The phrase “walk a mile in someone else’s shoes” isn’t something that most people take literally, on their path to understanding the harsh realities of life that another person can face due to systematic oppression. Unfortunately, in November 1970, the creative team on Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane (writer Robert Kanigher, artist Werner Roth, and inker Vince Colletta) proved that they were literalists when it came to that sort of thing by giving us the story “I Am Curious (Black)!” in the 106th issue of the comic. “I Am Curious (Black)!” is one of those comic stories that you rarely hear about because it tells a different story than intended — and it really hasn’t aged well.

The phrase “walk a mile in someone else’s shoes” isn’t something that most people take literally, on their path to understanding the harsh realities of life that another person can face due to systematic oppression. Unfortunately, in November 1970, the creative team on Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane (writer Robert Kanigher, artist Werner Roth, and inker Vince Colletta) proved that they were literalists when it came to that sort of thing by giving us the story “I Am Curious (Black)!” in the 106th issue of the comic. “I Am Curious (Black)!” is one of those comic stories that you rarely hear about because it tells a different story than intended — and it really hasn’t aged well.

Being Black for a day isn’t long enough for anyone to understand the realities of Blackness in America. Not in 2016, and certainly not 45 years earlier when “I am Curious (Black)!” was originally released — just a scant handful of years after the Civil Rights Movement saw some of its greatest victories, and losses.

Despite the fact that the premise is definitely dated, it’s considered one of the most iconic Lois Lane comics in her canon. The story was even recently included in the 75th Anniversary book that DC put out to celebrate Lois Lane’s long history back in 2013. Which is kind of weird because, while it’s a gorgeously drawn issue, the message — basically the idea that racism happens equally to white and Black people; that in the end, we all bleed red, so actually talking about race and race relations doesn’t matter — isn’t exactly the sort of thing that you’d imagine a company like DC wanting to hold on to.

…the original comic was a misguided white savior narrative that focused more on Lois Lane being “black for a day” than on any actual critique of racism or a racist society

In a world where right now, film and television creators are more comfortable with the idea of centering white people (and whiteness) in narratives about race-based oppression while race-based oppression in the ‘real world’ climbs, the idea that “I Am Curious (Black)!” can be presented as a purely innocent and iconic book is a worrying one.

First, let’s talk about how the plot of “I Am Curious (Black)!” is relatively simple.

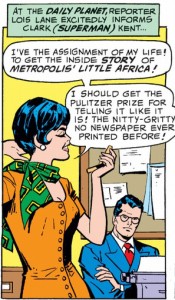

Lois Lane, our take-charge lady reporter, wants to get the inside scoop on the Metropolis neighborhood of Little Africa. Neighborhoods like Little Africa have (and still do) exist in the United States. The name is usually a colloquialism or nickname for an area like Alabama’s Africatown that has a large African and/or African American population. So while it seems a bit messed up that any writer would choose to name a neighborhood Little Africa, it’s actually a part of African American history. But these neighborhoods were also distanced from other, whiter neighborhoods. Residents lived with the knowledge that they were kind of kept apart from white residents due to zoning laws, unequal loan opportunities, and discrimination in the workplace.

Obviously the Metropolis that Lois lives in isn’t very diverse or welcoming to Black people, if they have to live in Little Africa, away from other citizens.

The reason Lois wants to do this expose is because she believes that such a story should garner her a Pulitzer Prize. As far as Lois knows, no one has ever written an in-depth expose about that community before. Lois and the text assume that no one has previously written about Little Africa. Despite the fact that there have been Black newspapers and Black journalists working in circulation since the nineteenth century, there’s never an inkling that that there were Black journalists that may have written about Little Africa.

The reason Lois wants to do this expose is because she believes that such a story should garner her a Pulitzer Prize. As far as Lois knows, no one has ever written an in-depth expose about that community before. Lois and the text assume that no one has previously written about Little Africa. Despite the fact that there have been Black newspapers and Black journalists working in circulation since the nineteenth century, there’s never an inkling that that there were Black journalists that may have written about Little Africa.

(Just like how the notion of Black characters being centered in what’s supposed to be a story about Blackness never seemed to have entered Robert Kanigher’s mind either.)

Instead of thinking that the Black people in Little Africa should tell their own stories, or that she should facilitate Black journalists getting awards for telling their own stories, Lois just dives right into Little Africa. No serious thought is encouraged on the issue.

From early on in her inception, Lois has been shown as a journalist of a very high caliber. She’s shown to be empathetic and full of integrity as she writes stories and interacts with sources in respectful and responsible ways. Lois was a character that did what was right even at the risk of her life.

So where’s that Lois in this story?

