SPOILER WARNING: This essay contains spoilers pertaining to Inio Asano’s Solanin

The western world is riddled with narratives about women posing as men to enter male-dominated spaces. In Just One of the Guys (1985), the protagonist Terry, a beautiful, popular high school girl, disguises herself as a boy so that she can be taken seriously as a journalist and win an internship usually reserved for male students. She’s the Man (2006) is centered on Viola, an aspiring soccer player who enrolls in an all-boys’ boarding school when her own school drops its girls’ soccer team. Another Viola—Viola de Lesseps—in Shakespeare in Love (1998) longs to be an actress, but since the law forbids women from working in Elizabethan theatre, she invents a male persona Thomas Kent and lands a job working for Shakespeare. Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novel Monstrous Regiment (2003) revolves around Polly Perks’s search for her brother, a soldier missing in action. Despite women being banned from the army, Polly transforms herself into a male soldier to find her less qualified sibling. Disney’s Mulan (1998), though based on a Chinese narrative, is also rooted in western thinking in that it is a Disney feature film. Mulan becomes a male soldier so that her old and sickly veteran father doesn’t have to fight in another war.

According to Sarah Kornfield’s essay, “Cross-cultural Cross-dressing: Japanese Graphic Novels Perform Gender in U.S,” most western gender-benders follow a specific narrative pattern:

- In order to achieve a goal, a woman must enter a traditionally male space.

- Perceptions of her sex prevent her from participating.

- Thus, she disguises herself as a male and is accepted, albeit clumsily, into the male space.

- Initially, she struggles to adapt to the exotic and mysterious environment of men.

- Her male friends and peers eventually accept her as a worthy man. Sometimes, the most competent one falls in love with her.

- Her sex is discovered, and she is punished.

- She finds a way to redeem herself.

- Her comrades forgive her for her transgression and accept her for who she is…supposedly. And if applicable, her manly, obviously heterosexual love interest embraces her as his girlfriend.

- The female protagonist returns to living as a woman; her “true” sex [1].

- These women are not dressing as men for the fun of it. Gender-bending is an act that is purposeful and always condemnable.

Conversely, Japanese narratives in animation and comics support a different perspective on the cross-dressing woman. In Bisco Hatori’s Ouran High School Host Club (2002-2010), Haruhi attends an elite and expensive school with a sex-based dress code. However, she dresses as a boy without purpose or penalty, and her peers would often mistake her for one. After breaking an expensive vase belonging to an all-boys’ host club, she must become one of their members in order to pay her debt. That she dresses as a boy is merely a convenience. Haruhi is not dressing as a boy solely to fit into the club. Her appearance in male attire is a form of gender expression.

In Naoko Takeuchi’s Sailor Moon, Haruka Tenoh, though we see her blasting yoma in a short skirt and heels, prefers to dress in the male school uniform for no reason other than to express her identity as a woman. Additionally, Emura’s W Juliet (1997-2002) stars a boisterous, cross-dressing female protagonist. Most famously perhaps is Utena Tenjou of Chiho Saito’s Revolutionary Girl Utena (1996-1997). Seeking the noble prince she met as a child, Utena dons a boy’s school uniform (albeit with sexy short-shorts) to become her own prince. The act of being a prince isn’t merely to embark on this journey. It is part of her lifestyle and identity.

Unlike the narratives of the West, Utena is never punished for dressing as a boy. It’s no secret that she is female, and, despite her gender-bending lifestyle, the boys at her school deeply admire her. She has pink hair, a slender, elegant physique, and dreamy eyes–qualities associated with traditional depictions of shojo manga protagonists. But Utena is also valiant and quite ballsy. She has mad fencing skills, a calm demeanor, and an unmoving sense of duty and purpose–qualities often reserved for male love interests. Unlike the girls of Boys Over Flowers, High School Debut, and Ranma ½, who become increasingly weaker and more dependent on the men in their lives, Utena’s strength develops, her path to being a prince becomes clearer, and she never sells out her power for love. Her power is love.

These women go unscathed by puritanical social mores surrounding gender. At the end of Ouran Host Club, Haruhi reveals the truth about her sex to her friends, but they had already known she had been a female all along and are rather, less concerned with her emergence as a “true” female and more concerned with who she is–a studious, compassionate, and beautiful young woman as well as a resourceful, composed, and popular male host. While Haruka’s friends initially mistook her for a boy, they were no less drawn to her when they discovered she was a female student at a prestigious school. They continued to fawn over her, even going so far as to support her at one of her motocross competitions. And Utena seems to be admired because she is a gender-bender–unique, original, untethered by the gender binary.

