This is part two of my account of teaching G. Willow Wilson’s Ms. Marvel to honor students at a large southern university. Part one can be found here.

It’s honors multicultural lit. We have our copies of Ms. Marvel: No Normal in front of us. Not a single student has ever read a comic. Go!

Actually, they took to it very well. The outpouring of comic book movies from Hollywood has made everyone feel, just a bit, that they are a part of this once shunned subculture. They had the proper context with which to understand how a heroic origin story works and to identify what is revolutionary about Kamala Khan’s journey. However, it was not her struggles as a female teenage superhero that intrigued my class, but her place as the first Muslim superhero to headline her own comic.

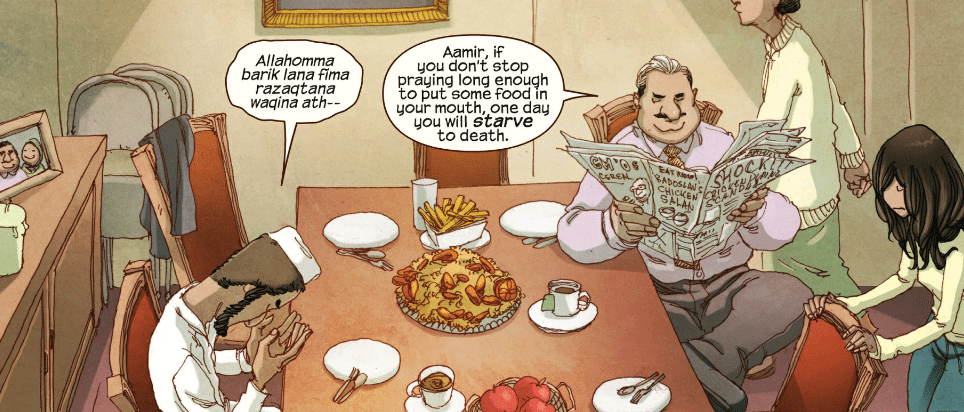

Speaking for the whole class, one student commented that “[b]efore reading [No Normal] I had no idea what life was like for Muslims in the US. I never considered it. If asked, I would have no idea of how to answer.” Unlike with superheroes, my students had no context—Muslim-Americans were more exotic to them then a girl getting morphing powers from an intergalactic mist. Perhaps this is why there were fascinated with the parts of the comic that touched on Kamala’s home life and religion.

Another student said, “I didn’t really care about the superhero plot, but I loved seeing Kamala’s family life. Her parents cared more about her being happy than about her being a traditional Muslim girl. They were no different than my parents, who push me to attend mass and not eat meat on Fridays, but who I know will always have my back.”

As an introduction to reading between the lines and through the gutters, each student was asked to select a panel and perform a close reading based only on graphics. All except two students picked panels that focused on Kamala’s culture. Of particular interest was the relationship between Muslim-American children and their parents. That Nakia, Kamala’s best female friend, insists on wearing a hijab despite her parent’s disapproval and that she looked effortlessly chic while doing it was a revelation. That this same “traditional” Muslim girl skips out on a youth lecture at the mosque, since the screen the women worshiped behind hides her from the imam, gave depth to what had been a one-dimensional character and religion. “Kiki [a nickname for Nakia that she rejects] is playing with the flexibility her religion allows her as a woman,” one student commented. “A man, who seems to have more freedom, would never be able to sneak away without being seen.”

Is this the same flexibility that Kamala and other superheroes gain when they wear masks? To be and not be at the same time? “Maybe” seemed to be the consensus to this question, but it led to another panel of visual interest, that of Kamala in her final superhero outfit. In her converted burkini (an Islamic swimsuit) and her veil flowing behind her like a cape, Kamal’s dusky skin and dark hair is a sharp contrast to her earlier superhero persona, the white and blond beauty of the much admired Carol Danvers, a.k.a. Captain Marvel. “She is more real, more relatable than [Danvers]” was the view of the majority of the class.

So it seems the tall, blond American dream is intimidating to most of us, not just Kamala. While this is unfair to Captain Marvel (and the single blond girl in my class, who is tall and beautiful), it’s also a credit to how well Wilson is able to make Kamala, despite her pakora lunches, her “weird holidays,” and her alien DNA, an all-American hero.