Lois Lane comes into Little Africa with the intent to collect a story. When going there as herself — not just as a reporter, but as a white one — doesn’t work, she puts on a costume of culture and identity to make herself more approachable. She throws aside her integrity and the core of her beliefs so that she can snag a story that might win her an award.

Only three things matter to Lois in “I Am Curious (Black)!”:

- Being successful in her career

- Her (largely nonexistent) romantic relationship with Superman

- Her reputation

Lois is absolutely not going into Little Africa because she actually cares that Metropolis is so segregated that Africans and African Americans are forced to live in a crumbling slum. She’s doing it because she wants to get an award that Black journalists would have had trouble gaining for writing a story about Little Africa themselves — something that we’ll talk about a little later.

When she goes into that part of the city, she’s insulted multiple times due to her race and the Black people in the neighborhood are openly mistrustful of her. Everywhere that she goes in Little Africa, her presence is met with suspicion and silence. A woman actually wheels her baby carriage away rather than let Lois touch her child.

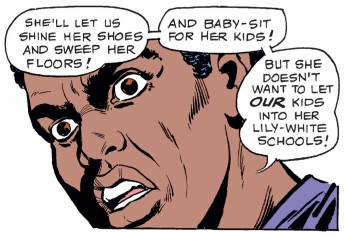

Dave Stevens, a young Black activist, actually points to Lois and calls her out for her presence in Little Africa while at a street meeting. He talks about how white women like Lois are fine with using Black people to clean their houses and watch their children, but not with them living nearby or having their children attend integrated schools.

Offended by her treatment, not understanding what she represents as a white woman wandering gaily into a neighborhood that most likely exists due to unspoken rules in Metropolis that force segregation, Lois doesn’t stop to think that she’s the wrong reporter for the job.

Instead, she decides that she absolutely must get her story by any means necessary. She asks for Superman’s permission to use the Plastimold — a Kryptonian body morphing machine mentioned in an earlier issue — to turn her into a Black woman.

Appropriation isn’t acceptable on any level, but to appropriate identity for the express purpose of writing an article or story when you could just support diverse voices telling their own stories?

The transformation will only last for a day, Superman tells Lois. But that should be plenty of time for Lois to get her scoop (and for the readers to get a feel-good story about togetherness). On her way back to Little Africa, Lois experiences her first taste of racism when a taxi driver that she’s friendly with zooms past her in order to pick up a white passenger. On the subway, she can’t get away from the feeling that the white people in the car with her are staring hatefully at her.

In the same way, Lois’ return to Little Africa is much different.

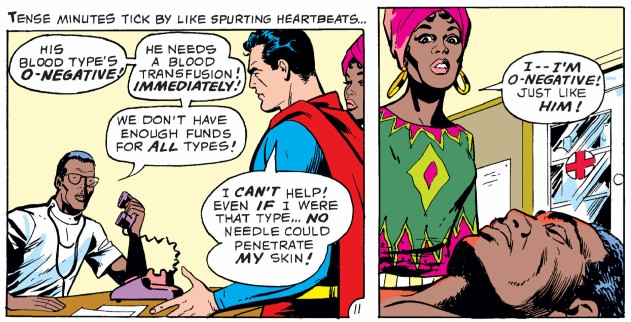

She’s privy to more things. She’s met with less hostility. A young mother even invites Lois up to her apartment after Lois helps her. Lois even makes a connection with Dave Stevens, the young man who had pointed her out as the “enemy” when she had been walking through the neighborhood earlier. His reaction to her absolutely changes and the way that he moves from being angry with her to wanting to protect and shelter her is notable. Because of this new connection, Lois is present when Dave gets shot trying to take down a duo of drug dealers.

White saviorism is harmful and negative trope which prioritises on whiteness as the central focus of interracial stories.

White saviorism is harmful and negative trope which prioritises on whiteness as the central focus of interracial stories. Whiteness saves characters of color from the enemy — or more typically, from themselves. The trope focuses on lifting societal whiteness, and white people, above the people they’re rescuing or saving. It hinges on the idea that people of color can’t or won’t save themselves and that white characters are the only ones that can make the world a better place.

Look at films like 2009’s Avatar or 2011’s The Help. These stories reinforce whiteness by putting forward the image of a “one true savior” who just happens to be white, as well as being the only person that could possibly help out the “less sophisticated” characters of color fight back against the hardships of and oppression in their lives. In Avatar, Jake Sully is the only person who can help the Na’vi fight back against colonizers from Earth in the distant future. In The Help, we see a white character decide to write a book about Black maids in the Civil Rights-Era South and wind up getting accolades for telling their stories. In The Last Samurai (2003), Tom Cruise’s character literally goes to Japan in order to become the last (and best) samurai.

