Disclaimer: This post contains mild spoilers for Logan.

“It’s just a story.” How many times have you heard these words? Did you hear them as a child, when you found solace in a fantastical world? As a young person who discovers a book that makes you feel seen? Maybe as an adult who adores comic books, but expresses sadness at the way you are constantly exploited within or written out of this thing that you love?

Storytelling has for millennia been a way of sharing and documenting human history. From Egyptian hieroglyphs to the “Greatest Story Ever Told” in the Bible, from The Iliad to Grimms’ Fairy Tales and Aesop’s Fables, the world has always been full of stories that attempt teach us about who we are, where we came from, and what those who were here before us achieved or attempted to. So when did the narrative of stories as “nothing more” than entertainment become the most accepted one?

Growing up as an avid reader and comic book fan, I was often told that I became too invested in the lives of people who had never existed. As a child I fell in love with imaginary characters who helped me learn how to feel for the people I interacted with on an everyday basis. The stories that I read often felt more real than the world I inhabited and gave me a fascination for the importance of storytelling as a tool for existence that still fuels me to this day.

Watching Logan, the newest–and possibly final–outing for Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine, was the first time that I’d truly seen the idea of comics as mythology and human storytelling explored outside of my own head or conversations with friends. The recognition of the power and impact that these stories can have was a revelation for those who I watched it with. We spent hours afterwards discussing the possible ramifications of comics as historical documents and what this would mean in the real world.

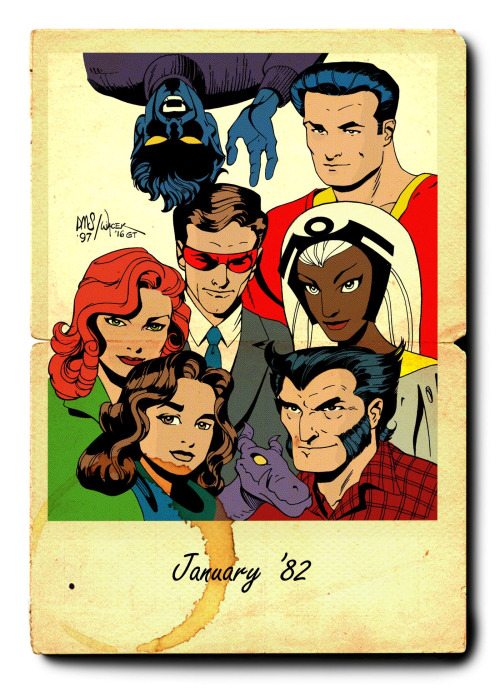

I should probably give a little context to Logan‘s place and importance in the world. There was once a time (it was the 90s) when if you wanted to watch your favourite A-List caped men in feature length fashion your only real options were a few inconsistent Batman adventures, a rubber-eared Captain America on a bike, or a lost Roger Corman gem about the first family of comics, the Fantastic Four. Now superheroes are synonymous with the summer blockbuster, record breaking opening weekends, and sprawling interconnected universes which sometimes take decades to build and often feel like they take even longer to decipher.

Since 2008 and the release of The Dark Knight and Iron Man (and to a lesser extent the early 00s with FOX’s X-Men franchise and Sony’s Spider-Man movies), that world no longer exists. Superhero films are abundant, whether you want to watch a film about a grumpy alien with a messiah complex or one about four men who inexplicably don’t allow the female scientist in their team to join them on their illicit drunken space expedition. This year alone, there are seven superhero movies being released and there’s no end in sight to the increasingly dark and gritty men-in-tights movies that fill our multiplexes. With over almost a decade of superhero dominance at the box office, it’s unsurprising that these films often vary in quality. Some are wonderful, many are average, and some are awful.

One of the most prolific men in superhero films is Wolverine. Logan. James Howlett. A man who was once in over 200 ongoing series from Marvel. The lone wolf to end all lone wolves, and the man who became the face of FOX’s X-Men franchise. Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine has appeared in nine movies as everyone’s favourite Canadian mutant (sorry, Wade). These films have spanned over fifteen years, are almost unbearably inconsistent, and FOX’s struggle to bring a recognizable and authentic version of one of the most beloved X-Men to the big screen has long been a sore point for X-fans. Then came Logan.

Taking some (extremely) loose direction from Steve McNiven and Mark Millar’s Old Man Logan–he’s old, it’s set in a depressing future, and we’re calling him Logan again–the film finds Wolverine in 2029, a near future in which mutants are all but extinct and our titular (anti)hero makes ends meet as a very buff and haggard looking limo driver. The Logan that we meet is a man out of time, no longer the outcast/sometimes leader of the X-Men but an old, sad, and violent man who’s introduced to us by murdering a bunch of young men who try to steal his limo.

The world of Logan is vast yet suffocating. Border patrols are ever present and a roaming armed militia of mutant hunters called Reavers scour the barren landscape. This is a version of a world far away from FOX’s clean-cut X-Men universe and much closer to ours, a world which punishes those who are different, eradicates those of whom they are afraid, and brings out the worst in pretty much everyone.

