It wasn’t long after my first tentative steps into learning about East Asian pop culture that I came across an inescapable and fascinating part of the entertainment industry: Idol scandals. They range from disrespect and rude remarks to full-on sex scandals and everything in between. Some idols emerge unscathed, the attention only fueling their popularity. Others disappear under the weight of the accusations, true or not.

Idols are, after all, multi million-dollar commodities, and they are considered investments by the agencies that build their careers. But what do these idol scandals say about the people involved, and how much do they affect the way artists and their private lives are viewed by the public?

1. Idol contracts are nigh-unbreakable.

Signing a contract to become an idol—or more realistically, to work towards becoming an idol with no guarantee of ever actually debuting as one—is about as simple and pain-free as walking on a floor of Legos—on fire.

Many idols sign contracts with their agencies when they are very young. Companies recruit tweens and teens into their rosters, building the perfect idols from the ground up. Idol recruits are trained in singing, dancing, and acting and in competition with each other from the minute they enter the agency. SM Entertainment, JYP Entertainment, Johnny & Associates, Stardust Promotion, and their ilk invest heavily in their recruits. It isn’t surprising that an artist might feel a very deep obligation to their agencies to succeed.

For those who have attempted escape, long legal battles await. Dong Bang Shin Ki, or DBSK, began a court face-off with SM Entertainment regarding their contract terms. One particular point of contention was how little the group members actually earned, given how profitable their brand was for the company. Fellow SM Entertainment recruit Han Geng filed for contract termination in 2009, citing the length of the contract (13 years), underpayment of salary, and a grueling schedule that led to illnesses. Former EXO-M member Kris also decided to end his contract with SM, though he departed with a clear plan for continuing his career in China without the agency. And earlier this year, Japanese pop group SMAP were embroiled in drama over their alleged attempt to leave Johnny & Associates to follow their manager out of the company.

Google their names and their legal troubles are among some of the first results. It’s a testament to how deeply tangled idol careers are with their agencies and how difficult it is to break out of the music industry.

2. Penlights are both signs of affection and gavels of judgment.

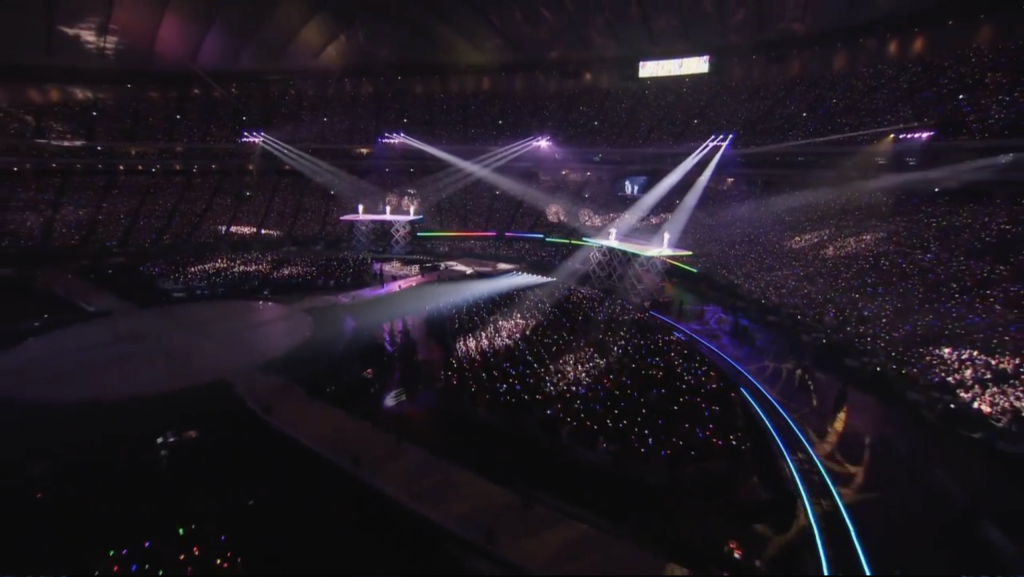

An idol concert wouldn’t be complete without the sea of penlights illuminating the venue, and in some cases, lighting up in time to the songs themselves. For Japanese fans, penlights are as essential as the uchiwa, or fan, and Korean pop idol groups are often assigned their own penlight colour, distinguishing them from each other.

But penlights aren’t just used for bopping along to the music and feeling like you’re part of a fanbase. No, fans have also used their penlights as a not-so-subtle way of showing disapproval and hatred towards particular groups.

How could a mini-flashlight signal anger towards an artist? You turn them off. It’s called a “black ocean,” and it requires a pretty strong commitment to the cause and coordination among fans of a rival group to carry out.

Exhibit A: An Arashi concert, penlights bright against the spotlights and stage lights.

Exhibit B: A recent black ocean, performed against Seventeen at the MAMA Awards.

For Korean idol fans, a black ocean is a succinct statement, a dismissal of the idol group and their performance. It’s the ultimate cold shoulder: Your efforts are not worth even a single light shining for you in the darkness.