While the west doesn’t seem capable of fully processing the numerous reasons as to why a woman might cross-dress (because why wouldn’t a woman want to be a man, the greatest thing ever?), Japanese manga explores gender expression in ways that are authentic and truthful. Nonetheless, much of these manga belong to the shojo category which has a tendency to stick to stock narratives pertaining to love and romance.

Few manga, however, have examined gender-bending in the way that Inio Asano’s Solanin (2008) has.

Meiko Inoue is a twenty-something-year-old office lady—depressed and in a relationship with a flighty illustrator named Taneda. As they begin to reject their society’s need for mundanity and certainty, Meiko quits her job, while Taneda decides to pursue his goal to become a full-time musician in a band. When Taneda is killed in a traffic accident, Meiko becomes even more aimless. She drifts from day to day without purpose; then, following a conversation with Taneda’s father, she discovers her new role: “to prove that Taneda existed [2].” Meiko picks up Taneda’s guitar and learns to play despite having previously displayed only a minimal interest in music. She joins the band, and they play Taneda’s song entitled “Solanin” at a major venue.

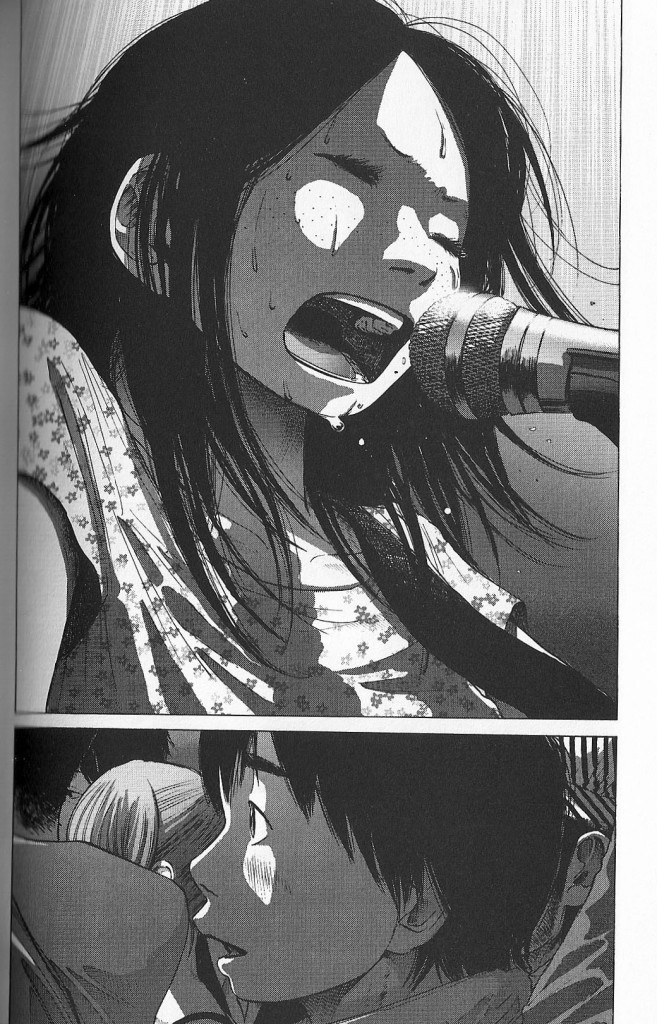

No, Meiko does not literally dress as a boy. She does not wear Taneda’s clothes or adopt Taneda’s boyish disposition. She does not cut her hair or wear his glasses, but, in the climactic scene, Meiko and Taneda are one. The latter exists within Meiko as she drops to her knees, guitar in her rapidly moving hands. She proves his existence by living as he did for just a few, brief moments on the stage.

The artist visually expresses this connection several times throughout the story. For example, when Meiko first plucks the string of Taneda’s guitar, the next frame shows the other band members’ shocked faces, for they see, not Meiko, but Taneda. They rid themselves of this vision by claiming that the ringing sound mimicked that of Taneda’s because it was on his usual amp setting by coincidence. Their skepticism is gone, and they decide to let Meiko join the band, perhaps in hopes of hearing a remnant of Taneda’s sound once again.