One student confessed that “Ms. Marvel gave me a character that reflected how I felt during a very vulnerable time in my life. I would have never expected to see a piece of myself in a science fiction comic book, but I am thankful that Kamala Khan was able to teach me so much about myself. Thank you to Kamala Khan for reminding me that it is normal to be insecure, but true happiness comes when you learn to love yourself.”

In what is arguably the most visually arresting spread in the comic, Captain Marvel appears to Kamala in a vision, her arms outstretched in imitation of a goddess, speaking in Urdu, and encouraging Kamala to embrace her powers. This mix of American and Muslim imagery is all the more arresting as the Ms. Marvel Kamala has conjured is paraphrasing text from the Quran. This same message of kindness and tolerance is later echoed by Kamal’s parents and her imam. “I learned more about Islam from this comic then I ever have from the news,” commented one student, while another wondered why the media always focuses on the “violence” of Islam.

The second collection of Ms. Marvel, Generation Why, focuses more on Kamala’s place as a young, female superhero. Wolverine is forced to let Kamala both fight for him and physically carry him when he temporarily losses his powers. I love that the oh-so-masculine Wolverine rides piggy back on the awe struck Kamala, who is geeking out over meeting one of her heroes. My students, however, were disappointed in this story line. “She seems more generically a superhero now, less Kamala and more Ms. Marvel,” one student complained. After some probing, the class came to the conclusion that Kamala is more interesting when surrounded by her family and her faith. By far the most liked section in Generation Why was the conversation between Kamala and Sheikh Abdullah.

“Kamala’s religions is what inspires her to be a superhero. Her parents and [Sheikh Abdullah] taught her to think of the greater good, even if it means putting yourself at risk. So Kamala defies her parents and the strictures of her religion in order to follow what they have taught her,” one student observed.

They also lamented the lack of Nakia, who, despite playing such a small part in the comics, was much admired. “Kamala thinks she wanted to be like Zoe [stereotypical popular girl], when really she should want to be more like Kiki—at home with her faith and in her skin.” Nakia was even more liked than Carol Danvers. After explaining the importance of Captain Marvel in portraying a strong, female hero while still being blond and beautiful, the class conceded that she was “all right,” but that her storyline was “typical” when compared to Kamala’s. They liked Kamala for the very reason critics thought she might be rejected.

Could this acceptance of Kamala’s “differences” transcend comics? Despite its problems, comic publishers have shown a willingness to take chances on unconventional (a.k.a. “not white”) heroes. But what about the film industry? I asked my students to propose a film version of Ms. Marvel to the production company of their choice, including financial projections, casting choices, and marketing campaigns. One contingent of students satirized the film industry by developing a big budget movie with a totally white washed cast. Kamala (now called Kristin) is played by a highly sexualized Chloe Moretz with Zack Effron as her sidekick. The second group pitched their movie to “indy” film studios, and proposed keeping the movie as close to the comic as possible. However, their choice of Ariel Winter, whose heritage is Greek, as Kamala was problematic.

Since this was a literature class, I taught Ms. Marvel primarily as I would a novel—little time was spent on comics as a media. Yet, I do think my students have a new appreciation for the genre. In the following weeks we read Junot Diaz’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the story of a Dominican-American comic book geek. Having recently read and enjoyed a comic book, students did not condemn Oscar for his reading habits, as has happened when I have previously taught this novel. They also favorably compared the cultural elements of Ms. Marvel with that of Oscar Wao, commenting on how both works use their characters’ love of super heroes to show how they are disenfranchised from and yet learn more about their cultures. Much time was spent on the meaning behind both Kamala and Oscar being New Jersey natives (underdogs) and on if Oscar would have been a Ms. Marvel fan (yes). I consider this a win for comics and unconventional heroes everywhere.

From an academic and social perspective, teaching Ms. Marvel was a success. The students accepted comics as a legitimate medium and Kamala as both a representation of the American dream and a fully-realized character who transcends such a simple label. However, as a class they were still disdainful of superheroes in general, dismissing them as “action movie fodder.” To deepen the discussion of these complex cultural icons, next semester I plan to pair Ms. Marvel with Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. I hope this novel, which focuses on two young Jewish men in the 1940 that create the superhero the Escapist as a way to fight Hitler, (an intentional parallel with Superman and Captain America, both of whom fought Nazis) will help students understand the cultural importance of our spandex clad heroes, both yesterday and today.