Welcome to An Adventure in Small Games, a monthly series focused on games that cost less than $20, ideally less than $10. In this series Eve Golden Woods will focus on the indie game and what it has to offer the world of gaming. There will be spoilers. This month Eve takes a look at Kitty Horrorshow’s games.

Horror is a strange thing. Too often we collapse it into fear and terror and discomfort. And all of those things can build into horror, or give it a more potent effect, but none of them are at the core of horror. Horror is the sickening feeling of confronting things that are dark and unresolvable, violence and nightmare given form. Great horror, like Silent Hill 2, Uzumaki by Junji Ito, or the comics of Emily Carroll, is unnerving because it forces us to explore worlds in which we are powerless and uncertain; in which the structured rules of our existence fall away and we are left without guides; in which we do or become things that we dread becoming. This month, then, I present you with a triptych: three horror games by Kitty Horrorshow, three paths into worlds with rules very different to our own.

Rain, House, Eternity

Rain, House, Eternity

This game has two endings and two beginnings. So promises the game’s description. There is a tension here, then, an uncertainty of linear time, a space in which what is and what must be are nebulous and changeable.

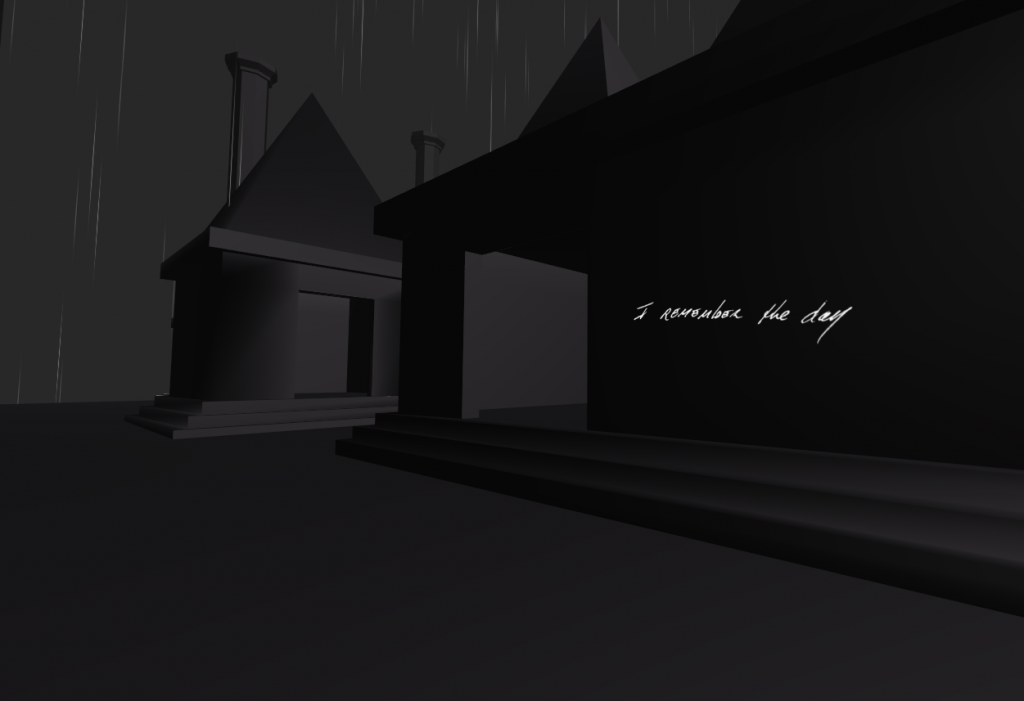

The game opens in darkness and rain. The world is bleak, with leafless trees and bare hills unrolling through the gloom. Strange and uncertain wandering leads you to an impossible structure, a huge series of steps that open onto a platform surrounded by rising concentric rings. The architecture in this game is deliberately impossible. Each space opens up as a floating platform, suspended in the void, with only the falling rain to remind you of gravity. Though each level seems full of echoes of purpose, whether that means open squares and plazas, houses, or parks, there is an alien sense of isolation to them, a minimality which implies that they have never been used and never will be.

