Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-Kun Vol. 1

Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-Kun Vol. 1

Izumi Tsubaki (C)

Publisher: Yen Press

Release Date: November 17, 2015

Disclaimer: This advance copy has been supplied by the publisher

What makes pop culture amazing is its ability to act as a mirror. Not just the kind that reflects what you’re already expecting to see but one that also reveals things about you that you weren’t aware of. Of course, I don’t mean the surprise pimple on your chin but the ideas that you hold inside yourself, whether it’s about the homeless, race, sex etc. For me, Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-Kun Vol 1, by Izumi Tsubaki, got me to think about my relationship with violence in the media and specifically, in comedy.

Overall, the comic was fantastic. I definitely intend on reading more. But something was nagging at me after putting it down. Let’s set the scene.

The story is about high schooler, Chiyo Sakura, who decides to finally tell her crush and classmate, Umetarou Nozaki, how she really feels. Due to a misunderstanding, she gets hired as his assistant instead to help him with the manga he publishes. The series is essentially about this experience as they meet various people who either inspire characters in Nozaki’s manga or are helping him create it. One of those inspirations is Yuu Kashima.

Along with the new English translated manga that was recently released, there’s also an anime adaptation that debuted this past July. I’ll be using the images from that to point to examples and moments in the comic.

Along with the new English translated manga that was recently released, there’s also an anime adaptation that debuted this past July. I’ll be using the images from that to point to examples and moments in the comic.

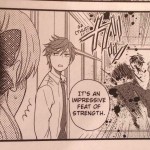

Kashima is introduced to Nozaki and Sakura as “The Prince of The School” and they automatically assume they’ll be meeting a guy. They discover that Kashima is a girl, identified by herself and others as a girl, but is drawn in the manga as androgynous and embodies qualities stereotypically attributed to male identifying individuals. She flirts with girls disruptively to the point that she is constantly late for the drama club, where she plays those princely roles, and requires an escort by the drama president himself to get there on time. Sakura, of course, imagines the escort to be something like this:

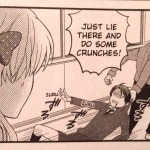

In reality, it’s something like this:

Hori, the drama club president, forces Kashima to go to drama club through violence. It’s framed as comedic. Comedy violence, especially animated and illustrated comedy violence (which by definition is detached from “reality”) tends to lack consequence. Wile E. Coyote blows up after a failed attempt to catch the Road Runner but just has a few scratches. Those scratches disappear in the next scene. Repeat. Even with live action slapstick comedies like The Three Stooges, violence in the context of comedy is momentary. It’s here, and then it’s gone for the next joke to be set up.

When I was confronted with this in the manga, somehow it felt wrong. What really surprised me was why I thought it was wrong. Kashima is a girl –“comedy” where a male character is violent towards a female character doesn’t sit well with me. Then I questioned that thought proess with, “Is Kashima a girl who assumes the role of a guy?” because in my head, comedic violence between men made sense. Predatory masculine violence against women is rampant in real life, and seeing that dynamic reproduced in fiction is disturbing. Not because of the stereotypical “women are weak and need to be protected;” there are imbalances in our society — socially and institutionally — that allow for women to be dispropotionately assaulted physically. Depictions of this in media as a norm is dangerous in a society that already treats it as such.

However, men also suffer violence. They suffer domestic violence, violence if they’re trans, violence if they’re black or gay. So I started to stray away from the role of gender in comedic violence and began to look at the use of comedic violence itself. Like I said, it seems to work because of the temporary aspect, and the lack of consequence. You don’t actually see blood — the association of blood to violence makes it all very real. When blood is involved, the consequences of violence are literally oozing out; that’s why very violent movies can get away with a PG-13 rating as long as blood isn’t shown. In the manga, upon first reading, I didn’t notice the blood. It was while I was watching the anime that I noticed it in all of its red glory and looked back to see that yes, there was also blood in the manga. This blood was black since the book is published in black and white.

Blood takes this comedy violence from questionable giggles to “uh, this is uncomfortable.” However, it doesn’t stop there!

Kashima becomes jealous of Hori’s friendship with Nozaki — which is based on their working relationship on the manga, but she doesn’t know this (it’s a secret kept from people who aren’t helping Nozaki create the manga). One by one, she lists the examples that prove Hori likes her best and one by one, Sakura shuts them down. Finally, as shown in the above image, she settles on the fact that he hits her as an example of his affections for her (platonically, of course). Thankfully, Sakura shuts that down as well but it’s scary to think that Kashima is linking friendship or love to physical abuse. It takes a questionable gag to a place that’s no longer funny at all.

So is comedic violence funny? Would I or you be wrong in laughing at it if it appeared in our comics or television screens, even if it was done “the right way”? I grew up watching violence at a young age whether it was The Bugs Bunny and Tweety Show, the Justice League animated show, or Blade Trinity in middle school. My parents, like many, were more concerned about my exposure to sex than whether or not I saw someone get decapitated, and would only turn me away from violence if it intersected with sex or if there was too much swearing. Having said that, my parents made sure that we understood that violence should only be used in self defense. If we were instigators of violence, there would be consequences which ran counter to what I was seeing on TV, and it’s because of this that I was able to have a conversation with myself on what I was seeing in this manga.

Even if it were a viable suggestion, I don’t think eradicting all violence from our content is the answer. People are free to say no to violence in their media just like other people can enjoy it in theirs. I do think it’s important to have a conversation with your kids, loved ones, friends, etc, about what you’re viewing/reading and to interrogate why you do (or don’t) like the things you’re devouring. I’ll continue to read this manga because I had a fun time. These troublesome Kashima bits were minor, stacked against the overall story. I will, however, still keep an eye on Kashima, and continue to challenge my views on violence.