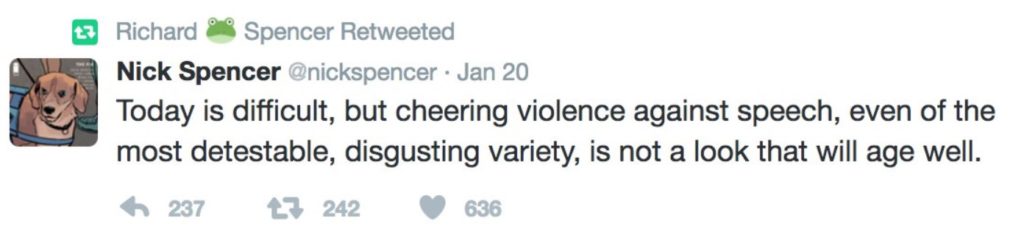

January has seen the writer of Captain America advocating for the bodily integrity of, and being retweeted by, neo-Nazi Richard Spencer. Like a lot of awful moments in the past year, there is a temptation to confuse our horror with shock. We want to ask, “How could this have happened?” But as many Cap fans have seen, this is part of a long trajectory for Nick Spencer. This moment stems from his inadequacies as a writer and a public figure.

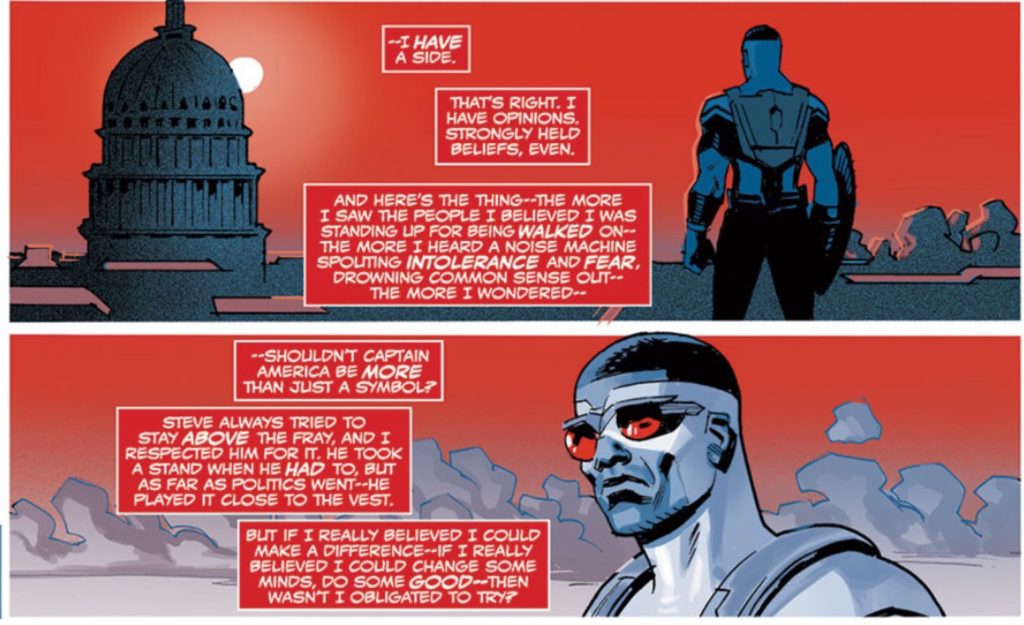

The problems begin far earlier than Spencer’s controversial retcon of Steve Rogers as a secret Nazi (HYDRA-Cap) in Captain America: Steve Rogers #1. In 2015, Spencer launched his first Cap book: Captain America: Sam Wilson #1, in which Sam Wilson (formerly the Falcon), took on the name while Steve was incapacitated. The opening conflict of CA:SW was premised on the idea that until Sam took over, Cap was non-partisan—is; Cap had no political stance. From here, the narrative struggles with whether it’s right that Sam-as-Cap is partisan, insofar as a superhero rescuing border crossers from white terrorists is “partisan.”