The story is told in two ways, though it appears to always be the same voice speaking. On each level you find purple crystals which cause scrawled handwriting to appear, flung across the sides of buildings or hanging in the air. These short, terse statements seem written in the moment, giving cry to the emotions of the being who speaks to you. As you move from level to level they speak at greater length, telling you something of the nature of your journey and what awaits you at the end.

One of the most elegant aspects of Rain, House, Eternity is the camera perspective. As the game plays out you begin to realise that your eye level is lower than you would expect, that you are smaller than you had imagined. The story confirms that you are a child, but the use of the camera to reinforce this is extremely effective. It lends a potency to the words of the one who speaks to you, and adds an extra chill when you understand what you are supposed to do.

One of the most elegant aspects of Rain, House, Eternity is the camera perspective. As the game plays out you begin to realise that your eye level is lower than you would expect, that you are smaller than you had imagined. The story confirms that you are a child, but the use of the camera to reinforce this is extremely effective. It lends a potency to the words of the one who speaks to you, and adds an extra chill when you understand what you are supposed to do.

Of all three games, I think Rain, House, Memory is the kindest and least fearful. There is horror here, and pain and grief, but there is also healing and reward. It is a game that inhabits dark shadows but also bright light. It doesn’t ask you to jump or to cower. It is full of grief and kindness, and moments of beauty that are more painful for being so rare. Though it does not shy away from the brutality that societies may impose on their vulnerable members, it also offers the hope of transcendence.

CHYRZA

CHYRZA

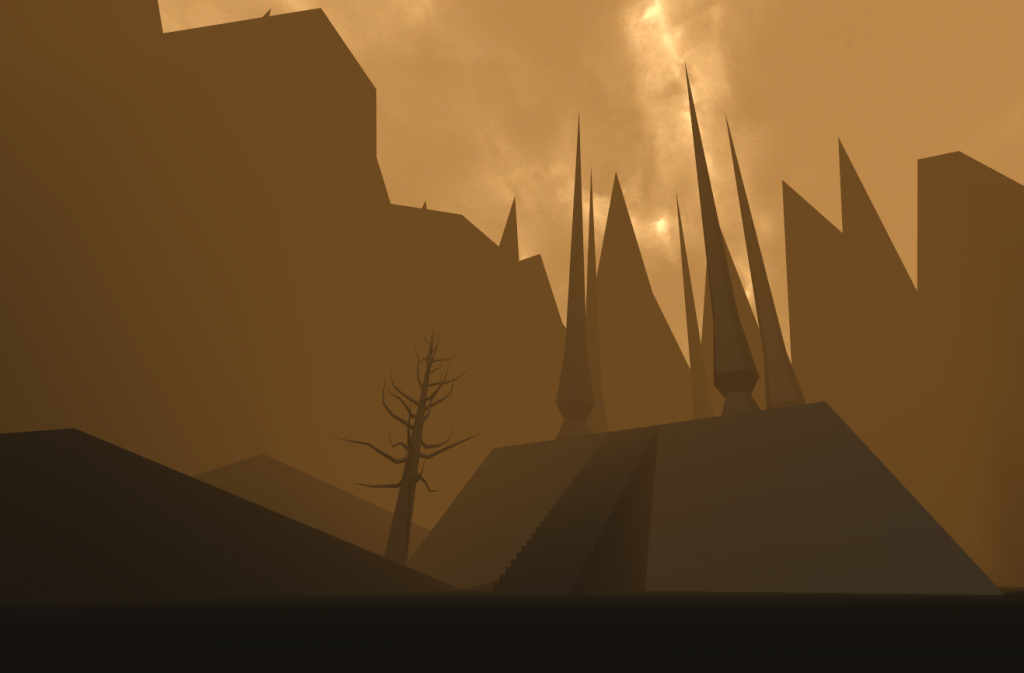

Horror games so often collapse darkness and fear. Shadows, tunnels, caves and night become spaces of uncertainty, voids of concrete meaning where the doubts and monsters of our subconscious can rise bubbling to the surface. CHYRZA, on the other hand, is a game set in the desert, full of warm yellows and blazing sunlight. That makes it no less horrifying.