Though Logan is presenting a new, nuanced, and wonderfully authentic world, dark and gritty comic book movies are hardly original. The now iconic and game changing Dark Knight trilogy by Christopher Nolan completely altered the way that studios competing with Marvel and their primary coloured coherent universe, approached their superhero movies. FOX’s much maligned Fantastic Four reboot was so bleak that you could taste the sadness on your tongue, and the current DCEU suffers from the leftovers of this increasingly stale trend. Not only does Logan utilize its R rating and adult nature, but it does something no one has really done before: it acknowledges the comics it is based on.

The notion of a shared universe is one that’s now synonymous with comic book movies after the immense and unforeseeable success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Though all of the cohesion thus far has only been within superhero films themselves, not only does Wolverine acknowledge that the comics that we know and love exist in Logan, but the film also creates the notion that maybe the books that we know and love are actually a sanitized, false retelling of the true lives that the X-Men have lived.

If this is the case, maybe all of the X-Men movies we’ve seen so far has been a part of this sanitized rewriting of mutant history? This small, almost throw away moment woven into Logan has huge implications. If the comics are clean cut versions of a brutal truth–almost a propaganda tool–then maybe the films have been too? That would explain away the simple, often lacking representation of Wolverine up until this moment. The absence of death, blood, and violence in every version we’ve seen of him. Maybe Logan is the first real glimpse into the realities of mutant life that we’ve ever been given.

The idea of storytelling as legacy and a form of survival is one that runs through the film. The fantasy of freedom and a better life is intrinsically connected with the brutal reality that the film and its characters inhabit. Mutants are hunted and tortured. Visceral videos capture the experiments enacted on the young children who have been born only to be weapons. All the while, nurses tell those youngsters the stories of Eden, a place written about in one of the X-Men comics included in the film. The sanitized, fake stories become more real to the the children than the super-powered team of mutants ever were.

Conceptually, there is something so subtly profound about the exploration of art as truth, stories as hope, and creating a reality of your own as a way of escaping the one that you are born into. The film takes this one step further with the group of mutant children building Eden themselves from the pages of the comics they read. Creating a reality out of fiction and making something tangible out of ideas that never had a physical form, until this group of people needed a home a safe place and took one from the only place that they’d felt safe before: their own fantasies.

So, if we are to believe in the power of storytelling and the importance of sharing stories as a way of recording our history, then there is surely a responsibility around how we document those things. I’ll never forget seeing Mike Carey speak at a comics writers class, and he told the story of a conversation that he’d had where he realised that with thousands of issues and decades of coherent stories, X-Men was one of the largest and most in-depth examples of human storytelling in recorded history.

This assertion blew my mind and helped me see comics in a completely new way. Though I’ve always believed in the responsibility of a writer–and searched for inclusivity and progressive thought within my reading–this idea of comics as a form of record took it to an entirely new level. These stories could have a true legacy, and the often trite, but ultimately well-meaning societal reflections within them may hundreds of years down the line be taken as true representations of our time.

Comics have often striven to tell tales that matter to people at the time in which they’re telling them, from X-Men’s (incredibly basic) civil rights analogue to the world’s most famous immigrant Superman. From Captain America punching Nazis to the Superhero Registration Act as a twisted reflection of the Patriot Act. There’s a long and storied history of comics attempting to tell parables that matter, which is why it can be painful when creators act as if the books they write are nothing but disposable, forgettable stories.

The two ends of this spectrum–of mainstream big two comics as some kind of imperfect historical record–are illustrated in two recent books. One is the ongoing Captain America book in which Steve Rogers is now (and maybe always has been) a Nazi. The book upset many readers when it first appeared, as not only was Cap originally created specifically to punch Nazis, but his creators were Jewish. And, of course, many readers are. This erasure of half a century of history shows an astounding lack of interest in the character or book’s legacy. Imagine for a minute that a century from now aliens found an entire run of Captain America. Not only would they be hugely confused, but once they reached the comics of 2016 they would likely be left with the impression that Cap’s lasting legacy is one of fascism and hate rather than the freedom and progression that he was meant to represent.

At the other end is Michael Walsh and Max Bemis’ Worst X-Man Ever. On the surface the book tells the overdone story of one young boy who discovers that he’s unique. That boy, Bailey, is special as his powers are ultimately useless unless he wishes to kill himself. That in itself is slightly subversive, but the thing that blew my mind with this book is how the hero is actually a young, black woman named Miranda, the most powerful mutant who has ever lived. This black teenage girl has spent lifetimes changing history so the good guys always win without ever getting credit. The honest reflection of the uncredited emotional and physical labour of black women that has shaped the world we live in, throughout history to this day, is the kind of story that we need to record and make sure to tell the next generation.

There is a magic in storytelling, a power in words, and Logan crafts a world that turns that power into reality. It delves into the most base part of why we read comic books–to escape–and crafts something moving and memorable from it. I suppose what I’m saying is think about the stories you tell, what they mean, and why you think they should be told because someday a group of lost, hopeful, and incredible young people may build a new world on the foundations of words you left behind.