also in a bit of a swoon over his romanticized cowboy ideals, as well as his tight white pants, and it’s this contradiction that concerns me the most when bringing Preacher the late 90s comic book to 2016 television.

Comic Book Tulip

Tulip tugs at my heart. She’s lipstick and guns, and I ain’t talkin’ a five round pistol. Tulip likes her guns capable of throwing back a grizzly bear in a single shot. She doesn’t take any shit. She’s the Maureen O’Hara to Jesse’s John Wayne; a tough, smart, and capable white woman who stands out from all the other white women. Scholar Michael Grimshaw in his article “Preacher, of the Death of God in Pictures” sums up this type of female character trope as: “Tulip draws on a pulp culture tradition of sexualized action-women, from Wonder Woman to Charlie’s Angels and Tank Girl on to the virtual heroine of Lara Croft of Tomb Raider.”

But for me, and the many female readers who have expressed a love for Tulip, Tulip is this and more. Tulip is a type of broad; and while broad can be a derisive term, a broad can also be a trickster figure, operating within and outside of traditional gender norms. A good example of this is one of my favorite scenes in Preacher. During a look into Tulip’s backstory: we witness a troubling and lonely childhood experience that a lot of women like Tulip know all too well. Tulip is in school, trying to find some other kids to play with. She first finds a group of girls, but they don’t want to hang out with her because she doesn’t act female enough. Rejected, Tulip finds the boys, but they don’t want to play with her either on account of her being female. There are moments like these in Preacher that capture the harmfulness of gender essentialism. It’s exciting to witness in a series that is mostly a sausage fest, and it’s relatable for women who know the hypocrisy of being celebrated for being into traditionally male activities and simultaneously rejected for said interests.

More fist-pumping moments happen when Tulip is hanging out with her best friend Amy. The two are quite a pair, and dolled up and out and about, I can imagine these two as “Woo girls” who brawl like my beloved Rat Queens. At one point, Tulip rescues Amy from a near rape by driving a truck through a wall; their guns and antics empowering within the context of a patriarchal society where you use the master’s tools to tear down the master’s house. That’s not the only way to fight the patriarchy, but like Jesse who is using his godly gift to call out the Christian god, Tulip is tearing through patriarchal institutions with guns and fast cars.

However, as cool as these moments are, they are disappointingly fleeting, and ultimately undermined by two egregious plot points.

The first one occurs during the time that Jesse is believed to be dead. Cassidy, who has been pining over Tulip since the beginning of the series, provides a grieving Tulip with a steady supply of drugs to keep her incapacitated so he can have sex with her. The word rape is never used, and when Tulip eventually comes to and ditches the drugs, she does call out Cassidy, but she also assumes responsibility for what happened. This isn’t entirely at odds with Tulip’s characterization as one who pushes back against victimization, but within a larger patriarchal culture where rape victims are blamed for being raped, I threw my trade paperback across the room. Further, Cassidy’s treatment of Tulip ends up being narratively framed as not an appalling violation of Tulip’s grief, but instead becomes about Cassidy fucking Jesse’s girl, when Cassidy and Jesse go face-to-face in a final showdown at the end of the series.

In this final showdown, Cassidy agrees at Jesse’s behest to meet him in San Antonio in front of the Alamo. Jesse is infuriated and disgusted with his former friend, and Cassidy is wallowing in self-loathing. Cassidy confesses his sins to the good Preacher, culminating in his “worst” sin of all: Hitting a woman. So, despite the long list of crimes Cassidy has committed, this is the worst?

Now, “never hit a woman” is a common trope that is presented as noble and just plain polite as opposed to sexist. TVTropes.org effectively sums it up as such:

“Since a true hero never uses his strength against the weak, and all women are supposedly weak compared to him, it follows that a hero must never use physical violence against any woman, ever.”

This is frustrating as hell. It is what Tulip has been fighting against all along: sexism shrouded in overtures of romanticism. Despite the conversations and arguments with Jesse before where Tulip voices her opinions, there is no Tulip around to speak up in this scene. Thus, this culminating exchange that is crucial to the overall narrative is ultimately about Cassidy’s guilt and his bond with Jesse.

This gives me pause for Television Tulip in 2016.

Television Tulip in 2016

When Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen took on producing Preacher for AMC, they were already self-admitted fans of the comic. This was immediately a disconcerting sign for me. Fan creations for mainstream media can be spectacular (see the new Star Wars), but they can also be complete flops (see Transformers). This usually happens when producers and/or showrunners are so beholden to the source material that they sacrifice acknowledging the differences of storytelling across mediums and resist updating said story 15 years after it ended.

Not all hope is lost though. Goldberg and Rogen brought on Sam Catlin of Breaking Bad, who had not previously read the comic. They also consulted with Ennis, who encouraged them to not be beholden to the comic. Having this sort of leeway from a creator can be a boon for creative license. Additionally, the team, reportedly, cast Tulip first, and they cast Ruth Negga, an Irish-Ethiopian actress.

In the comic, Tulip is a leggy, busty blonde white woman, and considering the all-too-frequent outcry over race-bending characters that were originally white (Michael B. Jordan as Johnny Storm in Fantastic Four) or assumed to be white (see the racist comments over the casting of Amandla Stenberg as Rue in The Hunger Games), this is a bold move on the part of the creators. It’s one I applaud, especially in consideration of the continued lack of women of color representation in geek media.

But, I also have some concerns about this bold move.

Place and regionality are central themes in Preacher, which is why I jumped on board for reading it in the first place. Jesse’s Southerness is an amalgamation of Southern gentility and Western rugged individualism that is particular to East Texas. Cassidy’s Irishness, and thus foreignness, is front and center, and the comic is written by an Irishman enamored and simultaneously critical of the American Dream. The experience of a biracial woman in the American South is a very particular experience and one that should not be ignored.

This means two things: Preacher the show has an incredible opportunity to explore the intersections of place and race in the characterization and experiences of Tulip, and it also has a high likelihood of collapsing Television Tulip’s complex ethnicity into a singular experience as imagined by a creative team that is mostly white and male. This absence of women writers and people of color on the writing credits also does not bough well for Tulip’s characterization; in fact, this absence lends further credence to my concern that regressive attitudes towards gender and race will be shrouded as progressive, via romanticism and the Strong Women Character™.

Like Cassidy and Jesse, Tulip’s own place and identity should be explored in compelling ways—she deserves that. She deserves to be central to the story in an ensemble cast, not just Jesse’s girlfriend, nor the object over which Jesse and Cassidy tussle. I want more for Tulip in 2016, and I want even more for a biracial Tulip in 2016.

What about you, readers? Are you a Preacher fan—can you relate to parts of its DNA, like I can? If you’ve watched the first episode by now, what did you think of Tulip’s representation in the first episode? Share your thoughts and insights in the comments section.