White savior narratives, like the ones in those films, like the background noise of “I Am Curious (Black)!”, remove the focus from issues of racism, imperialism, and colonialism — central themes in the history of whiteness — in order to land on how there are “good” white people who are combatting oppression. White savior narratives silence people of color. They take the stories and experiences away from characters and people of color in order to make sure that the viewer focus and sympathy lands on whiteness and what white people are doing to inject themselves into the stories and lives of characters of color.

The narrative revolves around Lois. It centers on her experiences with racial discrimination in both her regular body and her Black body. When Lois observes the people who live in Little Africa, she does so in a way that makes you feel as if she wasn’t expecting their humanity or dignity.

There’s a set of pages in this comic that really shows that the creative team in charge of the comics didn’t have much experience themselves when it came to thinking about Black people as well…people. It’s really no small wonder that Lois is so bad at interacting with them either.

There’s a set of pages in this comic that really shows that the creative team in charge of the comics didn’t have much experience themselves when it came to thinking about Black people as well…people. It’s really no small wonder that Lois is so bad at interacting with them either.

Once Lois returns to Little Africa, she heads to a crumbling tenement where she puts out a fire in a trash pile and is promptly invited into the home of a woman who lives right across from the pile. The apartment where she and her children live is rat-infested and has plaster dropping down onto their heads. All in all, it’s far from an ideal situation, but the young woman still pauses to ask Lois if there’s anything she can do to help her. Thankfully, Lois’ teary response is an internal one as she thinks to herself: “She lives in misery… Yet asks if she can help me!”

Um…

Empathy exists.

People sometimes ask if they can help other people out because being kind is cool. It shouldn’t so surprising to Lois that people care about one another. I’ve mentioned before that I don’t think that Lois saw the residents of Little Africa as people and this cinches it for me. If you’re interacting with people that you don’t necessarily see as people, any occasion where they show empathy towards you — put themselves on your level, or see themselves as potentially benevolent towards you — is shocking.

I think that a major issue here is that the staff at DC couldn’t figure out how to handle nuanced portrayals of Black women. At this point, none of the three creators — men — working on “I Am Curious (Black)!” were in fact Black.

Their knowledge about Blackness was coming to them second hand at most and they definitely would have had preconceived notions about what Black people would be like. These aren’t just Lois’ reactions to Black people and the realities of Blackness. These are Kanigher’s reactions and his experiences informing his reflections. So moments like this, where Lois’ reactions are shockingly out of touch and also make her look bad as a character, are coming from a place and from people who (whether consciously or subconsciously) don’t understand that Black people are just as empathetic and intuitive, as dimensional, as anyone else.

In “The Case of the Disappearing Black Detective Novel,” writer Sarah Weinman shares a quote from black mystery writer Hughes Allison where he talks about the ways that white writers failed when trying to write Black characters:

“You can’t guess. You have to know. You have to know Negro life as Negroes live it—and they live on numerous political, economic, social, and intellectual levels growing out of cause-and-effect patterns, the character of which is historical. The history of this matter is well documented—so well documented that those who are informed can tell at a glance who knows and who is guessing.”

The entire article is a must read for writers but Allison’s quote really is something that writers need to hold close when attempting to write Black characters.

There are centuries of a truly horrible history behind African Americans and all of it laid out for researchers to discover. You can’t write about Black characters (even in contemporary stories) without being aware of what we and our ancestors went through during slavery and the Civil Rights era because it informed the way that we exist as people today. That’s another reason why the message of togetherness in “I Am Curious (Black)!” falls flat. It is incredibly obvious that despite the creator’s intent, no significant thought was put into actually addressing the history of racism that the African American residents of Little Africa have behind them and what they have to live with.

And in “I Am Curious (Black)!” there are several instances of white saviorism. There’s the initial event with Lois deciding that she — rather than Black journalists working for Black newspapers — is the best person to dive into the neighborhood of Little Africa in order to write a hard-hitting article.

Next, we see it in her desire to return to Little Africa after her initial efforts to collect sources end poorly. Lois has to find out the truth and she has to tell the story of the Black residents of this community even if it means hiding her real race.

Lastly, Lois literally saves Dave Stevens’ life, because his community doesn’t contain the blood type which matches his. It’s the ultimate white savior moment in the comic, and once Lois does her good deed and saves Dave, she returns to her regular skin tone. Lois’s Black experience is framed as morally generous. Within this part of the narrative, Lois is being held up as a nearly saintlike figure, interacting with the poor and disenfranchised Black people in the neighborhood because she’s just such a wonderful person for coming down to Little Africa.

Instead of a conversation about the inequalities that lead to the hospital for Black people in Metropolis’ Little Africa being deprived of blood for all types due to racism, we get her white savior coup de grace.