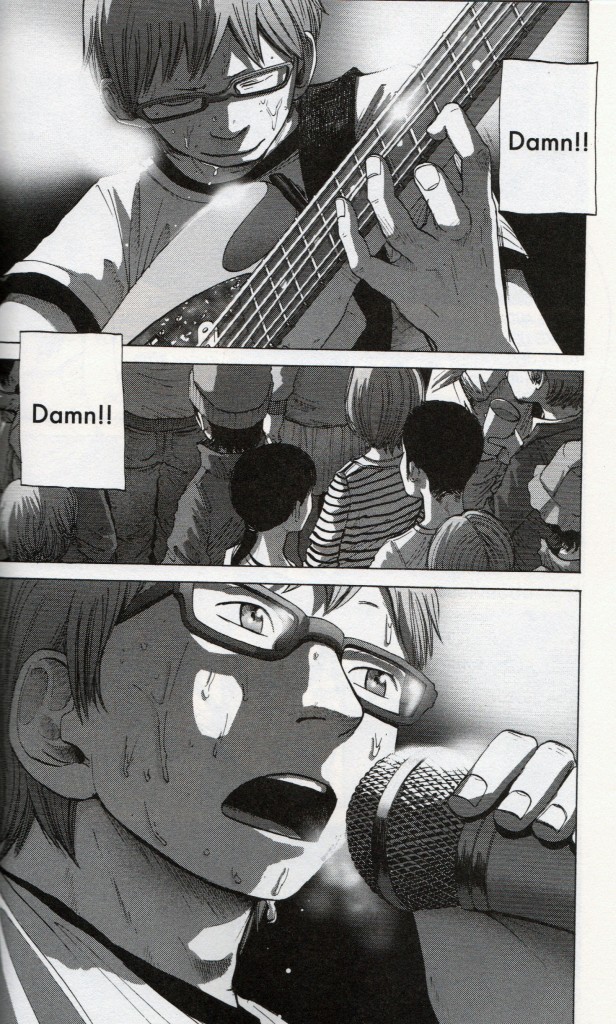

Meiko’s adoption of Taneda’s spirit and existence is also indicated by the visual linking of the past and present. Seconds before his accident, Taneda experiences a flashback of playing with his band, surrounded by people cheering, dancing, and singing. He is shown playing his guitar with all his heart and soul, sweat dripping down his face, his fist in the air, illuminated by intensely bright stage lights. Meiko is in the crowd, watching and mystified. During the climax, similar shots of Meiko dominate the pages in a dramatic sequence as she plays Taneda’s final song, his last performance with his band. Meiko takes on her role as Taneda for the purpose of proving his existence.

Gender-bending is often perceived as a literal form of expression or an act of defiance or purpose. A woman dresses as a man to accomplish a feat; a young girl lives as a boy to explore her identity and sexuality; a woman fluidly moves from one gender to another because she does not see the binary that others live by. But in the case of Solanin, Meiko does not just gender-bend. She transcends gender, acknowledging her spiritual unity with Taneda. Her taking on Taneda’s role does not revolve around his gender, but on his innermost being, the part of humanity that is unlimited by perceptions of biological sex and gender. In Solanin, gender-bending isn’t a transgression, but an opportunity for spiritual development.

Gender-bending is often perceived as a literal form of expression or an act of defiance or purpose. A woman dresses as a man to accomplish a feat; a young girl lives as a boy to explore her identity and sexuality; a woman fluidly moves from one gender to another because she does not see the binary that others live by. But in the case of Solanin, Meiko does not just gender-bend. She transcends gender, acknowledging her spiritual unity with Taneda. Her taking on Taneda’s role does not revolve around his gender, but on his innermost being, the part of humanity that is unlimited by perceptions of biological sex and gender. In Solanin, gender-bending isn’t a transgression, but an opportunity for spiritual development.

References

[1] Kornfield, Sarah, “Cross-cultural Cross-dressing: Japanese Graphic Novels Perform Gender in U.S.,” Critical Studies in Media Communications 28.3 (August 2011), 224. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15295036.2011.553725?journalCode=rcsm20#preview

[2] Asano, Inio, Solanin, Viz Media (January 2008), 269. http://www.amazon.com/Solanin-Inio-Asano/dp/1421523213/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1411839100&sr=1-1&keywords=solanin

Excellent analysis!