3. Racism and discrimination aren’t a surprise.

The desire and value placed on white skin and the “right” heritage isn’t limited to the U.S. and Canada. Idols with pale skin find themselves in the spotlight far more often than those who might be even a shade or two darker. Yuri of SNSD/Girls’ Generation is referred to as the “black pearl” for her skin color, something I personally had not noticed until it was pointed out over and over again. Even then, the difference is negligible, and it’s certainly not something that should be a talking point for any reason.

Bottom (L-R): Sooyoung, Tiffany, Hyoyeon

Blackface is also unfortunately more common than one might think. Last year, female idol group Momoiro Clover Z appeared in blackface with comedians Rats & Star just before filming a variety show. The image is more than cringeworthy: It’s a reminder that even in 2015, this is still a thing that happens, and happens with the approval of multiple cultural authorities.

Why Japan needs to have a conversation on racism (1) https://t.co/o07lYKoYri Preview of a TV show airing next month. pic.twitter.com/KDoDPVz6xJ

— Hiroko Tabuchi (@HirokoTabuchi) February 12, 2015

4. Girl groups have an inescapable obligation to their core fanbase: Men.

Remember that airtight contract our idol groups sign? Among the various things that aspiring idols end up promising away is their own ability to be in any relationship that does not cater to their fans. No-dating clauses are common, with some companies going so far as to declare particular talents and/or agencies off-limits to their artists. Consequences of flouting this rule include termination of endorsement contracts, public shaming, and in some cases, the end of your career as you know it. That is, if you’re a female idol.

Male idols are subject to these clauses too, but it’s the girls who are pressured to be as available as possible to their male fanbases, without ever actually making themselves available. Maintaining the fantasy is key to their success, as a female idol with a boyfriend is a female idol that male fans can’t ever have, no matter how many CDs they buy or concerts they attend.

AKB48 is an excellent example of this phenomenon, and by excellent, I mean it’s actually awful how these young women are being treated. Tickets to handshake events and other opportunities to encounter the girls are given away in CDs and DVDs, but not every item carries them, driving sales more effectively than critical acclaim. Male fans buy these CDs in bulk to collect passes to these events and to vote for their favourite members of AKB48 to advance through the ranks and become the front-women for the group. This technique draws the male fans in and promises them the loyalty of their favourite girls.

Former idol Minami Minegeshi learned first-hand what it means to break that unspoken agreement. When she was caught having a boyfriend, her work with AKB48 was halted, and she was demoted to a trainee team for breaking the rules. She later uploaded a video displaying her shaved head, apologizing for the “thoughtless and immature” decision she’d made. Some fans defended her, but the agency had spoken, and her career was over.

5. Women will always bear the brunt of any scandal.

Minami Minegeshi was soundly dismissed for daring to date a boy. But her story isn’t new or surprising for many female artists.

2016 started with the worst of times for Japanese TV personality Becky (Rebecca Eri Ray Vaughn), as her affair with Enon Kawatani was revealed by tabloid Shunkan Bunshun. Kawatani’s six-month marriage to another woman seemed to have barely registered with him and Becky. The fallout was swift and one-sided. Becky’s endorsement contracts disappeared one by one, and her regular appearances on variety shows were culled down to nothing by the time February rolled around.

While Becky isn’t an idol, she—like most young female entertainers in Japan—was held to moral standards that were broken when her affair was revealed to the public. Her career had been built on the image of the nice girl-next-door, a charismatic young woman who was flirty and engaging, but who still stayed chaste in the public eye. This illusion was shattered.

And yet Enon Kawatani remains a presence in the Japanese music industry, his band taking a small break to deal with the scandal’s aftermath, but it would not surprise me one bit if a comeback wasn’t already in the works. His career has slowed down, perhaps, but it has not been brought to a complete stop like Becky’s.

In 2015, Korean actress Clara was forced to put her career on pause to file for contract termination from her agency, citing sexual harassment by the CEO. Over ten months, her character and moral fortitude was questioned, and she was accused of trying to blackmail the CEO. Fans and the general public alike seemed to flip-flop between believing Clara and supporting the CEO, but the personal attacks on Clara continued until the lawsuit was settled in September. The message is clear: Women in entertainment are expected to be perfect, lily-white goddesses, and if they are unable to maintain that reputation, they are worth nothing.

While I certainly don’t intend to paint the entire Asian entertainment industry with a damning brush, these particular observations aren’t one-off events. They have happened, and continue to happen, across the different countries. They set precedents and confirm to society that this is the status quo—unbreakable, inevitable, and unstoppable. The treatment of women in entertainment is especially appalling, and it says a lot about how societies all over the world still have a long way to go before real equality is possible.

I don’t think we’ll see significant changes in my lifetime, but it does make me wonder how much these business practices have influenced cultures and economies and people. Would boycotts have any effect? It’s hard to say. How would protests affect an industry that continues to pump out new groups every month from their ever-lasting scores of hopeful young stars? How deeply would the Korean or Japanese economy suffer if the idol industry as we know it today collapsed? Does the work that these groups do, through their blood, sweat, and tears, and their success make their personal sacrifices worth it? I expect the answer is just about as complicated and grueling as the process of creating a new superstar.