While they wait for Dave to feel steadier, Lois confronts Superman about their relationship (or lack of it) in a way that that really should have been left out of the story — or placed at a different point, so it could have been longer. Because this is an issue of Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane, the question of when or if Lois and Superman will ever tie the knot remains unanswered. Much of the series revolves around Lois being rejected or Superman going out of his way to confuse her or make excuses as to why he can’t marry her. In I Am Curious (Black), this comes even at the expense of the attempt at a politicised plot.

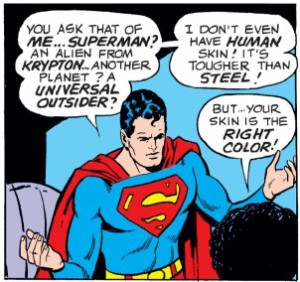

At the start of the issue, there was a panel where Lois asked Superman if he’d still marry her if she stayed Black. We get the answer to that question at the end of the issue, and it’s not much of an answer. Superman essentially refuses to answer the question, firing back at Lois with:

“You ask that of me… Superman? An alien from Krypton? A universal outsider?”

Lo is does point out that even if his skin is inhumanly tough, it’s still the right color. He’s still seen as white. It’s true. Superman benefits from white privilege, despite not actually being human.

is does point out that even if his skin is inhumanly tough, it’s still the right color. He’s still seen as white. It’s true. Superman benefits from white privilege, despite not actually being human.

He’s lived almost all of his life as a white man and he’s received privileges because of it. Metropolis is accepting of Superman’s alien nature because he appears to be a white man and therefore, his inhumanity is brushed under the rug.

Meanwhile, actual Black people in Metropolis are cloistered in Little Africa away from the rest of the city because their humanity is up for question in a way that Superman’s never would be.

So we center whiteness once more. Superman is divorced from race while he benefits from whiteness. He’s inhuman enough that he can respond to Lois’ question in a way that makes her look bad, but he’s still actively benefiting from the way that he appears to be a white male in day to day procedures. Superman may be an alien, but he benefits from white and male privilege in every aspect of his life.

Superman may be an alien, but he benefits from white and male privilege in every aspect of his life.

Any hope that the reader has for actual commentary about race in this story vanishes underneath the endlessly rehashed conversation about why Superman won’t marry Lois Lane (answer? because he has enemies that would kill her). We had a moment where Kanigher could have actually used the comic to discuss interracial relationships and race, only for it to fall by the wayside.

Before Lois can say another word, she returns to her normal body.

Seriously, Lois returns to her normal body before the story ends (and well before 24 hours have passed). At most, she’s Black for 12 hours, not 24.

At the end of the issue, we’re supposed to feel super warm and fuzzy. Lois and Dave seem to have moved past race, because we all are people who bleed red. It’s a story about race in comics that doesn’t talk about how racism affects people of color. It missed the mark during the period that it was written and the fact that it was republished, unedited, over forty years later doesn’t fix thing. 1970 is when this comic came out. Let’s look briefly at some history revolving around Black Americans in the United States at this time:

- In August of 1965, Congress passes The Voting Rights Act in direct response to the Selma to Montgomery March earlier that year.

- In June of 1967, the Supreme Court rules that banning interracial marriage is unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia.

- In April of 1968, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by a white supremacist. Shortly afterwards, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was passed by then-President Lyndon B Johnson.

In 1970, Black people living, loving, and working in the United States had only recently received government support of their rights to be treated as human beings. The grandparents and parents of people who are alive today had to fight for the right to eat where they wanted, vote without being harassed, and marry the person that they loved. And that was within five years of “I Am Curious (Black)!” being put out by DC Comics.

There is an inherent selfishness in the narrative of “I Am Curious (Black)!” that stems from the idea that anyone can learn what it feels like to be weighed down by centuries of systematic oppression after wearing someone else’s skin for less than a day.

The Black people in Little Africa exist to Lois in very narrow fields. They’re distrustful when she’s white, welcoming when she’s not, and in the end, we’re shown that both she and Dave Stevens (who most assuredly had experience with racism in his daily life) learned this oh-so valuable lesson about equality.

That’s really what we’re supposed to learn from “I Am Curious (Black)!”, the erroneous assumption that racism is something that can happen to white people and that Dave Stevens is just as prejudiced as Lois Lane was before costuming herself with Blackness.

The intentions behind the comic, to celebrate togetherness and show that we all matter because of our differences as people, don’t negate the fact that it’s incredibly tone-deaf and comes packed with selfish motivation to boot. “I Am Curious (Black)!” looks at the idea of oppression as something that can be understood by taking on an identity as a costume, and that’s never going to be okay.