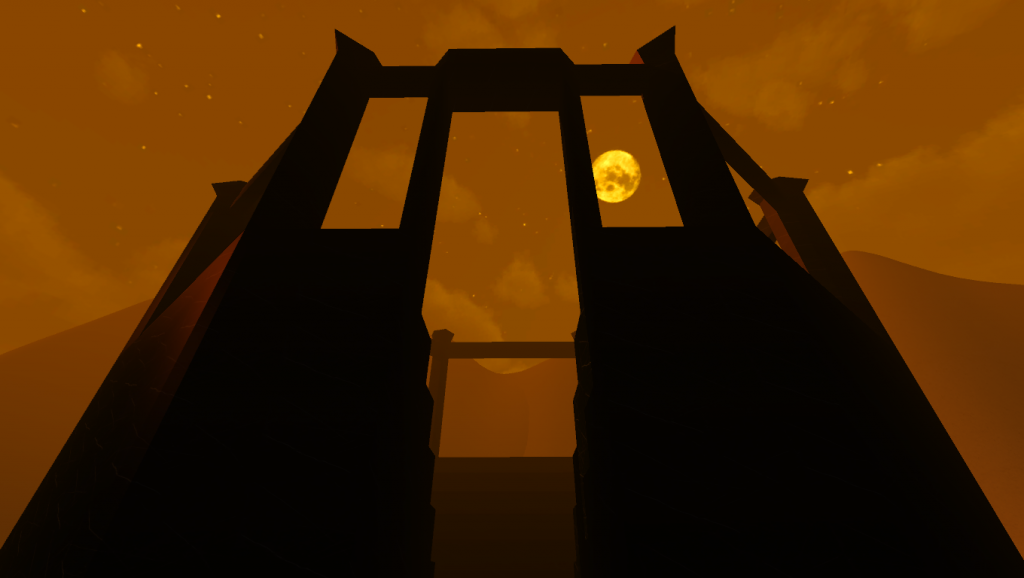

Architecture is present here, too. Strange, impossible structures loom out of the desert. Each of them conceals a green stone that activates a voiceover, and as you move from one to the other the story slowly unwinds in a visceral tangle of narrative.

This is certainly the most visceral of the three games. The use of a voice, with all its tremors and inflections, its ability to convey information in a carefully paced way, gives the game an extra edge of horror. Particularly at the end of the game, the shared connection of a human voice reaching out to you makes the climax of the game much more satisfying.

Themes of intrusion and transformation run deeply through CHYRZA, as they do through Rain, House, Eternity. This is a game about humanity and inhumanity, and how thin the line between the two really is. The buildings of the game speak to this, the rough stone walls of the village huts, in their strange organic configurations sharply contrasted with the sleek alien lines of the other structures. The black pyramid, centre of the horror, stands out against the soft undulations of the mountains behind it.

Given that I prefer not to give away too much of the games I review, especially since horror games often rely on the moment of revelation to make their narratives even more uncomfortable and unnerving, it’s hard to talk about what I liked most in CHYRZA: the ending. Let me say only, then, that I think the ending of this game is chillingly fascinating. It creeps up on you, and something that seems like an odd choice the first time you play the game becomes a moment of horror when you replay it and realise what it implies.

Dust City

Dust City

Strange buildings rise out of a grey plain. The air is thick and yellow, heavy as fog and swallowing the distance. From the windows of the buildings a dim green light gleams. This is the starting point of Dust City, and, in a way that is reminiscent of Myst, this one central area leads to many separate realms, each one with a different style and aesthetic. There’s a balmy island where coins float above green grass and white pillars rise out of the ground or float around it. Another area is pure black, dark towers and moving platforms carved out of lightless rock, rising from a purple sea.