The trouble is that this narrative is hinged on the idea that until now, Cap was not political. Apart from being historically untrue, it speaks to a greater failure in recognising that everyone is political. The privilege to believe you can be apolitical is particular to a demographic like Nick Spencer’s. These people are exnominated, a term coined by Roland Barthes to describe how privileged identities are unnamed because they are the norm. The exnominated can believe that their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, bodies, and ideologies are “neutral.” For those of us outside the exnominated—anyone who is “other” in some way—our every action and inaction is, whether we like it or not, read as political. This is how the term “identity politics” arises, because only the non-privileged have a visible “identity,” and its existence is treated as political. Because we have been forced to recognise how our everyday is political, we recognise that the same is true of the exnominated. Not only is Captain America always-already political (come on, his name is “Captain America”), Steve Rogers, like every one of us, is always-already political. To believe otherwise is simply ignorant. It results in a fundamental flaw in the foundation of Spencer’s Captain America books and a lack of social understanding that is necessary for good writing.

To agree to the very premise that someone is apolitical is to validate the power structures that hold these people above others. To believe that one’s privilege is “neutral” is to misidentify oneself in the middle of a political spectrum, with marginalised people at one extreme and, inevitably, those who stand for the elimination of marginalised people at the other. This is how a mistake like HYDRA-Cap happens. First, Spencer asks us to agree to the flawed premise that Sam Wilson is more political than Steve Rogers. To do this, we must ignore Steve’s outspoken leftist leanings since the Silver Age and assume that neutrality is both possible and in-character. If we have agreed in Captain America: Sam Wilson that Steve is “neutral,” Steve’s political identity is hollowed out for a Nazi origin story in Captain America: Steve Rogers #1. Nazism becomes a reasonable part of the spectrum, and it happens because Spencer has built this narrative logic into his work from the beginning.

Spencer’s public response to HYDRA Cap is entirely in line with this. By situating himself as “neutral,” he could call those who criticised his writing “bullies.” The process by which he established Steve as non-partisan was the same setup that divided the “normal” comic fans from the “unreasonable” critics when HYDRA Cap was subsequently revealed to be the overused fake-out trope we all knew he would be. Spencer, after insisting that his retcon would stick, pulled a quick heel-face-turn and hung the joke on his “bullies” forever being critical in the first place. This forged a rift between old school comics fans, who don’t object to Nazis because they know Nazis are just a joke, and the upstart newbies “victimising” Spencer with their politics. To hammer the point home, Spencer lampooned leftist advocates—specifically a young black woman—in Captain America: Sam Wilson #17 as ineffectual, pretentious, even embarrassing terrorists. Part of Sam’s character journey over the last 17 books has been his own drift toward the commendable centrality that Steve no longer occupies, as he searches for Steve’s approval in denouncing those wacky leftist women overreacting.

Readers who objected to the book fell directly into Spencer’s narrative of the left as political and himself as a neutral party. It’s no accident that this dialogue between the old guard of comics fans and new readers fell along gendered lines; we’ve seen spilling from nerd culture into the American election, too. The story that men, no matter how fascist, are reasonable, while women who challenge them are inherently shrill, was the only narrative Spencer told well in 2016. Spencer doesn’t mind metaphorical punching, as long as it’s punching down.

This shows us how, for a long time, Spencer has built this narrative in three stages. First: neutrality as possible. Second: neutrality as reasonable. Third: stances further left than neutrality as unreasonable. His entire tenure as the writer of Cap books has been working to recreate the popular fanboy illusion that superheroes can and should be apolitical. He’s set a scene where activism and criticism are not only wrong: they’re out of character, unheroic, and embarrassing. This long game leads to a point where the man who writes one of culture’s most famous Nazi-punchers advocates for a genocidal neo-Nazi. Now that Richard Spencer has retweeted him, we can see exactly whom the myth of neutrality serves.