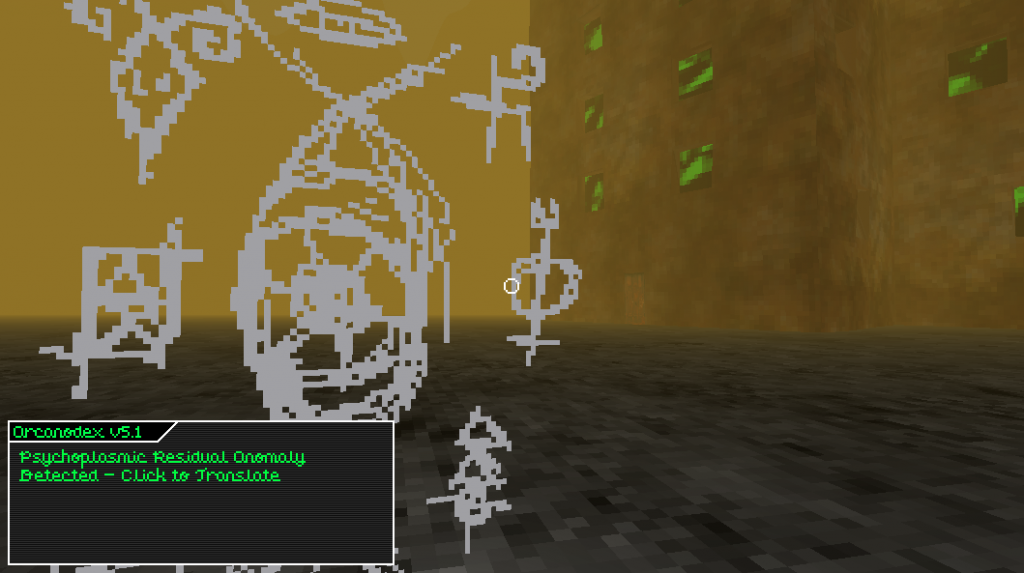

You have been sent to explore this area and discover its secrets with the help of an Arcanodex, a small machine that translates the many strange artifacts of the ruined world around you. Strange white gylphs float in the air, giving voice to the sometimes mundane and sometimes impossible concerns of the world’s lost inhabitants. And then there are the artifacts. Using the Arcanodex on them will give you a password which unlocks zip files included in the game folder. It’s a strange and novel way of interacting with the game. You must step outside the program to achieve “completion”. But the rewards are fascinating, a glimpse into fragments of thought. You can try to tie them to the narrative of the game itself or see them as representative of Kitty Horrorshow’s own thoughts, but either way they expand the game’s universe, forcing you to think about what defines the realm of the game’s universe.

The game takes many of its cues from games like Doom, Half-Life, and Myst, but its focus is not on shooting, roleplay or puzzle-solving. Rather it seeks to create a space that stretches the limits of the impossible, in which unknown and strange things have come to pass. You stand as a witness to apocalyptic cataclysm, though what it has left is unclear.

Kitty Horrorshow’s games have many things in common. Impossible architecture is crucial in all of them. They are games obsessed with structure, with the imposition on and definition of space. How does a tower define the world? What happens when the rules we expect to be obeyed are broken? How then do we navigate and what then do we understand? Visually, there are also many connections, both in the low-poly art style and the deliberate use of large pixels and rough textures. There is no desire for fidelity or “realism” in these landscapes, which rather seek to take some of the familiar elements of video game aesthetics and exploit their ability to distort and unnerve a player.

Kitty Horrorshow’s games have many things in common. Impossible architecture is crucial in all of them. They are games obsessed with structure, with the imposition on and definition of space. How does a tower define the world? What happens when the rules we expect to be obeyed are broken? How then do we navigate and what then do we understand? Visually, there are also many connections, both in the low-poly art style and the deliberate use of large pixels and rough textures. There is no desire for fidelity or “realism” in these landscapes, which rather seek to take some of the familiar elements of video game aesthetics and exploit their ability to distort and unnerve a player.

Thematically, sacrifice, transformation and rebirth echo like a cry from one to the other. People are not what they seem. They can be transformed by external sources, or choose to remake themselves. The landscape too may change around you, buckling under its own weight until it becomes something else, something impossible. Endings are inevitable, but they are not to be trusted.

Above all, what I find so fascinating about her games is that they explore horror without fear. We collapse the two so frequently that it can seem impossible to separate them, but Kitty Horrorshow manages it. Her games give you the space to confront things that are awful and impossible and unnerving, or to use a more deliberate word, uncanny, without demanding that you tremble and cower. There are moments of fear, of course, but there are also moments of humour and kindness and grief. Rather than detracting from the horror of her worlds, they make it more potent, laying bare that human emotions are felt clearly and cleanly even when drowning under the weight of our own nightmares. Her games imagine worlds both bigger and smaller than our own, in which we wander without context. Like dreams, we must accept them on their own terms and let them play themselves out, in the hopes of learning from them a little more about who we ourselves are.